Long before Colin Firth (b. 1960) attracted international attention as a result of playing Fitzwilliam Darcy in the Andrew Davies/Simon Langton six-part TV adaptation of Pride and Prejudice (1995), his career was well under way. He’d worked extensively in the theatre in the UK and was well known on account of his roles on the big screen there as well as on the smaller one.

|

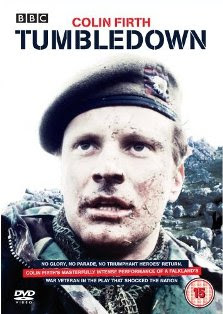

| Tumbledown DVD cover |

Particularly notable was Richard Eyre’s controversial telemovie, Tumbledown (1988), made for the BBC and based on a real-life story about the struggles faced by Lt. Richard Lawrence of the Scots Guards before and after he served in the Falklands. He’d also impressively played the title role in Milos Forman’s Valmont (1989), based on Choderlos de Laclos’s Les liaisons dangereuses, and his two films with director Pat O’Connor – A Month in the Country (1987) and Circle of Friends (1995) – were also praiseworthy.

But then came Pride and Prejudice (above), after which he became more widely sought after. While that led him into some roles that he might have been better advised to avoid – a view he has readily shared – it also provided the foundations for a substantial career.

His screen persona has allowed him plenty of room to move. He’s been found regularly playing put-upon English chaps, as in films such as The English Patient (1996), Shakespeare in Love (1998), Love, Actually and Hope Springs (both 2003), Easy Virtue (2008), The King’s Speech (2010) – where he redeploys the stammer he’d used to such good effect in A Month in the Country, except that this time it helped him win an Oscar – and The Railway Man (2013). He’s also been a strong romantic lead in The Girl with a Pearl Earring (2003) and the Bridget Jones films (2001, 2004 and 2016), where he plays another Mr. Darcy.

He’s played dashing Dads in What a Girl Wants (2003) and Nanny McPhee (2005). And for the Mamma Mia! films (2008 and 2018), he’s even dared to sing. Arguably, though, two of his most distinctive performances were playing grief-stricken men in Michael Winterbottom’s Genova (2008) and US fashion designer Tom Ford’s directorial debut, A Single Man (2009), the latter earning him an Oscar nomination. And a third, Supernova (2020), partners him with Stanley Tucci as a gay man dealing with his partner’s slide into dementia.

|

| Firth, Essie Davis, The Girl with the Pearl Earring |

When I spoke to him by phone in April, 2004, he was in Rome where he’d gone to promote the release of The Girl with the Pearl Earring. Reluctantly doing what actors are expected to do these days, he was playing the marketing game. While he’d prefer never to “do press”, as he puts it, he found himself doing just that.

Before we spoke, I’d been negotiating with the PR person assigned to look after him about how long the interview was to be. She’d understood it was to be 10 minutes; I’d believed it was going to be 30.

********************

TR: Hello.

Colin Firth: Hello. Apparently we’ve got 17 minutes. [Laughter. Unbeknown to me he’d been listening]

What’s the weather like in Rome today?

It’s pissing with rain. Like a Norfolk winter rather than an Italian one though. Dark and gloomy.

Apart from the weather and a publicist with a watch, what’s it like there?

[Laughter] Actually she’s not by me as we speak. I’m sitting in a barren room that looks like an interrogation room in a Belgrade police station. I’ve got some books on a shelf on the wall. If I look out the window, however, I’m looking at a beautiful terra cotta-tiled roof with a million TV aerials and a dome, of the mini-St. Peter’s variety. And beyond that I can see an ancient Roman palace and to my right there’s a statue of St. Peter. I’m high up, so I’m overlooking the rooftops.

When you were making The Girl with the Pearl Earring, did you get an inkling at any stage about whether or not it was going to be any good?

I always get lots of inklings, but their accuracy rate is not brilliant. So the honest answer is no, not an accurate inkling. Over the years, I’ve finished a day’s shooting thinking, ‘You know what. I have an inkling that we’re doing Something here. There’s something good happening.’

What are the signs?

It’s purely instinctive and intangible. You sometimes just feel that you’ve done good work, or something gels and you’ve developed this trust for the process and the director. And then another day it all seems to jar and nothing comes together. I usually withhold judgment now because I’ve been wrong so many times and it depends on so many variables and so many people.

I always think that it’s a miracle that a film ever gets made, given that there are so many different elements it depends on. The pre-production’s gotta be right, the script’s gotta be well-judged, and it’s gotta be well-interpreted by people doing more jobs than I could list. And then it’s gotta survive post-production and editing. It’s gotta have the right music choices, it’s gotta have the right pace, and then it’s gotta be marketed right. And if it gets through all of those, then you’ve got a success.

So that’s why it’s hard to have an instinct. You can have an instinct that you may be doing your own work well, but you’re in the hands of so many others. And on the other hand, you could be doing your own work pretty badly – that’s happened to me many times – but you’re saved by others.

|

| Firth, Renee Zellweger, Hugh Grant, the leads of Bridget Jones Diary |

I’d like to chase you more on that, but let’s move on. Is Helen Fielding’s account of her interview with you in the second Bridget Jones book an accurate rendering of your exchange?

