This season of films is presented in collaboration with Cinema Reborn, the Istituto Italiano di Cultura, Sydney, and the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities. For tickets CLICK HEREIntroduction by Associate Professor Jane Mills, UNSW

I acknowledge the Bidgigal people of the Eora nation, the traditional owners of the land on which the Ritz Cinema is on and pay by respects to their Elders, past, present and emerging. Their lands were never ceded. Always was, always will be, Aboriginal land.

On a personal note, my thanks to Blythe Worthy who worked with me to wrangle the speakers.

Lina Wertmüller’s films were hugely popular in the 1970s. Especially in America although also in Italy where her ‘commedia all’italiana, a film comedy style deriving its name from the title of Pietro Germi's film, Divorzio all'italiana (Divorce Italian Style, 1961), gave her a big following.

In 1975, she was the first woman ever nominated for an Oscar for best director for her film Seven Beauties.And then “pouf!” She seemed to disappear although, in fact, she continued making films until 2014.

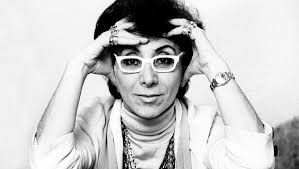

Wertmüller re-emerged triumphantly in 2019 when – at last - she was awarded an honorary Oscar (below). At the ceremony, at which Greta Gerwig and Jane Campion declared they were huge fans, rather than humbly thanking the Academy, Wertmüller boldly reprimanded it for its sexism , insisting that Oscar should be renamed Anna. How very Wertmüller!

A brief portrait.

She was born in Rome to a devoutly Catholic middle class family. Her full name, incidentally, is Arcangela Felice Assunta Wertmüller von Elgg Spañol von Braueich. This might explain Wertmüller’s penchant for absurdly long film titles: she once made it into the Guinness Book of Records for a film’s longest title. But as she said: "It is not so terrible to be ridiculous - I am living proof of this point!"

Her provocative, rebellious character made itself apparent early: as a teenager, she was expelled from at least 11 schools, the last for challenging Christian dogma that she objected to being taught as “the Truth.”. Doubtless, the nuns didn't much like her teenage passion for comic books, especially the Flash Gordon comic strip. She later cited this as an influence, explaining she found the framing “rather cinematic, more cinematic than most films.” (We'll see a character in this afternoon’s film, I basilischi, reading a Flash Gordon comic.) Upon leaving school at 17, she began working in the theatre and directing avant-garde puppet theatre – two more influences that can be seen in several of her films.

Wertmüller was like her films: over-the-top, in-your-face, emotional (often exhaustingly so), provocative and defiantly incorrect long before the term “politically correct” had been invented. She and her films were also perverse, funny and political. However, not everyone got or enjoyed her jokes: her satirical approach to gender and class politics often angered feminists and Marxists. Leaving the Communist Party in 1959 and becoming an ardent, although never uncritical, socialist, Wertmüller was a socialist-feminist who could take a joke. She could dish them out too.There was probably no nose she didn't enjoy getting up. And no-one of any political persuasion she didn't enjoy sticking up her middle finger at. Which might make her and her films sound rather vulgar. As, gloriously, they often were.

Films in this retrospective

|

| I Basilischi/The Lizards |

Wertmüller’s film career didn't start exactly by chance. Although she did have the good fortune to have a girl friend whose husband happened to be Marcello Mastroianni. Who, of course, knew Fellini. What do you do if you want to learn how to make films? If you're Lina Wertmuller, you don't hang around hoping to get a job as a tea-maker or, if you're really lucky, a runner. You knock on Fellini’s door and demand to be his Assistant Director. She got the job on 8 ½ (1963). This led to her first film I Basilischi which she made in the same year. Before introducing this film that we’re seeing today, let me briefly outline the films and speakers in store for us over the next six Sundays.

|

| The Seduction of Mimi |

On Sunday 4 April,in The Seduction of Mimi (Mimi’ metallurgico ferito nell’onore1972) you’ll meet the devilishly handsome Giancarlo Giannini (who I think of as Wertmuller’s muse) playing a Sicilian dockworker fighting Mafia corruption and the wiles of a beautiful young Communist organiser - with lack of success in both cases. This ferocious farce that won Wertmuller best-director award at Cannes will be introduced by Dr Blythe Worthy,researcher and adjunct academic at the University of Sydney and Film Reviews Editor for the Australian Journal of American Studies.

|

| Love and Anarchy |

On Sunday 11 April,we have Love and Anarchy (long title coming up: Film d'amore e d'anarchia, ovvero: stamattina alle 10, in via dei Fiori, nella nota casa di tolleranza…1973). Set in fascist Italy just before the outbreak of World War II, Giannini plays a farmer turned anarchist who stays in a brothel while planning to kill Mussolini and, inevitably, falls in love with one of the whores. As you do - if, that is, you’re in a Wertmüller satire. It will be introduced by Associate Professor Bruce Isaacswho teaches Film Studies at the University of Sydney; read his ‘Great Movie Scenes’ column in The Conversation https://theconversation.com/au/topics/the-great-movie-scenes-61548). I confess I asked Bruce – also another male colleague – partly because I wanted their response to what has been described at times as Wertmüller’s man-hating, knee-jerk feminism.

|

| All Screwed Up |

Next, on Sunday Sunday 18 April, ABC Radio entertainment reporter/ producer and critic specialising in music, film and TV Danielle McGrane introduces All Screwed Up (Tutto a posto e niente in ordine, 1974). In this, a group of immigrants try to adjust to city life but quickly find that everything is in its place, but nothing is in order. Rape, unwanted pregnancy, prostitution, poverty, and gender politics are all subject to Wertmüller’s own anarchic sense of humour: “Man(kind) in disorder” is a theme that Wertmüller has often said sums up her films. One of the reasons I asked Danielle is because I’m fascinated to know what a younger feminist today thinks of Wertmüller’s provocative brand of feminism.

