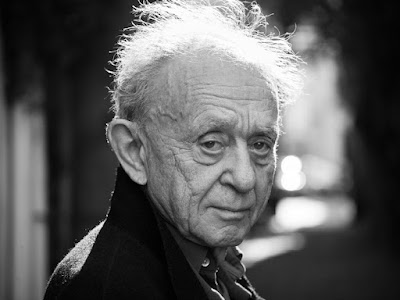

Editor's Note: This is the second part of an interview with documentary film-maker Frederick Wiseman recorded by Melbourne author and critic Tom Ryan. It is published to coincide with a season of Wiseman's films being screened at the forthcoming Sydney Film Festival, the ARC Cinema at the NFSA in Canberra and ACMI in Melbourne. Check the websites of each for information about screening times. The first part of the interview which was prefaced by the SFF's catalogue notes and a short introduction by Tom can be found IF YOU CLICK HERE

****************************************

To what extent do you as a filmmaker ever feel like that guard I’ll always remember from Primate, just sitting and watching while the chimps “behave” in their cages?

Mmm. To what extent do I feel like that?

Yes, as a filmmaker remaining apart from the action?

Well, part of my interest in making these movies is to record contemporary experience. So I feel like I’m doing my job. I’m not like the guy in Primate who’s making observations about the sex life of the gorillas. My job is, as I define it, to make a movie about an aspect of contemporary experience and to organise it in a dramatic form. So I’m not simply observing, or not only observing. I’m there to try to think about what the experience that I’m watching means to me, and then ultimately, in the editing stage, organise it in a dramatic form and in a way that fairly presents the experience I had in making the film.

|

| Primate |

So it’s not in any way a passive role, because you’re constantly having to make choices. Choices about the subject matter, choices about what to shoot, how to shoot it, how to edit the material in relation to other sequences, how to impose a form on the film: all of those things represent choices that have to be quite consciously made.

However, there is also still the camera between you and the immediate moment that you are observing that kind of forces you to remain apart. To go back to Primate, my memory of the film – and it’s been a while since I’ve seen it – is that the soundtrack is full of the sound of cage doors being slammed shut. That there’s a sense of everybody on both sides of the bars being prisoners. I was kind seeing of you in that as well, reflecting on what you were doing.

Well, no. You hear the doors clanging. It’s not because I added that sound to make that metaphoric point. It’s because that’s what you hear. It may also make the point that you raise, but it’s not something that’s imposed on the experience. It’s something that you recognize as part of the experience.

Do you regard the kind of work you do generally as essentially anthropological?

No. Because I don’t proceed by any theory. And I’m very interested in dramatic structure and, um, I don’t do studies in the sense that I understand anthropological study. I don’t see myself at all as an anthropological filmmaker, which doesn’t mean that there aren’t resemblances. But I don’t see myself that way, nor do I think about the kinds of things that anthropological filmmakers might think about, at least according to their literature.

When I interviewed Errol Morris a few years ago, he spoke about you as someone who deals with “man at his most dysfunctional, and insane” [the sound of a groan of protest about to come from Wiseman] and he also compared you to Samuel Beckett [a burst of laughter] and your films as “theatres of the absurd”.

|

| Near Death |

Well, I certainly like the comparison to Beckett because I’m a great admirer of Beckett. Ah, ah, but I also think that in my movies you get to see people doing, to the best of their ability, lots of kind and generous things. For example, I thought the doctors and nurses in Near Death were extremely sensitive to the needs of the families, which was nice to see. I would say the same thing about the doctors and the nurses in Hospital. Ah, ah, some of the cops in Domestic Violence and Public Housing, the same thing. Some of the teachers in High School 2.

My goal, or one of my goals in any case, is to give as rounded a view of human experience as I can and I think I would be doing myself a disservice and being unfair to the people in the movies if I only went for the absurd. It makes the absurd more interesting, actually, when you see it in contrast to the kind and generous.

I haven’t seen all your work. In fact, from my viewpoint, we’ve been denied far too much of it in Australia…

Just let me ask you something, Tom, which may be out of line. If you felt it was appropriate to wonder out loud, to pose the rhetorical question in your article as to why my films have not been shown on Australian television… I think that only one of them, Missile, has ever been shown…

And I missed it because I didn’t know it was on.

Other than that nothing. I’m just saying – you may not feel it’s appropriate, but if you felt it was I’d appreciate it.

|

| Domestic Violence |

My opening has already been written and that’s a point I’ve made. I’ve long been championing your work here, if it’s not out of line for me to say that. I’ve been criticising Festival directors around the country for the negligence since the end of the ’80s. We had Ballet in 1995; we had Near Death shown at the Cinematheque in ’89. Um. And we’ve got Domestic Violence. But the others, since the National Library collection here moved in other directions, we simply don’t have access to.