Yes, it is, although it was contrived a little. You know, Helen is not Bridget and I’m not really Colin Firth, or at least not the one in the book. That’s someone I became for the interview. I thought it would be funnier if I took on the persona of a slightly different, rather serious actor who has no real patience for this woman.

And that’s not you at all?

Not really. [Laughs] I’m as silly as she is really. When we met… She really did come to Rome. I mean, she uses the reality as a kind of frame for the interview. But we had lunch as Colin and Helen, you know, and walked around Rome. And she describes a bit of that, but when we sat down to do the interview and she switched the tape recorder on, we both slipped into character.

|

| Firth, Renee Zellweger, Bridget Jones Diary (2001) |

It’s very funny.

And then we edited afterwards. She was generous enough to include me in that process. She would fax me a draft and I would say, “Maybe cut this or add that or change the answer here or there”. So we continued the contrivance for the next week or two. But it’s basically very much as it was given that we’re both inside our roles.

If you’re playing Mark Darcy in the screen adaptation of the book, who’s playing Colin Firth?

We don’t have that scene.

Oh no.

Actually, I shouldn’t have said that. It’s a trade secret. I’m in this rather paradoxical position of being told not to reveal too much about the film. But we’ve been performing in front of the world’s paparazzi and there’ve been press leakages for the last four months, so I think my silence is futile. [Laughter]

But if it hadn’t been left out, who would you have liked to play you?

Um. I can’t think of anybody glamorous enough really. [Laughter] I think I would have demanded the most impossibly glamorous human being that could be found. Nobody older than Orlando Bloom…

[Laughter] That was my teenage daughter’s suggestion over dinner this evening.

[Laughter] Very good. Well there you are. It would have to be Orlando Bloom or Justin Timberlake, somebody like that.

Well my wife came up with Hugh Jackman.

No, uncomfortably close. His woollen britches. I wouldn’t want him anywhere near me.

Have you ever played any characters that resemble you as you see yourself, or as you’d like to be?

No, actually. The second part of that question is a little more complex. But none of them are me as I see myself.

Right.

They probably all are representative of me to some extent. I think they have to be for any actor playing any role. For it to be convincing, it’s got to come from somewhere that’s you. Um, the question is about realigning the relevant parts of yourself for the role. As I’d like to be? Not really. I wouldn’t mind Mr Darcy’s castle, you know. There are details that you take a fancy to.

But you always find a hook on a character that you have to like about him. I mean, you can be playing the most despicable human being and if you pronounce them despicable then you’re gonna be so judgmental of the character that you won’t be able to make it real. In order to flesh something out, your job is to justify the character. So you always have to end up liking whoever it is.

|

| Rupert Everett, Firth, Another Country (1984) |

I’ve actually played unappealing characters and I’ve so convinced myself of the characters’ position that I get defensive if anyone says they’re unappealing. So I think you become very subjective. I think almost all actors would do that.

Well, for you then is acting becoming the character or playing the character?

Well, it’s a bit of both. When you say “becoming the character”, you don’t want to get psychotic about it.

Method “becoming”.

Yes. I had a Method training. And either becoming the character or letting the character become you, you know, it’s….. I do believe in getting to the heart of it and feeling that if you are that character and suspending disbelief…. It’s almost an infantile position, something that children do effortlessly. They can put themselves in a fantasy world. But they’re not psychotic, you know. The child can believe he’s a fireman or an astronaut. But Mum calls him for dinner, and he snaps out of it. Or not. But he’s got an eye on the real world.

I think there’s a danger that actors lose that. They talk about Bela Lugosi having insisted on being buried in his Dracula gear, ’cause he’s kind of lost the plot. I think if the actor’s unstable enough, it could get a little weird.

|

| Firth, Kenneth Branagh, A Month in the Country (1987) |

So there’s no danger of you going to your grave as Mr Darcy?

Well, I think others would probably quite happily see me go to my grave as Mr. Darcy. [Laughter] But I’d be quite happy never to see a pair of britches and a frilly shirt again. But, no… You do suspend disbelief but then you keep a sensible third eye open. You’ve got to have a critical view of what you’re doing as well.

I’ve read, and what you say indicates it, that you’ve found it difficult to escape the legacy of Fitzwilliam Darcy? Do you really want to? I mean, the words “meal ticket” come to mind?

Not really. No. I was kidding before really. You know, it’s not my problem escaping it. It’s other people and their perception of me. If it doesn’t bother them, it doesn’t bother me. The tag hasn’t hurt me in any way. It’s kept me known, it’s kept people interested. It’s something for people to write about, and it is mostly what they do write. And I don’t really care.

After a long day of press, the repetition of the question gets a little dull. But it’s no worse than that and I don’t spend a lot of time doing press. So, you know, I don’t have to deal with it at home, I don’t deal with it much in the street, and I’ve managed to keep the roles varied enough to keep me interested. So it hasn’t hurt much really. I think it’s probably kept me employed.

***************************

Editor's Note: This is a first part of an interview with the actor Colin Firth. It was recorded by Melbourne film critic Tom Ryan as the basis of a feature article for The Age. Previous posts in this series have been devoted to conversations with Lawrence Kasdan (Part One), Lawrence Kasdan (Part Two) Costa-Gavras Jonathan Demme (Part One) Jonathan Demme (Part Two) Click on the names to read the earlier pieces

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.