|

| Swept Away |

On Sunday 25 April, Swept Away (Travolti da un insolito destino nell'azzurro mare d'agosto, 1974) will be introduced by Associate Professor Francesco Borghesi who chairs the Department of Italian Studies, University of Sydney and whose teaching includes “Passions in Italian Culture.” This film gives us a mischievous contest of wills between a beautiful, rich, bourgeois woman and a smelly (according to her) communist sailor (who find themselves shipwrecked on a deserted beach. One of Wertmüller’s better known films in Australia, it has stunning performances from the two leads, Giannini again (in a Cannes Festival Best Actor award winning role) and also the delicious Mariangela Melato.

|

| Seven Beauties |

The last two films of this retrospective on the first two Sundays in May areboth introduced by Associate Professor Giorgia Alù who teaches Italian Studies at the University of Sydney and whose research interests include Italian cultural history and visual studies. On Sunday 2 May, there is Seven Beauties (Pasqualino, Settebellezze, 1975), the film for which Wertmüller was nominated for an Oscar and Giannini was nominated for best actor. This is undoubtedly her most outrageous film. Most audiences find it confronting: when Wertmuller decides to explore not only gender and class but also the sexual politics of a Nazi concentration camp … words fail me…but they didn't fail Wertmüller, that’s for sure!

|

| Ciao Professore |

On Sunday Sunday 9 May, Giorgia farewells Wertmüller with her last film, Ciao, Professore! (1992). Critic Roger Ebert called this film about a strict teacher and his (much smarter) young students “a sweet movie.” But Wertmuller doesn't hesitate to expose the Italian political system which fails to address (let alone redress) the imbalance between wealthy northern Italy and poverty-stricken south.

So that’s the season. Leaving me with just a a small space in which to introduce her very first film:

I BASILISCHI ( The Lizards, 1963)

I’ll start by saying something about some members of her crew which would be any debut director’s dream. Actually, any experienced director’s dream too.

Cinematographer Gianni Di Venanzo shot Fellini’s 8½ and Juliet of the Spirits, and several films for Antonioni – including, incidentally, Antonioni’s Le Amiche (The Girlfriends, 1955) which screens at the Ritz on Friday 30 April at 6:30 in Cinema Reborn’s festival of restored films over the last weekend in April, see https://cinemareborn.org.au/2021-Program

The editor was Ruggero Mastroianni, Marcello’s younger brother, a prolific editor with 189 films to his credit including Fellini’s Amarcord,Juliet of the Spirits and Ginger and Fred.

Music:this was an early film of a little-known composer who the following year wrote the music forA Fistful of Dollars: Ennio Morricone! (The Morricone whistle starts here!)

The title.I believe the title has been poorly translated as The Lizards and lazily compared (sometimes unfavourably) to Fellini’s Vitelloni(1953). It’s true that both films portray a small group of aimless young men who loaf around in a rural Italian town all day, eyeing the young women and achieving nothing. But whereas vitellonitranslates as “calves” and Fellini portrays rather lovable, even frolicsome young bulls, Wertmüller deliberately calls her film basilischi meaning ‘basilisks’ rather than lucertola meaning ‘lizards’: a basilisk is a legendary deadly poisonous serpent. There is a sharper political edge to how Wertmüller depicts her young men: she shows that the poisonous ineffectual lethargy has seeped into their souls from the societal, cultural and political order from which they cannot escape. The people in her sleepy southern town (Fellini’s film was shot in central Italy) simply don't have what it takes to challenge a society that encourages them to take a pride in “putting up with their lot.” As the commentary – the detached voice of the place – puts it: “their history and surroundings makes them so.” Wertmüller captures the devastating effects of the economic imbalance between the wealthy north and the poverty-stricken south in ways that Fellini doesn't.

Critics love pointing out the influences on directors and in Wertmuller’s case, Fellini, neorealism and Pietro Germi’s comedy Italian-style are often cited. Fellini was undoubtedly an influence. Describing him, Wertmüller once said: “Meeting Fellini is like discovering a wonderful unknown panorama. He opened my mind when he said something that I will never forget: 'If you are not a good storyteller, all the techniques in the world will never save you.'”

And certainly, her films display a strong love for her locations – prosperous northern cities and also the poor southern villages and countryside – and at time, a neorealist documentary style. You’d be forgiven for thinking I basilischi’s wonderful opening sequence as the camera slowly pans round the ritual of family lunch followed by a siesta was pure documentary. But elements of stage theatre and comedy are too strong in this and i all her films for her to be considered a neorealist. As for comedy, this was one of her great strengths – it may also explain why she fell out of favour as comedy is notoriously subject to time and place.

I’ll end by sharing my favourite sequence in I basilischi, one that I think combines realism, location, sly comedy and something of the tone of puppet theatre. When Francesco (one of the basilisks) is making furtive advances on a young woman, we see her parading through the town streets, her bottom swaying – provocatively, it must be said - this way and that (she’s too bony to be jello on springs - but she’s trying), the pleats in her skirt swinging - alluringly - in and out, and her high heels going click, click click. For me it’s – I was going to say: “pure Jacques Tati”. Actually, it’s pure Wertmüller.

Enjoy the film!

Jane Mills.

This is an extended version of her introduction to the Lina Wertmüller retrospective at the Ritz, Cinema, NSW on 28 March 2021.