Thanks so much Geoff for the introduction and the invitation. Thanks also to StudioCanal and Cinema Reborn for putting together this season of Claude Sautet’s films at the beautiful Ritz cinema for us to enjoy.

******

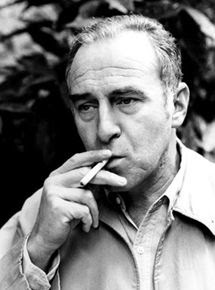

Claude Sautet (above) was described as a “discreet and elegant man” by the French press when he passed away of liver cancer in July 2000, his close collaborators called him a “perfectionist”, an “artisan”, but for me, I think of him as a passionate humanist.

It hasn’t escaped my notice that I am starting this brief introduction of Sautet with his departure; just like the structure of the film Les Choses de la Vie (The Things of Life) we’re about to see: it begins with a car accident – which is a departure of sorts. And this very fact: that the car crash is inthe film before it enters into the characters’ lives was what Sautet loved about the story.

As human beings, our lives intersect with one anotherin media res, whatever it is, it is already happening, we are already in the middle of it. That’s the car accident – and the story of the characters then slowly builds around that. So here, in this talk, Sautet is to be introduced and put into context, before we get to really know him - through his films.

Not much has been written about him or his films in English, so I won’t be surprised if some of you haven’t heard of Sautet before. But he is a brilliant director. An early collaborator of his, film-critic turned filmmaker Bertrand Tavernier, has dedicated his 3 ½ hour documentary on French cinema to Sautet – he regarded Sautet, as well as Jean-Pierre Melville (the Cinema Reborn season that’s just finished), as his two mentors.

Tavernier attributed Sautet’s lacklustre reputation to Cahiers du Cinema’s cold-shouldering of him, “as somebody bourgeois, typical of the Fifth Republic.” But when you watch his films you’ll find there’s a disconnection to this description. However, you can’t blame group of critics who were swept up by the French New Wave. Rohmer, Rivette, Chris Marker, Agnes Varda were amongst these. Godard, Truffaut, and Chabrol were directors who formed the core of Cahiers in the 60s.

Sautet made 14 features in 40 years. It was no secret that his first two films were poorly received. Even though he had cast Belmondo in Classe tous risques (The Big Risk), the actor hadn’t shot to stardom yet with Godard’s À bout de souffle (Breathless) when Sautet’s film came out. And Sautet really took the critics remarks to heart; so much so that he declared he was giving up directing.

It was not until about ten years later that Jean-Loup Dabadie brought him the screenplay to The Things of Life and in an interview, Dabadie said that it was Graziella, Sautet’s wife, who urged him to read the script that was left on their front door on Saturday night. And by Monday morning, Sautet was ringing Dabadie to say he’d be making this film.

This film also marked the start of his work with close collaborators, many of whom stayed with him throughout his entire career. This included the composer Philippe Sarde who was only 18 when he composed the score to this film, (his first film score) and since then worked on all of Sautet’s films. It also sparked the intense partnership with his on-screen muse, the luminous Austrian-born actress Romy Schneider (who went on to star in 4 of his films) and also Michel Piccoli who made 5 films with him.

Claude Sautet was born in 1924 in a Parisian suburb of Montrouge to a working class family. His mother ran a little restaurant and raised him and 3 brothers and sisters by herself. Claude attributed his love affair with cinema to his grandmother, who encouraged him to see films to the extent that she would do his chores for him so that he could go. She also urged him to make a career out of it.

It’s a little known fact was that Sautet was very good with paring down scripts, in fact, a lot of French directors used his services; Truffaut even called him his script doctor. The great actor Jean Gabin said “every screenplay needs a dessert” and Sautet was the best patissier around.

Sautet also had a very fine ear – he loved music and the musicality of dialogue. Sarde said that it was Sautet who taught him that a film score should tell a parallel narrative to that of film, rather than just playing a supporting role. He was interested in the quotidian: how every day people acted, spoke, conveyed their emotions, meant that he wasn’t interested in the grand gestures of cinema - they were too artificial, too theatrical. He wasn’t interested in perfect diction, or showing off couture (notice Romy’s men’s styled blue shirt paired with blue jeans – very chic). But this everydayness doesn’t mean his world is not a complex or interesting one.

THE THINGS OF LIFE

I think that Sautet was often misunderstood. His films didn’t depict a kind of restrained romanticism – he was too passionate for that, he had a fiery temper – everyone knew that on set. The characters in his films are tender and beguiling, struggling and failing too, they come to terms with love and life as real people do. Sautet’s private life at the time mirrored much of the on-screen tensions in this film.

When he met a young actress in a Paris studio in 1968, he wanted to cast her immediately as Hélѐne for this film, she was carefree, smiling, there was something electric about her, but Romy Schneider wasn’t bankable at that time, she was an unknown in France. But Sautet had seen the rushes to La piscine (The Swimming Pool), the film where she fell in love in real life with Alain Delon, and he thought she was sublime. He had to really fight his producers to get her on board and it is this film that launched her to stardom in that country. Romy and Claude went on to have a very close relationship, they had a deep love for each other, as friends, and were each other’s confidants. Her death later in the early 80s really hit Sautet hard, and he had a long hiatus between films. It was Romy who said that The Things of Lifewas more than a film to her, in that it touched her deeply.

Because he wanted so much of the ‘real’, Sautet had a different way of directing. He wouldn’t ask his actors to move like this or say a line like that. Instead, he allowed his actors all the freedom they needed in the rehearsals, to get to the heart of the scene, find the truth in the dialogue, and only after they have succeeded in working that out, would Sautet find a way to film that scene. He also favoured the use of the telephoto lens which meant that the cameras are not directly in front of the actors, instead, his camera is positioned across the street, and this immediately situates the actors in real life, taking in the atmosphere of the street, amongst workers smoking, cafe patrons reading newspapers etc.

As I draw to a close, I’d like to end with the car accident (this accident not only starts the film but intersects it throughout). This scene was a real labour of love – every detail mattered. I hope that you would notice the apple trees in the scene, these were planted there especially by Sautet’s team, and as the shoot was in high Summer, the leaves were actually wilting and Sautet had to run around with spraypaint every morning to make sure they’re green enough for the shoot. Practical though he was, for me, Sautet was a master in the poetics of melancholy. See if you can spot Hélѐne’s scarf that she had accidentally left behind on the dash, this, for Sautet, (and I quote) was a scarf that “swirled like a wisp of smoke around the wheel, and as the car rolled, cigarettes were falling like rain.”

I hope you enjoy the film.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.