Opening scene:

A vast plain in Wyoming. The “Laramie” conference has begun. It’s 1866 and a line of US Army officers on horseback faces a line of Sioux braves on horseback. Their leaders are conferring. The Sioux’s “sacred hunting grounds [are] silent and empty of buffalo, elk and beaver…food, clothing and shelter vanished forever…starvation and sickness where once there was plenty.”

Jim Bridgers (Van Heflin), the most renowned pioneer, trapper and scout of the times, is pleading the Sioux case. This is the fourth treaty, he says, but all have failed and the Sioux have been driven off their sacred lands. And now, says Bridgers, The Bozeman Trail has been built for prospectors and settlers to access the new gold fields in Montana. It runs through the middle of the Sioux’s last hunting grounds and if the wagons and troops are allowed up the Trail, it’s the end of the buffalo in Wyoming. “The buffalo means everything to these people. It’s their food, their clothing, skin for tipis, bones for weapons.”

When Bridgers is told The Bozeman Trail is the only feasible route, he reminds the gathering that he and John Bozeman have raced wagons - Bozeman over his Bozeman Trail and Bridgers over his Bridgers Trail “west of the Big Horns, outside of Sioux Territory. It took me 34 days to get to Virginia City, just two days longer than Bozeman. If we want peace with these Indians, it’ll cost us something. The Sioux has already paid plenty. Two days extra travel isn’t too much for us to pay.”

Bridgers is then accused of sympathizing with the Indians, as one of his travelling companions is Indian (although, as Bridgers points out, she is Cheyenne, not Sioux and has no interest in the Sioux’s hunting grounds). His other companion, a white trapper, is accused of having “lived among the Indians”.

Chief Two Bears asks: “If no-one will listen to Jim Bridgers, will they listen to anyone else?” Good faith and an agreement over a treaty is requested, but Bridgers suddenly reveals the Army has already built a fort on The Bozeman Trail. Chief Red Cloud (John War Eagle) stands, and speaking in English, accuses the white men: “We would have learned about [the fort] after we signed the treaty…You pretend to parley with us for a road through our lands, but soldiers have been sent to steal a road before we say yes or no.”

|

| Van Heflin, Susan Cabot, Tomahawk |

He speaks to the other Chiefs in Siouan and they ride away from the conference, leaving the treaty unsigned. Bridgers translates: “He says white man’s promises are written in water. In other words, gentlemen, he said you are a pack of liars and this peace conference is a fake.”

All this unfolds in the first six minutes. It’s an exceptional and highly polished set-up for the 75 mins to follow as the underrated and neglected Tomahawkexplores the plight of the Sioux.

Buffalo hunting grounds are central to the Sioux’s existence and if you don’t want forensic detail on how important buffalo and bison were to Native Americans, look away now, or skip the next paragraph. It comes from Glenn Frankel’s laudable The Searchers The Making of an American Legend (Bloomsbury, 2013).

“The dead bison provided food, hardware, clothing and shelter. Each corpse belonged to the man who had killed it. One of the women in his household would make a quick slit under the belly to allow the steaming insides to cool and to minimize bloating, then pull out the stomach and intestines, which would be cleaned, stuffed with meat, and roasted. The hot, still-quivering raw liver was usually shared among wives and children, who wolfed it down immediately. The tongue was another delicacy; it would be boiled and saved for later. The front shoulders were removed at the joint, cut into thin slices, and spread along the grass or hung on poles to dry into jerky. The stomach lining was washed and used to carry water or as a cooking container. The bladder was inflated like a balloon and dried for use as a water canteen or to store food. The footbone was separated from the foreleg and the metacarpal was used as a sharp fleshing tool. The sinew was stretched for skin, thread, and straps. The hide was staked out, dried, and tanned for use as a teepee cover, clothing, robes and blankets. The horn sheaths from the dried skull became drinking cups. The mashed brains were stirred into a paste to soften and waterproof the buffalo skin.”

Universal purchased the rights to Daniel Jarrett’s story Tomahawk in 1947 and it seems highly likely the success of Delmar Daves’ Broken Arrow in 1950 led to the film being greenlighted. Scriptwriter Silvia Richards (Secret Beyond the Door and the original story for Rancho Notorious), along with seasoned co-writer Maurice Geraghty extract material from three well-known Sioux-US Army conflicts known as The Sand Creek Massacre, The Fetterman Massacre and the Wagon Box Fight. Apart from Heflin and the Chiefs, the cast includes Yvonne de Carlo, Alex Nicol, Susan Cabot and in a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it moment, Rock Hudson.

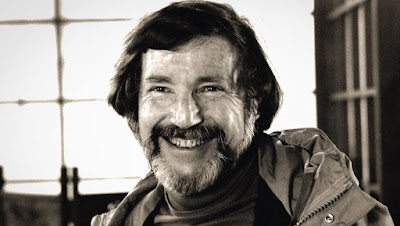

In his 41-year career George Sherman directed more than 100 films and nearly 40 television episodes (including Rawhide, Naked City, Daniel Boone and Route 66). Known as a B-feature director, Tomahawk was his 76thfilm and in one 5-year stretch, he directed 45 Westerns, all around 60-minutes in length. He totaled well over 70 Westerns and in 1955 made a feature entirely from the Native American point-of-view, Chief Crazy Horse, unfortunately casting Victor Mature in the main role.

The digitally mastered DVD from the Universal Vault Series is as good as it gets and handsomely renders Charles P. Boyles’ Technicolor cinematography.

|

| Tomahawk, DVD cover |