Yeah. The National Film and Sound Archive used to buy them all as they came out each year. And then they stopped. They don’t do that any more.

I used to use one of the films it holds, The Store, every year in my Cinema Studies classes when I taught at university. And you have many other admirers in Australia even if they don’t get as much access to your work as they might like…

Anyway, I was going to say that, from the films that I’ve seen, there’s a kind of darkness that hovers around the edges, except perhaps in the second half of Ballet, which is kind of celebratory in a way that the others aren’t. Are you conscious of that? Am I misreading it?

No. I don’t think you’re misreading it. It’s also true of the Comédie Française film.

Which you made immediately after it?

Ah, yes. I made it in ’96. I think Ballet was ’92 or ’93.

I was going to ask you in relation to Domestic Violence, why Tampa?

Because I got permission there. It’s very hard to get permission to shoot in a shelter. The city authorities in Tampa liked the idea of a movie and they’re pretty well-organised to try and cope with domestic violence issues. And the co-ordinating council of the city helped with all the things we had to deal with: the cops, the sheriff’s office, legal aid, the court, the shelter and the social agencies. So they liked the idea of it and it resulted in getting me access.

Did you attempt elsewhere and were rebuffed?

No, I didn’t actually. At least I never attempted formally, but I did informally and I got the answer that it’s not even worth asking ’cause you’ll never get into the shelter. And, for Tampa, I met somebody who knew all the people involved in domestic violence in Tampa and it turned out to be quite simple because this couple organised a lunch where they invited all the significant people who dealt with domestic violence. And they introduced me and I spoke for a couple of minutes and I answered their questions and then they said OK.

I know you never use interview material in your work and I was wondering if you ever considered leaving out the information session in Domestic Violence because it was too explicit.

No. Because it happened without my prompting and tours were common in the shelter, I thought it was OK to include it. I mean, I’ve used that kind of event before when I’ve stumbled across it because it helps me. For instance, there’s a scene in Meat where some Japanese visitors are being taken on a tour of the stockyard and I used that. I’m not comparing the shelter to the stockyard: the similarity is the tour. And I thought there was useful information in that tour: in the same way that it was orienting the women in the tour, it orients the viewer of the film.

Your films vary in running-time, but they’re often very long. To what extent does the material you’ve shot dictate this?

To a very large extent. In fact, I feel that my obligation to the subject matter and to the people who’ve given me permission to film them is greater than my obligation to any network backing me. The people in Domestic Violence gave me intimate access to their lives and I feel that I have an obligation to make a film that fairly presents that.

Domestic Violence is really a film that’s dependent on words, because you’re dealing with a lot of people’s stories. And it takes time to tell those stories. So if you just cut to the punch-line, so to speak – if you did that in Domestic Violence you’d be cutting to the line where she says, “He put out his cigarette on my arm,” or “He tried to kill me” – it’d be like, you know, one of those cop shows. I feel an obligation to create a context, and that takes time.

I mean, I’ve made films that are shorter. They vary from 73 minutes to close to six hours. But I feel that I have a greater obligation to the subject matter than I do to any broadcaster. My goal is that the final film be a fair report on what I think I found. And in the United States, PBS has accepted that. Because even Near Death, which is close to six hours, ran without interruption.

They ran it for the whole six hours?

They ran it on a Sunday afternoon, a grey, winter Sunday afternoon from 2 in the afternoon to 8 at night. There wasn’t any football on and it drew quite a large audience. And most of the films, the ones that are three or three and a half hours, are run in prime time, they start at 8 or 8.30pm, or occasionally 9, and they run their full length. Naturally, I like that.

|

| Welfare |

To what extent do you think the length affects the wider distribution of your work?

Well, I’m sure in terms of television sales that that’s an issue. But, on the other hand, they would be very different films if I cut them. I’ll give you an example. Many years ago, during the war in Vietnam, I did a film on army basic training [Basic Training, 1971] – I think it’s 89 minutes – and CBS wanted to run it if I’d cut it to 54 minutes as a whole 60 Minutes program. I said no. I said that if you liked the film at 89 minutes, it’s not gonna be the same film at 54 minutes, and it’s gonna present a very different view of army basic training. And several years later the same thing happened when I made Welfare, which runs for three hours and which they wanted me to cut back to 54 minutes.

So there are two situations where I know that the film didn’t get a wider distribution because I refused to cut it. And I’m sure that’s true with many television networks around the world. The programming times are arbitrary choices too. I mean, people say they have to be 54 minutes. Well, that’s just as arbitrary as my saying they have to be two hours and three quarters. Except it’s the custom.

