The sociological interest to be found in earlier Godard films such as Vivre sa vie and Une Femme Mariée (1964), in Masculin-Féminin “becomes the voice of revolutionary politics through the voice of the political activist” ( Wood 221 ed. Lyon). The activist becomes dominant following the suicide of the other young male protagonist (played by Leaud) who had been seeking fulfilment through personal relationships. Eventually, in each of the Dziga Vertov Group films, the voice of revolutionary politics becomes the film's own voice.

La Chinoise (1967) was commonly perceived, on its release, as a caricature, not a representation of an ultra - left Maoist group, at times ironically infantile in the dangerous excess of their plans to use the terrorism of the Chinese cultural revolution to create similar upheaval in the West. Such perception ignores Godard's dominant refrain for La Chinoise that “art is not the reflection of reality but the reality of the reflection.”

James MacBean warns that, given “Godard's taste for contradiction” and “ability to achieve a dynamic balance amid seeming oppositions,” it is a mistake to reduce La Chinoise to a single category such as “hilarious spoof, or dead-serious militance, insouciance or hard-line propaganda, aesthetic dilettantism or didactic non-art” (21). By Weekend (1968) the take on capitalism is angry, as MacBean puts it, “pushing the cinema of spectacle to the limit” as “civilisation devours itself,” the final image announcing “the end of cinema.”

With La Chinoise and Weekend Godard was still engaged in making films for commercial screening. After May 68 this all changed as he “turned his back on the bourgeois audience,” instead making films on 16mm for television and militant audiences.

|

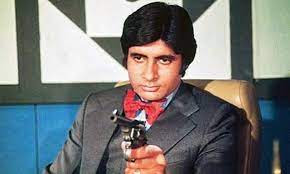

| Juliet Berto, Jean-Pierre Leaud, Le Gai Savoir |

Le Gai Savoir (1969)

Geoffrey Nowell-Smith sees the legacy in Godard's work in this turbulent period, 1968-71, as basically to be found in two films. One is Le Gai Savoir/The Joy of Learning (1969), commissioned by French TV – but never televised, seen only by political groups and film societies.

Godard's first break with the established means of film distribution and exhibition via the deconstruction of narrative, seeks a return to cinema’s ‘degree zero’. This he does in Le Gai Savoir making demands on the viewer by stripping away the conventions in the relations between image and sound described by Nowell-Smith as “intellectually ferocious” which “thirty years later continues to amaze” (ibid 195). Tony Rayns in ‘Time Out’ saw it as “a confused, idiosyncratic attempt at an analysis of the way things are, not yet a committed attempt to construct the way they should be.”

This first film marking Godard’s radical break from fictional concerns is ostensibly an adaptation of Rousseau's Emile, a classic of education theory, in its original form a fictional account of how a child is educated by being allowed to develop her own interests and thoughts rather than having to follow a rigid pre-ordained pattern.

Two students, Emile Rousseau (Jean-Pierre Léaud) and Patricia Lumumba (Juliette Berto) undertake a three-stage ('three year') course of study filmed with a single light source in the otherwise black void of an abandoned television studio. First by collecting collages of pre-existing words and images then criticising them before finally constructing models to discuss the relations between image and sound, ideology and politics, for it is frequently this combination that is most powerful in communicating ideology. Godard is obliged to question the role of cinema in this dialogue, issuing a manifesto in which he demands that directors worldwide create films that challenge and provoke.

|

| Gian-Maria Volonte (r), Wind from the East |

Counter cinema and after : Wind from the East (1970) , Tout va bien (1972)

The other film in which Nowell-Smith finds the legacy of Godard's work in the Dziga-Vertov period is Vent d'est/ Wind from the East (1970), one of seven completed films ranging from 50 mins to feature length, beginning with Un film comme les autres/A Film Like All the Others (1968) and ending with Vladimir et Rosa (1971). Five of these, including Vent d’est , were directed in name by the Dziga-Vertov Group (DVG) but in practice, for the most part, by Godard in collaboration with Jean-Pierre Gorin, an informed and engaged cinephile and Maoist, although more fellow traveller than activist. Godard insisted that auteurism be subsumed by the socialist collective. The expectation for the DVG films was as forerunners of a counter-cinema, “an open-ended polyphonic form,” as proposed in a seminal essay in 'After Image' by film theorist Peter Wollen, taking up the post-May 68 political opportunity among a large section of the French population and elsewhere in Europe thought to be open to revolutionary ideas.

