|

| Ken Russell |

ELGAR AND AFTER.

“Two roads diverged in a wood,” wrote Robert Frost, “and I took the one less traveled by,/And that has made all the difference.” But for him, as for most of us, the perception of that event as life-altering came afterwards.He talks of “telling this with a sigh/ Somewhere ages and ages hence.”

So perhaps I’m deluded that seeing Ken Russell’s Elgar, in less than an hour changed my life. But the conviction stubbornly resists correction.

Sixty years have not dimmed the memory of arriving home on a Sunday evening in the early nineteen-sixties (not from a movie, however, since the wowsers who ruled Australia still forbade Sabbath screenings) to turn the television to the channel which was running a series of new American documentaries.

Did the channel even know what it was showing? Based on its ramshackle choice of feature films, this seemed doubtful. Just as the vaguely-titled Midnight Movie could screen, consecutively, half a dozen Billy Wilder or Preston Sturges films in the same week, the bored technician shoving a 16mm print into the telecine that night had no idea he was introducing Australia to cinema verité.

Since titles were sometimes changed, we had to wait for the credits to know whose work we were watching. But the same names kept appearing: Richard Leacock, D.A. Pennebaker, Albert Maysles, James Lipscombe, Robert Drew. We’d already seen Primary, following John Kennedy on the campaign trail, Jane, about the stage debut of Jane Fonda, and Mooneyvs Fowle, detailing the rivalry of two high-school football coaches.

What would it be this Sunday?The Chair, about the fight to save a convict writer from electrocution? Maybe we’d follow race driver Eddie Sachs through the Indianapolis 500 in On the Pole? Or celebrate jazz vocal trio Lambert, Hendricks and Ross?

To my disappointment, it was none of these. Instead, the retrospective ceased as abruptly as it began. American films were supplanted by a British one and, moreover, from the BBC, that byword for the conventional. Instead of the topical products of Drew, Leacock and Pennebaker, it delved into the life of that most Victorian of composers, Edward Elgar.

|

| Elgar as a boy, riding a pony to the summit of the Malvern Hills Elgar (Ken Russell, 1962) |

I poured a beer and sat down, resigned to disappointment. Fifty minutes later, the beer, undrunk, was flat and my life forever changed. That, within the decade, I would move to London, almost immediately meet Russell and write his biography, became, in my perception at least, foregone conclusions.

What about Elgar made me so certain? It helped that the affinities Russell felt for the composer, in particular his Catholicism and working class background, were also mine. As well, I recognised in Elgar’s music and Russell’s visual imagination echoes of my own enthusiasms. When he said “I’m eaten up with the image: with the way things look!”, I knew in an instant what he meant.

As I was to discover, the first wonder of Elgar is that it was made at all. A few years after that first screening, a producer from the Canadian National Film Board, David Bairstow, would suggest to an audience of Australian documentary film-makers that the best way to approach making any film was to assume that it was impossible. But even the most Draconian of rules has its minute exception, and it was within this narrow margin that they must resign themselves to working. It was, and remains, one of the best pieces of good sense anyone has ever pronounced on film-making.

|

| Huw Wheldon, Ken Russell, 1962 |

In 1962, Russell confronted the weight of documentary tradition as laid down by John Grierson. He had only just overturned the rule that no actuality film must ever use actors; to do so made it a drama. Under his pressure, Huw Wheldon, producer of the Monitor series, grudgingly agreed he could show the composer Prokofief as a pair of piano-playing hands and a reflection in a pool – “but it must be a murky pool, mind you!” With the camel’s nose now in the tent, Wheldon accepted that actors might portray Elgar, but with few close-ups, and, naturally, in silence.

This suited Russell, who always preferred showing what people did to recording what they said. If words were needed, Wheldon supplied them. He wrote the commentary, and spoke its eloquently simple text in his famously resonant voice. Russell matched it with images that became inextricably entwined with the vision of the composer; Elgar as a boy, riding a pony to the summit of the Malvern Hills that look out over an unspoiled British countryside; an adult Elgar strolling through a field of wheat with his new wife, mind filled with the delirious music of the Enigma Variations; Elgar composing by lamplight while his wife, with pen and ink, ruled the music paper which they were too poor to buy.

|

| ",,,restraint was not among them..." Russell directing The Devils |

Ken had many sterling qualities but restraint was not among them. “If he wanted to shoot from the fifteenth floor,” Wheldon explained, “then you carried the camera and all the equipment to the fifteenth floor. And of course you used the stairs!” He invariably leapt before he thought, never more so than when, to convey Elgar’s disgust with the jingoistic employment of Land of Hope and Glory as a recruiting tool, he used it over newsreel footage of blinded soldiers in a stumbling crocodile, each with a hand on the shoulder of the man in front. It created a furore, which Ken claimed to find incomprehensible - as had Orson Welles with his War of the Worlds broadcast. (“People really believed Martians had landed? You can’t be serious.”)

In 2002 the flagship arts program The South Bank Show invited Russell to take a look back at the film and Elgar in general. Producer/presenter Melvyn Bragg was a sufficiently old friend to put down his foot about content, so there’s no hint of Lisztomania or The Devils. Instead Fantasy of a Composer on a Bicycle recaptures some of the first film’s charm and antique style. The actors are silent and Russell’s own commentary sparse. Instead, fairies dance among the giant beeches of a British forest and three bandaged soldiers and their nurse perform a string quartet on themes of Pomp and Circumstance. Finally, Elgar, upright and Edwardian in bushy moustache and tweeds, bikes around the home town that his fame has made a tourist Mecca before solemnly pedalling down the high Gothic nave of stately Worcester cathedral.

Technological advances have not invalidated Bairstow’s thesis about the impossibility of making actuality films. It may be physically easier today, but the number of those able to do so remains stubbornly minute. Talking heads predominate, not often speaking much sense. Recreated reality seldom achieves any feeling for the past. Cinema verité has become the TV news but, oblivious to its lessons, amateurs using cell phones to document an event still hosepipe about like 8mm home movie makers of half a century ago. Russell, thou shouldst be living at this hour. Cinema has need of thee.

The 1962 film, with an introduction is HERE ON YOUTUBE

The discussion with Melvyn Bragg is HERE ON YOUTUBE

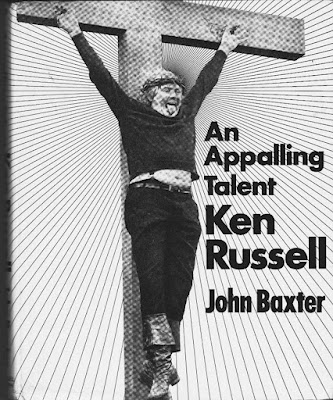

John Baxter's book, cover below, is offered for sale HERE AT BADGER BOOKS OF WOOLLAHRA and HERE ON EBAY

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.