The series on the 60 years international of art cinema 1960-2020 by Bruce Hodsdon continues with thoughts on New York film-makers

These notes are accompanied by a set of summary table and decadal lists of art film directors 1970-2020 (click to link) which contain 5 lists 1970-2020 including a list of women art film directors over the full 60 years from 1960),

*************************

|

| Shirley Clarke |

|

| Elia Kazan |

Kazan and Kubrick, (who will feature in the next essay), with their filmmaking origins in New York, like John Cassavetes, retained the spirit of independence within the framework of the new Hollywood while Shirley Clarke remained an integral part of the New York film scene.

***

One impediment of ageing I’ve noticed is how quickly a recollection, even of a positive viewing experience, can seem to fade or simply be pushed off the mindscreen and requiring prompts . My clearest recollections are of my earliest experiences of going to the movies or of landmark films through childhood into my teenage years. Three Kazan directed films I count among the latter were given the primary impact by the on-screen presence and performances of Marlon Brando beginning for me with Viva Zapata(1952) at age 13 and in the following three years, On the Waterfront (1954) and James Dean in a performance perfectly capturing the zeitgeist of a changing audience in East of Eden (1955). Brando fired in the role of Emiliano Zapata as the leader in the demand for land rights for the peasantry in the Mexican Revolution 1910-20, played then as only the young Brando could do, in taking a stand for the New York longshoremen so regaining his dignity by informing on corruption in On the Waterfront (1954)*.Although I couldn’t have articulated it as such back then, I was experiencing for the first timesomething fundamentally political, a nascent sense of the perplexities of revolution being dramatised on the screen. This was really encapsulated for me in the cross currents generated with Brando in two supporting roles: that of Joseph Wiseman as Fernando, a rootless revolutionary seeking power not reform, “a premature Stalinist” as Schickel describes him, and the powerfully staged assassination of the liberal Madero played with the anxious hand rubbing of a temporiser by Harold Gordon. Stripped of his presidential powers and under house arrest leads him up a blind alley in the hope of negotiation, to his murder by a menacing crypto-fascist general. When Zapata finally got power he didn’t know how to exercise it.It started corrupting those around him, like his brother (Anthony Quinn), and he found himself being corrupted. (BH)

|

| Julie Harris, James Dean, East of Eden |

|

| Rod Steiger, Marlon Brando, On the Waterfront |

|

| Marlon Brando, Viva Zapata |

While notably collaborative, especially with actors, Elia Kazan (1909-2003) came to describe himself as “a believer in the dominance of one person [the director] who has the vision” (American Film interview March 76). As Michel Ciment puts it, “if Griffith and Ford are the ultimate references to the classical Hollywood cinema, it can be contended that Welles and Kazan ... [were] the most disruptive forces in modern American cinema. Few directors of the younger generation would deny Kazan's influence on their work” (MC 9).

|

| Dana Andrews, Boomerang |

While the extent of the direct influence of the Method on screen acting is debatable there is little doubt of its place in the in the epoch-changing shift towards greater naturalism in acting styles on stage and screen in the fifties and sixties. Kazan played a major role as a path-breaking director in the Group Theatre and co-founder of the influential Actor's Studio in New York in 1947. Jonathan Rosenbaum comments “that as the principal liaison between the students and techniques of the Actors' Studio and the American cinema, Kazan's contributions and influence were decisive; apart from 'discovering' James Dean, Zohra Lampert, Jack Palance, Lee Remick and Jo Van Fleet, among many others, he directed some of the best performances ever recorded on film” (Rosenbaum 538). Kazan set new standards in location shooting within the South and in his classy thrillers Boomerang (1947) and Panic in the Streets (1950). He also broke new ground in the handling of contemporary themes such as the interrelationship between the individual and the collective, linking his personal evolution to the history of America and the American Dream. Kazan sustained his commitment towards independent production and in writing his own work, setting standards for personal creativity.