Although funded for, and mostly by, television the group's political initiatives were ultimately all rejected for screening on TV. Instead of seeking open-ended communication with a TV audience, a 'deconstructive western', Wind from the East starring Gian Maria Volonte, was held up by Wollen as an example of counter-cinema, of 'making films politically'. It was originally to be made with student radical Daniel Cohn-Bendit who dropped out early to be replaced, problematically as it turned out, by Brazilian filmmaker Glauber Rocha. Not unlike the role of citation in the first phase of Godard's work, ambition for integration with genre here in the service of revolutionary ideas remains unrealised - the overall 'closed off' effect is “oppressive” (Morrey 95). Such critiques amplified by the negative reactions of audiences at Cannes and the New York Film Festival highlighted the contradiction at the heart of making “political films politically” or specifically, in this case Godard's stated intent of showing the way to “destroying (bourgeois) cinema” which brought him into conflict with Glauber Rocha.

Godard acknowledged Gorin's work in a crisis in bringing a new philosophical rigour to the film's structuring. If the negative reception by 'bourgeois' audiences might be taken as an indication of Wind hitting its political target, at the same time it severely limited scope for its wider circulation. For further discussion of these issues see James MacBean's essay - "Godard and Rocha at the Crossroads" - in 'Film and Revolution' op cit., also Richard Brody 347-8)

Robin Wood commented that “the assumption behind the DVG films was clearly that the revolutionary impetus of May 68 would not be sustained and it had not been easy for Godard to adjust to its collapse” (Lyon ed. 221). After he had sufficiently recovered from near fatal injuries sustained in a mid-1971 motorcycle accident, he and Gorin took stock. It was decided to attempt a return to commercial cinema without abandoning the aesthetic and political principles of the preceding years. Godard's problem remained foregrounded: how does a political radical make a film within the capitalist system? For Phillip Drummond (see his opening quote in 6(11) summarising Godard's work), the DVG films are too often “raw, inchoate and struggling to convince.”

|

| Yves Montand (centre), Jane Fonda (right) Tout Va Bien |

In Tout va bien/All's Well (1972), Yves Montand is a former New Wave film director radicalised by May 68 and Jane Fonda an American radio broadcaster doing political commentary, a media couple who become involved in a workers' factory occupation. The couple begin to see how they too are systematically alienated and exploited in their work situations. The DVG was replaced by Godard and Gorin in the credits. The heavy use of rhetorical Marxist-Leninist commentary by Godard and Gorin in much of their other work together is abandoned, “the tyranny of words” giving way to what MacBean refers to as “a materialist mise-en-scène solidly rooted in things” (178). Complex use is made of Montand and Fonda in a dialectic of star personalities/fictional characters to explore the relationship of intellectuals to the class struggle, in what Wood called the “most authentically Brechtian of Godard's films to date” (ibid 222).

|

| Godard, and Anne-Marie Miéville |

Sonimage

Anne-Marie Miéville nursed Godard through more than two years of intermittent hospital treatment following his accident. For the first time he found himself involved with a woman who as a stills photographer, director and screenwriter “was on the same side of the camera as himself.”

“For her he was simply Jean-Luc. She relentlessly criticised the assumptions of the Maoist revolutionary discourse and argued that it had continuously ignored the reality of daily life in France. The answer to the inadequacies of commercial cinema was to be found in the analysis of how the image functioned in daily life, not in didactic revolutionary films.” (MacCabe) There is a certain irony here given an original platform in Godard's cinema is the politics of everyday life.