Errol Morris says he’s been trying to persuade you to put your films on DVD. Is that possible in the near future.

Yes. It’s possible. I may do that, but I actually haven’t had time to investigate that. [Wiseman’s work is now readily available on DVD through his website: http://www.zipporah.com]

What do you think of digital video?

Well, I’ve never shot anything in it and I don’t know that much about it. Of the little that I’ve seen, I don’t think the quality is anywhere near as good as film. And as long as I can continue to get the money, I’m going to continue to work in film. You know I understand why people shoot in digital video: it’s much less expensive. Or at least theoretically it’s much less expensive: I don’t know whether, as a result, people shoot a lot more than they would have with film. But I just don’t think the quality is there.

For the next film that I do, maybe I won’t be able to raise the money that I need, so I’m not gonna stop working because I can’t shoot on film. But I’m gonna make a big effort to always try and do it. [Soon after this interview, largely for budgetary reasons, Wiseman began shooting his films digitally.]

You’ve had a major influence on other filmmakers. Who are the people who have influenced you, whose work has somehow affected the way you work, the way you think about your work?

Well, I’m not very good on that kind of question. I think actually I’ve been much more influenced by literary sources than film sources. “Literary” sounds too fancy: I’ve been influenced by the novels and poems and plays that I’ve read than by the films that I’ve seen.

Which novels and plays and poems?

Well, Beckett, Ionesco, Philip Larkin, you know. The usual villains.

And in what ways?

Well, for instance, the best book I ever read about film editing was Ionesco’s essays on playwriting [Notes and Counter Notes: Writings on the Theatre, 1963, by Eugène Ionesco]. Because in his writing about the play and about how he constructed his plays, it was as if he was writing about movies. He wasn’t talking about the technical stuff, but about how you construct a play and deal with ideas in a play. And I just translated everything he was writing into my own issues in film editing.

What filmmakers have you admired?

There was a film that I saw early on, even before I got started, called Football made by somebody named Jim Lipscomb, and it was about two high school football teams getting ready for a championship game in Miami. I think I saw that film early in the 1960s and it really opened up my eyes to some of the possibilities for documentary film, because I’d always been interested and I hadn’t yet made any, or any that had seen the light of day. And that made me more aware of some of the possibilities and that happened to correspond with some of my particular interests.

Do you watch other contemporary documentaries?

Yeah. When I get a chance because I work most of the time, and when I’m not working I travel a lot, go skiing or something. I don’t get the chance to see many movies at all, whether documentaries or any other kind. Probably in the last year, I’ve seen four movies.

|

| High School |

There’s an austerity to your work – and this comes from left field – that reminds me of Bresson’s films.

Oh, that’s a high compliment. Bresson is somebody I admire and I’ve seen a lot of his work.

I mean, in the first High School, there are sequences that actually follow the same strategies as in Lancelot du Lac, made a few years later – of close-ups of hands and feet moving – and so on that remind me of the kind of abstraction at work in Lancelot.

I’ve never seen Lancelot.

It’s full of the sounds of the armour and shots of feet in stirrups and hands clutching lances, and you get the sense of humanity, or the individuals, being broken up into these various aspects…

Oh that’s interesting. I’ll have to see if it’s available here. It must be somewhere.

One final thing: I believe you’re currently working on a fiction feature?

Yeah. I finished a fiction film in April. It’s called La derniere lettre, based on a chapter from a great Russian novel called Life and Destiny by Vasili Grossman. I did it originally as a play in France about two years ago and then as a result of that I got the money to do a movie. I didn’t shoot the movie as a play, but it’s based on the same source material. And it was shown in Cannes this year as an Official Selection and it’s gonna open in Paris in November and in the States in January. Maybe it’ll be shown in Australia at the festival next year.

It might have been ready before the deadline this year, but with all the work that was going on getting it ready, I missed out on sending it to Melbourne.

I understand it’s your second fiction film?

About 20 years ago, I did an experimental thing called Seraphita’s Diary. It never got much of a distribution.

Why the interest in fiction?

Why not? I happened to read this novel, Life and Destiny [also written by Grossman, in 1960], and I thought this chapter would make an interesting movie. It wasn’t something that lent itself to being a documentary, so why not try it? I don’t feel for ideological or any other reasons that I’m bound to one particular form. In the same way that I’ve occasionally directed a play, it’s because it was fun. It was interesting to try something new. And if I come across other material that I think might make a good fiction movie, I’ll do it. But I lovemaking documentaries and, of course, I’ll continue to do that.