|

| Jeanne Crain, Ethel Waters, Pinky |

His film career falls into three chronological segments characterised by an increasingly “personal type” of expression which, in his book on Kazan, Roger Tailleur labelled him respectively as “HE” (up to Pinky 1949), “YOU” (from Panic in theStreets 50 to On the Waterfront 54), and “I” (the subsequent films from East of Eden 55) (quoted Coursodon 161). This seems appropriate for a cyclical creator like Kazan who was chronically dissatisfied with his work, like his heroes turning his back on the past and always forging ahead in new directions. Each new phase “was marked by the conquest of a larger slice of the autonomy he needed to express himself more fully. After Pinky he broke away from the confinement of studio work and what he viewed as the crippling adherence to pre-written scripts. After the triumph of On the Waterfront, he was able to become his own producer, to select his material and collaborate on the scripts, finally with two semi-autobiographical pictures based on his own novels, America America and The Arrangement, he reached the status of complete auteur

|

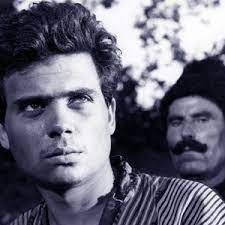

| Stathis Giallelis, America, America |

America, America/The Anatolian Smile (1963), Kazan's most passionately personal film, is too often undervalued. It marks the fulfilment of his notion of “total authorship,” turning away from the stage and devoting himself to writing. It is the first film he wrote himself and was also based on his own novel dealing with a story of his family, his uncle's struggle for survival in pursuit of his American dream, gathering together all the main themes of Kazan's work. In assuming total control he was taking on the risks and difficulties of filming in unfamiliar locations.

Adrian Danks in his review of America America published in 'Senses of Cinema' Annotations, notes how “Kazan points the way towards a fruitful and committed combination of the old influences and the seemingly freer terrain of a truly modern cinema. Kazan's film also pointed back to the influence of the Soviet montage cinema of Sergei Eisenstein and Alexander Dovzhenko, and such breakthrough directors as Roberto Rossellini, a central figure in the fusion of fact and fiction, and whose key film Paisa (1946) is directly and bravely referenced in one of America America's most shocking moments as the bodies of failed revolutionaries are thrown into the sea. America, America keenly reflects Kazan's own influences across American and European cinema...highlighting how to integrate and present such cinephilic allegiances and touchstones.”

|

| Faye Dunaway, Kirk Douglas, The Arrangement |

Kazan's The Arrangement (1969), a film based on his novel, “is both an echo and an ironic commentary” on America, America (Coursodon). It also turns the American trilogy” (East of Eden56, Wild River 60, and Splendor in the Grass 61) into a tetrology by adding a disenchanted view of a man obsessed only with material success.

Drawing on Gilles Deleuze, Richard Rushton finds an over-determining anxiety in Kazan's films which centres on trying to ever more clearly define the American Dream in his work through the unprecedentedly intense transformation of the initial situation with certain actions by the hero resulting in a new situation, filling the gap by changing or modifying that initial situation (Cinema After Deleuze 36).

Kazan acknowledged that The Arrangement(1969) was unusual in that it deals directly with a “successful American” to raise issues of social and psychoanalytical criticism, and has to do with the past, the worth, the nature of America.” It attempts to do this, Kazan explains, without resorting to metaphor such as using the western to make a film about Vietnam, a means of inserting social issues into a genre framework or what Kazan called “substitute pictures.” His later films from Splendor in the Grassto Wild River, America, Americaand The Arrangement, were appreciated in Europe more than in America.

The Arrangement published in 1967 was Kazan’s first novel to become a best seller. In it he writes about “my mother, my father, my youth, elements in my own life motivated by wishing to speak about my extensive psychoanalysis.” For Kazan “Eddie Anderson (Kirk Douglas) in The Arrangementgave up his soul [for material success] just as his uncle Stavros [in America America] did. The story of The Arrangementis how he gets it back.”

The film did not repeat the book’s critical and commercial success. Kazan appeared satisfied with it in Ciment’s book length interview recorded in 1971. Subsequently when its critical and commercial failure were fully apparent, over the best part of the next two decades which were not good times for Kazan, he did not want to talk about it with Richard Schickel. Kazan finally admitted that he should not have written the screenplay himself. Most of all was Brando’s late refusal of the lead role and for Kazan the unsuitability of Kirk Douglas for the role and other casting mistakes. To Schickel its failure which pretty much ended Kazan’s mainstream film career, came across as little more than a cashing in on the novel “hitting us where we no longer were” (428).

Without referring to it as an “art film”, in the Hollywood context Thomas Elsaesser saw The Arrangementas an “example of a film that tries to confront the problem of 'the unmotivated hero’…Yet the film's analytic and reflective mode of narration,” Elsaesser continues, “remains unsatisfactory because Kazan cannot resolve the aesthetic problem of still wanting to find a principle of unity which would hold the film together on the level of motivation,” adding, “that much the same could be said of Arthur Penn's Mickey One.”