Godard and Miéville set up a small studio 'Sonimage' in Paris but soon moved to Grenoble in 1974 and subsequently to Rolle. They used footage from an unfinished DVG film on the Palestinian issue edited into the little-seen Ici et ailleurs/Here and Elsewhere (1974) as “a classic feminist work” to dramatise the debates that informed Godard and Miéville's Numero Deux (1975) in which film and video are combined to examine sex and politics in the home. “The argument, however, is not based on a simple moralism but an analysis which links global political relationships to our familial conflicts” the images as the mediating term: “we cannot understand the ‘elsewhere’ of Palestine because we do not understand the ‘here’ in France” (McCabe (245). Further collaborative work followed on two series for French television constituting a whole new use of the small screen.

|

| Isabelle Huppert, Jacques Dutronc, Sauve qui peut (la vie) |

In 1979 Miéville urged Godard to return to cinema and to use what they had learned from their experiments. The result, Sauve qui peut (la vie)/Every Man for Himself (1980) co-scripted by Miéville with Jean-Claude Carriére, was shot with a tiny crew and was more frankly autobiographical than Godard's earlier features (Colin MacCabe in “Jean-Luc Godard a life in Seven Episodes (to date)” in Son + Image 1992.

At the time of completing “Godard and Narrative” in 'Narration in the Fiction Film' following Godard's return to cinema, Bordwell had seen only Sauve qui peut (la vie) (1979) and Passion (1981), in both of which there appears to be “a retreat from radicalism.” Bordwell found them “almost completely assimilable to art cinema's narrational mode” with a fairly straightforward use of art-film schemata, protagonists revealing reasonably consistent character traits and a quiet use of disjunction never posing the “glaring problems” of his early films by opening up to scrutiny stylistic work no less experimental than in the years 1968-72 (334).

|

| Myriem Roussel, Hail Mary |

The above two films are closely linked with Prénom Carmen (1983) and Je vous salue Marie/ Hail Mary (84). Their fictional worlds are interchangeable and characters overlapping, suggesting ambiguously that “a new beginning” might still be on track with the innovative use of images and music from the preceding two films forming the so-called 'cosmic' period (Morrey 132). Adrian Martin finds “a more expansive, lyrical, poetic Godard - if still iconoclastic and cheeky, but now interested in classical art, classical music, religion and the great myths (review of Helas pour moi, Film Critic 1995).”

Morrey sees these films almost splitting Godard's career in half with “the development of an approach to narrative, character, dialogue and shot composition that will characterise all of his major features through the 80s and 90s up to and including Éloge de l'amour (2001).” Despite the stylistic rupture Godard's interest continues in the recurring theme of the pairing of love and work, a preoccupation noted in Masculin féminim that is irrevocably separated in our societies by the capitalist division of work and leisure (ibid 133).

After the first four films of his return to cinema, Godard’s succeeding work, perhaps with the exception of Nouvelle Vague (1990), seemed to be suggesting a 'forever unreeling Godard,' his films increasingly perceived as 'inscrutable and hermetic'. In his video work, Histoire(s) du cinema ,10 years in the making of cinema's epitaph, the deeper concern with history and its relationship with collective and individual memory is apparent. A more than complete recovery of critical consensus or, one might say, vindication if any was needed, came with what are Godard's testimonials on cinema and politics: Goodbye to Language (2014) and The Image Book (2018).

Goodbye to Language is a visually revelatory experience in revivified 3D with an opaque plot. The opacity is a defensible challenge in which David Bordwell, for one, locates a theme : “the idea that language alienates us from some primordial connections to things” (see Wikipedia entry). This seemingly carries an echo in Alexander Kluge's not well-known (at least in the anglo-sphere) theorising and work with film collage in the New German cinema - see forthcoming part 6 (17) of this series.

Godard made more than 100 films including 30 fiction features (15 between 1959-67) and 4 feature length essays for cinema exhibition. From 1976-8 Godard and Miéville made 15 hours of television in two series: Six fois/Suret sous la communication (1976) 6 programs of 100 mins, each in 2 segments - “an end point of the earlier essayist tendency in his films.” France tour détour deux enfants (1978) 12 programs each 26 mins “more of an announcement of what is to come in the early 80s - more philosophical and poetic”.

In the 2012 'Sight & Sound' Ten year World Poll Godard was rated second top director by the critics with 238 votes after Hitchcock (318) and just above Welles (231), then Ozu (189) and Renoir (179). Godard (with Hitchcock and Bergman) is one of only three directors with 4 in the top 100.

|

| Godard (r) shooting Breathless (1959) |

The results of 2012 and 2022 polls are respectively juxtaposed in this summary. Breathless (13/38), Le Mépris (21/54), Pierrot le fou (42/84), and Histoire(s) du Cinéma (48/84). 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her (106), Vivre sa vie /My Lfe to Live (152) are also in the top 250.

