At the heart of Ken Loach’s films and television dramas is an anger at the way people suffer because of their social and economic circumstances. From the abused London mum in his 1967 feature debut, Poor Cow, through the protagonists of films like Kes (1969) and Raining Stones (1993) and TV productions like Cathy Come Home (1966) and Days of Hope (1975) to the wee Scottish lad reaching out for a dream of family in Sweet Sixteen and the title character of I, Daniel Blake (2016), they’re all victims of the inequities of their worlds.

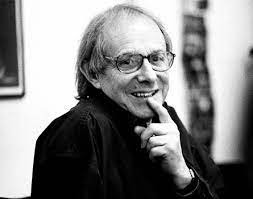

Loach’s compassion for them and his outrage on their behalf is palpable. It’s why the now 85 year-old, Warwickshire-born director has earned a reputation as the British cinema’s champion of the disenfranchised. And it’s made his work the touchstone for a generation of filmmakers concerned to document the workings of their society, not only in Britain but beyond.

Which is why I expected a very different kind of Loach from the one I encountered. I’d anticipated a fearsome vehemence; I got a gentle, soft-spoken man, whose seriousness of tone sits side-by-side with an engaging sense of humour, and who confessed at the end of our conversation that he’d been concerned throughout that I might be insensitive enough to raise the subject of “the cricket”. The MCC wasn’t faring at all well at the time.

However, since Loach has always probed the state of the nation through the prevalent social conditions rather than the on-field exploits of its sportsmen or women, that seemed the best place to begin. And, in his films, those conditions always seem to determine his characters’ destinies from the day they’re born.

Liam, the 15 year-old protagonist of Sweet Sixteen, for example, has little room in which to move. Played by Martin Compston in his striking screen debut – he’s now probably best known for his work in the TV series, Line of Duty (2012 – 2021) – Liam is a smart kid with decent instincts. But his mother is in prison, his father and his grandfather are drug dealers, and he can’t see any way out of his depressed situation.

For Loach, characters and their environments are always inextricably linked. Sometimes they become aware of that, of how their lives have been predetermined; sometimes they don’t. So thank God for Ken Loach: he gives them a voice.

When I spoke to him, Sweet Sixteen (2002) had just been released in Australia and he was taking a break from checking out locations in Glasgow for what was to become Ae Fond Kiss (2004).

************

|

| Martin Compston as Liam Sweet Sixteen |

TR: Paul Laverty [writer of Sweet Sixteen and frequent Loach collaborator] has suggested that the genesis for Sweet Sixteen came from working on My Name Is Joe [1998]. Do you consider what happens to the new film’s Liam as an unofficial back story for the Liam in Joe?

Ken Loach: Not really, no. I think he’s quite a different character. He’s much sharper, much more in control of things, insofar as he can be. I mean, he sees himself as a winner, this Liam, whereas the other Liam has really lost it. This Liam sees his way through to getting a successful result for himself. He doesn’t see himself as a victim, he sees himself as a winner. He’s an optimist. So they’re very different characters.

Yes, but we do leave Liam in Sweet Sixteen on the beach, alone, with a very uncertain future, and the impact of the preceding events could easily change somebody’s outlook on their life.

Yes, that’s true. But that’s the end of that chapter in his life really. The realisation that his mother isn’t the person he’d thought she would be for him. It’s his coming to terms with that illusion – I mean the reality behind that illusion – that is, I suppose, the story of the film. But I think he’s a different guy from the Liam in the earlier film. He’s a different lad really.

|

| "...on the beach alone..." |

You can see why I’m pouncing on this? The two characters are sharing a name.

Yes, yes. Maybe we were a bit lazy about finding another name.

Might this film’s Liam finish up like Joe then?

Um, he’s more likely to finish up like Joe. But, again, he’s too bright really. He’s not an addictive personality. He’s very cerebral. I mean, he works things out in his mind, and he knows which is gonna be the best way for him. I think the probability is that he’ll be in prison – whatever appropriate prison it would be – and he’ll come out nine or ten years later and he’ll have cemented his contacts in the criminal world and that’s where he’ll end up.

The only hope for him is Chantelle really: whether she’ll stick by him while he’s in prison or whether she’ll be just too concerned for her little boy. It’s impossible to say.

|

| Annemarie Fulton as Chantelle |

One gets the sense that all of your protagonists over the years are lost innocents, that they might be saved from disaster, and from themselves, if their social circumstances were different. Is this a view of them you share?

Well, I think the circumstance you live in is another character in the drama in that it affects what happens to you, the person you become and the choices that you have. So it’s another element in the drama and I think that’s true of all good drama.

I mean, we don’t exist in a vacuum. Economics determines the way we spend our lives. I mean, you and me are here at this moment because we’re working: that determines who we are, how we spend our lives, the choices we have. I mean, it’s kind of a self-evident observation, really. It’s not very deep. Often a lot of films and dramas generally tend to imagine that people live in a self-supporting bubble, which I don’t think is true.

Do you regard all of your characters as, in one way or another, ideologically entrapped?

Well, the vast majority don’t have an ideology at all. They don’t tangle with ideas in that way or with a structure of ideas based on an analysis of how they think. They don’t deal in that, but they’re trapped by their social circumstances.

I meant more in the sense that they’re their own worst enemies: they make decisions based on what they perceive as their place in the scheme of things rather than actually being able to step outside those positions and make other kinds of decisions.

Um, yes. I’m not sure. I think it’s true that most people’s perspective is limited to what they know. Again, that’s self-evident. Whatever you can encompass in your mind, that’s the limit of your perspective and that’s the experience of most of them, although not all. We did Land and Freedom about the Spanish Civil War and there they are politically engaged. And in The Navigators, the film we did recently about the railways where workers are caught in the process of privatisation. But being caught in that process does open their eyes to a lot of things.

In a number of the films that I’ve worked on, you see the characters involved in a process of struggle which gives them a whole new perspective and a whole new understanding of the way the world runs. But a character like Liam is very bounded by his world and what he knows of it. So that’s the limit of what he can imagine.

Taking a slightly different angle: there is a kind of remorselessness to your films. Even taking on board what you’ve just said, the further a film goes the more your characters’ options seem to close down. They seem entrapped and unable to escape.

That’s absolutely true, I think. It’s quite rare for someone to be able to get their heads high enough to be able to see the landscape beyond. I mean that’s one of the ironies of the town we shot the film in: they’re in this spectacular physical landscape of the mouth of the river, the hills beyond, the moorland… It’s absolutely beautiful and majestic. Geographically they’ve got a huge, wide panorama. But socially they’ve got a tiny, very small, meagre outlook.

And there is a kind of irony in those characters doing what they do with those limitations in that boundless landscape. I think it’s the inheritance of generations of people who have either been exploited or left with nothing. Some will get out. I mean, because you’re born into it doesn’t mean that you necessarily will stay there. But the majority will stay there because there just isn’t the work and there isn’t the possibility of leaving.

***************

Editor's Note: This is the first part of an interview with the director Ken Loach. It was recorded by Melbourne film critic Tom Ryan as the basis of a feature article for The Age when the film Sweet Sixteen was first released. The Previous posts in this series have been devoted to conversations with Colin Firth (Part One) Colin Firth (Part Two) Lawrence Kasdan (Part One), Lawrence Kasdan (Part Two) Costa-Gavras Jonathan Demme (Part One) Jonathan Demme (Part Two) Click on the names to read the earlier pieces

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.