* Kazan acknowledged in his autobiography, My Life,that there was an analogy between Terry Malloy’s informing and his own (and the film’s scriptwriter Budd Schulberg’s) testimonies to the HUAC acknowledging that there was nothing in his life “about which I feel more ambivalence” (Ciment 83). Kazan claimed that informing was not the driving force behind the film, the main theme is about the redemption of “a young man who has let his dignity slip away, regains it.” According to Schickel “Schulberg swears that he and Kazan never discussed their informing while working on the screenplay” (283-4)

Jean-Pierre Coursodon, “Elia Kazan” American Directors vol 2 1983

Michel Ciment Kazan on Kazan 1973

Adrian Danks “Elia Kazan and America, America” Annotations on Film in Senses of Cinema Mar. 2012

Jonathan Rosenbaum, Cinema : A Critical Dictionary ed. Richard Roud vol. 1 1980 pp.536-42

Thomas Elsaesser, “Why Hollywood?” in The Persistence of Hollywood 2012 pp. 93-4

Richard Schickel Elia Kazan 2006

Richard Rushton “Kazan and the American Dream” Cinema After Deleuze 2012 pp.36-40

|

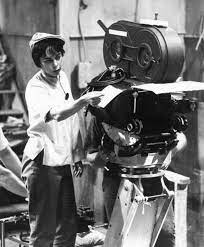

| Shirley Clarke filming The Connection |

Shirley Clarke(1919-97), Maya Deren and Yvonne Rainer, were all dancers before they were filmmakers and this is reflected in their films. Clarke was a leading figure in the New York film scene in the 60s and the 70s with Jonas Mekas co-founding the New York Filmmakers Coop in 1962. Clarke began making short films in 1953 experimenting with editing to choreograph cinematic space and rhythm. To create a “cine-dance” (a term she didn't particularly like) she spoke of using the special abilities of the movie camera to create a new kind of dance in which she also used the natural movement of people, what she called “the dance of life.” This was important in working with actors on her two feature films. She compared the mass audience for Astaire-Kelly and Richard Lester's Beatles dance films with a limited but dedicated audience for ballet and modern dance which was essentially also the audience for cine-dance. Nevertheless she acknowledged that she had more audience in six months for her first cine-dance than she had for her whole career as a live performer. Widely regarded as her masterpiece is Bridges Go Round (1959) “the most widely seen example of a cinematic Abstract Expressionism in the 50s...utilising editing strategies, camera choreography, and colour tints to turn naturalistic objects into a poem of dancing abstract elements.” (Rabinovitz)

|

| Bridges Go Round |

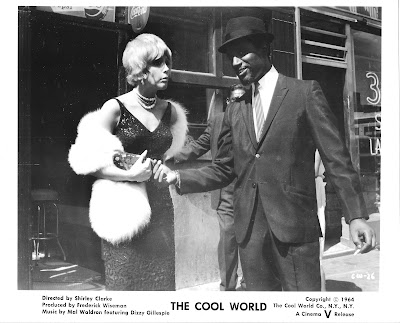

Clarke worked on documentaries with D A Pennebaker and Richard Leacock and was influenced by the then developing style of cinema verité (called 'direct cinema' in the US) which she then adapted in her two feature films The Connection (1962) set in the world of drug addiction, and The Cool World (1961), dramatising without the then obligatory moralising, a story of black street gangs filmed on location in the streets of Harlem. In their realism both films broke new ground in independent low budget New York filmmaking. In The Cool World Clarke successfully challenged the New York State's censorship laws. In the style of both films she spoke of combining direct cinema methods with the rhythm and editing which she said was recognised as “my beat.”

|

| Yolanda Rodrigues, Carl Lee, The Cool World |

Lauren Rabinowitz “Shirley Clarke” entry in Directors International Dictionary ed. Christopher Lyon 1984 Gretchen Berg “ Interview with Shirley Clarke” Film Culture44 Spring 1967

***********************

Previous entries in this series can be found if you click the following links

Part Two - Defining Art Cinema

Part Three - From Classicism to Modernism

Part Four - Authorship and Narrative

Part Six (1) - The Sixties, the United States and Orson Welles

Part Six (2) - Hitchcock, Romero and Art-Horror

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.