Godard and Cinema

Filmography

New Wave 15 features 1959-67: Breathless to Weekend Dziga-Vertov Group (Gorin): Vent d’ Est/Wind from the East (69) Tout va bien (72) Letter to Jane (72) Sonimage (Miéville) : Numero deux (75) 'Second New Wave' : Sauve qui peut (la vie)/Every Man for Himself/SlowMotion (80) Passion (81) JLG Films Prénom Carmen (82) Je vous salue Marie/Hail Mary (83) Détective (84) Soigne ta droite/Keep Your Right Up (87) King Lear (87) Nouvelle Vague (90) Allemagne 90 neuf zero/ Germany Year 90 Nine Zero (91) Hélas pour moi (93) For Ever Mozart (96) Éloge de l'amour/ In Praise of Love (01) Feature length essays: Notre Musique (04) Film Socialisme (10) Adieu au langage/ Goodbye to Language (14) Le livre de image/The Image Book (18) Select other: Le Gai Savoir/The Joy of Learning (68) Ici et ailleurs/ Here and Elsewhere (76) Scenario du film Passion (82) Histoire(s) du Cinéma (88-98) The Old Place (98)

*************************************

Douglas Morrey Jean-Luc Godard French Film Directors Series Manchester University Press 2005

James Roy MacBean Film and Revolution Indiana University Press 1975

Richard Brody Everything is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard 2008

Colin MacCabe Godard:A Portrait of the Artist at Seventy 2004

Pam Cook “The French New Wave” pp. 253-5; “Authorship:Counter-Cinema” pp. 305-8 Cook & Bernink eds.

Peter Wollen “JLG” essay in Paris Hollywood : Writings on Film 2002; “Godard and Counter Cinema: Vent d'Est” essay Readings and Writings Verso 1982 first published in Afterimage 4 Autumn 1972

Raymond Bellour & Mary Lea Bandy Jean-Luc Godard Son + Image 1974-1991 MOMA 1992

Robin Wood “Jean-Luc Godard” International Dictionary Directors Ed. Christopher Lyon 1984

Michael Witt “The Death(s) of Cinema According to Godard” Screen 40/3 Autumn 1999

David Bordwell “Godard and Narration” Narration in the Fiction Film 1985

V.F.Perkins “Vivre sa vie” review in The Films of Jean-Luc Godard” Movie Paperback 1969

Adrian Martin “Beyond the Fragments of Cinephilia” in Cinephilia in the Age of Digital Reproduction 2009

Susan Sontag “Godard’s Vivre Sa Vie” essay in Moviegoer republished in Against Interpretation 1967

Jean Collet Jean-Luc Godard An investigation into his films and philosophy English edition 1970

Martin Rubin entry on Vivre sa vie in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die 2003 edition

Craig Keller Jean-Luc Godard Great Directors Senses of Cinema 2003

Previous entries in this series can be found if you click the following links

Sixty Years of International Art Cinema: 1960-2020 - Tables and Directors Lists to Accompany Bruce Hodsdon's Series

Notes on canons, methods, national cinemas and more

Part One - Introduction

Part Two - Defining Art Cinema

Part Three - From Classicism to Modernism

Part Four - Authorship and Narrative

Part Five - International Film Guide Directors of the Year, The Sight and Sound World Poll, Art-Horror

Part Six (1) - The Sixties, the United States and Orson Welles

Part Six (2) - Hitchcock, Romero and Art Horror

Part Six (3) - New York Film-makers - Elia Kazan & Shirley Clarke

Part Six (4) - New York Film-makers - Stanley Kubrick Creator of Forms

Part Six (5) ‘New Hollywood’ (1) - Arthur Penn, Warren Beatty, Pauline Kael and BONNIE AND CLYDE

Part Six (6) Francis Ford Coppola: Standing at the crossroads of art and industry

Part 6(7) Altman

6(8) Great Britain - Joseph Losey, Lindsay Anderson, Karel Reisz, Richard Lester, Peter Watkins, Barney Platts-Mills

6(9) France - Part One The New Wave and The Cahiers du Cinema Group

6(10) France - Part Two - The Left Bank/Rive Gauche Group and an Independent

6(11) France - Part Three - Young Godard

6(12) France - Part Four - Godard:Visionary and Rebel