|

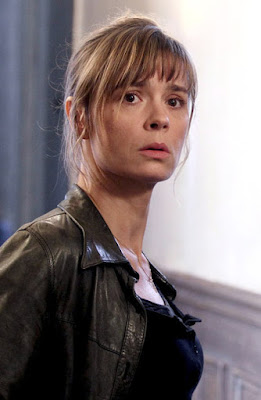

| "ever luscious Senta Berger, The Quiller Memorandum (click on any image for a slideshow) |

"Excuse me, do you have a light?"

"Certainly."

"Do you smoke this brand?"

"No, I don't think I know that brand."

"Perhaps I might introduce it to you?"

"Thank You"

This inspired twaddle from screenwriter Harold Pinter and presumably the original author of the novel by Trevor Dudley Smith, AKA Adam Hall, is the code used in The Quiller Memorandum from the year 1968 with which assorted "agents" from "Our" side signal recognition.

|

| Alec Guinness |

This is only the beginning of a movie set in 1967 Berlin which never once alludes to the Cold war, or the Wall, or the Communists and the quarantined East Berlin regime.

In fact, the notion of cold war which might have been the movie's signature, is instead buried beneath a kind of re-invented espionage thriller apparently dealing with hidden "neo-Nazis", although even that definition is largely unspoken in favor of the adjective "extreme."

Pinter's completely extraordinary screenplay for this very smart movie not only deconstructs the spy genre but purposefully drains it of most, if not all, tension, and the usual nailbiting that goes hand in hand with the genre. There is one car chase and one very mutely conducted drug induced inquisition from the wonderful Max von Sydow in close-up, along with only one killing at the beginning, and two aborted killings later, in what is more or less the climax of the picture.

|

| "overly unctuous" George Segal |

Pinter really goes to town with his trademark "pointless" dialogue for supporting players George Sanders, Alec Guinness from the opening and at the end, as well as Bobby Helpmann through the picture. Each only play three scenes. The three of them are flawless performers for Pinter's universe of non-communication, a curse of the civilised human condition with which he joyously plunders the spy genre.

Michael Anderson who directed this with great efficiency and attention to detail, was never going to set the temple of auteurism on fire. Anderson’s 1956 Around the World in 80s Days is surely one of the most turgid motion pictures ever made. But it feels as though Pinter's elusive and evasive writing leads Anderson into highly personal mise-en-scène territory.

|

| Max Von Sydow |

Two examples: He films the opening sequence of the first agent being murdered with one long 90-second wide shot and a single cutaway to the telephone booth. In the last ten minutes, to open the penultimate sequence he uses precisely the same set-ups down to the time cue but the screenplay aborts any killing, and denies us the obvious expectation.

Similarly, in the one big love scene between ever luscious Senta Berger and overly unctuous George Segal (whose haminess seems supremely if contrapuntally apt for this endlessly amusing picture), rather than simply stage and film the love scene with medium close, close and reverse close shots, he arranges four setups/angles for the two shots and continuously cuts between them during real time, effectively alternating and multiplying the point of view and disrupting any predictable immersion in the sequence. The distancing effect is outstanding.

|

| Robert Helpmann |

Somehow or other I missed this movie over the decades although I'm as much a fan of espionage as the next overgrown boy-man. Anderson's achievement here, with the very personal ring of Pinter's world view, is a unique entry in the field I think. While not generically similar I would rank this picture as highly as another unnoticed and rarely praised British masterpiece from the crooked cop/kitchen sink school from the same year 1968 as David Greene's The Strange Affair with Jeremy Kemp and MIchael York, from a Jeremy Thoms novel.

The screens are all from a very fine Twilight Time Blu-ray which easily beats the UK Network release for superior grading, color, and picture quality. Buy, if you can still get your hands on it.