It’s the time of year when magazines and newspapers around the globe haul out their lists of recommended Yuletide films, occasionally stumbling across something made before 1990 (other than It’s a Wonderful Life or Meet Me In St. Louis). I’m sure you’re familiar with most of them, but there’s one that you’ve probably never heard of, made in 1947, the year after Capra’s classic, three years after Minnelli’s, and it’s certainly worth a look.

Adapted from stories by Laurence Stallings, Richard Landau and, uncredited, Arch Oboler, Christmas Eve is an unexpectedly appealing family reunion frolic written by Stallings, Landau and, also uncredited, Robert Altman… Yes, the Robert Altman. It wasn’t his first involvement in the film business: he’d worked as an extra on The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, which was shot in 1946 and released in mid-1947 a month or so before Christmas Eve. Apparently, his input stretched only as far as a contribution to the storyline, one sufficiently minor to deny him an on-screen credit.

The film’s plot is routine Christmastime fare: a rich old woman; an avaricious nephew; the three adult foster sons who’ve asked nothing of her and, for better or worse, gone their own way in the world; the looming Christmas Eve that she hopes will bring them to her home in New York City.

We first see Matilda Reed (Anne Harding, above) at her window, nervously peering at the limousine that’s pulled up at her door. Her nephew, Phillip Hastings (Reginald Denny), has summoned Judge Alston (Clarence Kolb) to have her declared incapable of looking after her own affairs and the good judge – as he eventually turns out to be – is about to meet her. Phillip feigns affection: “She’s such a lovely old heirloom, despite her eccentricities,” he says. His real concern is that she’s about to pass her vast wealth on to the three orphans she’d adopted years before and whom she has employed a private detective (Joe Sawyer) to track down. Now they’re fully grown men: George Brent plays Michael, George Raft is Mario and Randolph Scott gets third billing as Jonathan. However, the more we see of Matilda, the clearer it becomes that she’s very well-equipped to deal with her own affairs and has the measure of her wretched nephew.

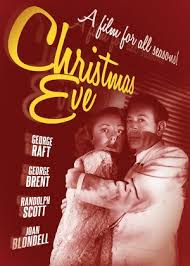

|

| George Brent, Joan Blondell |

The film unfolds in three parts with an unofficial prologue – the introductory scenes described above – and epilogue. Each part introduces a brother: Michael is a playboy who has his own money issues and a girlfriend (Joan Blondell) who doesn’t take any nonsense from him; Mario is a gangster living in South America, where his girlfriend, Claire (Virginia Field), has caused him to get mixed up in the nefarious affairs of a Nazi (Konstantin Shayne); and Jonathan, “Johnny”, is an aw-shucks rodeo rider who goes by the name of the Pendleton Kid and who turns out to be a lot smarter than he initially appears.

Brent and Raft play it more or less straight, but, in perhaps his best collaboration with journeyman director Edwin L. Marin, Scott delivers an accomplished comic performance, simultaneously oozing charm and knowingly sending up his man-of-the-West persona. When he arrives at Grand Central Station, he’s met by Matilda’s manservant, Williams (Dennis Hoey), but is much more interested in the attractive woman, Jean (Dolores Moran), who’s eyeing him off in the background.

|

| Randolph Scott, Dolores Moran |

In a delightfully wacky side-story, she turns out to be a welfare officer investigating an adoption racket and sees Johnny as a likely candidate to play her husband when she visits the home of a suspect, Dr. Bunyan (Douglass Dumbrille). “I picked you out because you look the part of a big, tender-hearted hero,” she explains, and she’s called it right. He does, and he’s only too happy to give himself over to the undercover operation, Scott eagerly seizing the opportunity to play it all for laughs.

When Dr. Bunyan expresses doubts about this couple who’ve arrived on his doorstep, cowpoke Johnny mock-threateningly pulls a gun and tells him, “We’d like to look at some of your yearlings.” To Jean, he then says, “C’mon, honey. Let’s go to the corral and look at his stock,” offering the good doctor an irresistible deal: “A hundred white-faced heifers for one little pink-faced calf.”

When he and Jean make their way to the doctor’s nursery, they find three (gorgeous) babies awaiting them. “Why, it’s time you were weaned and given the run o’ the range,” he says to one of them. “Any reduction if I take the whole herd at the rail-head?” he asks. And when Bunyan explains that he’ll need to see proper adoption papers before he does anything more, Johnny asserts himself: “Why? I haven’t seen a brand on any of them.”

This segment of the film is its best, written and played in a winning screwball mode and confirming that Scott, had he chosen to look beyond Westerns for his future, was perfectly able to fit comfortably into the fast-talking, wise-cracking romantic comedies that were just as popular as Westerns in Hollywood during the 1940s. He and Moran are terrific together and there’s none of the awkwardness with women that seemed endemic to the roles he played in Westerns.

|

| George Raft |

Bizarrely, of the trio playing her adopted sons, only Brent (43) was younger than Harding (45) when the film was made. Both Scott (48) and Raft (46) were older. And Reginald Denny (56), playing her nephew, was born a decade before her. The film was Scott’s third (out of nine) with the prolific Marin, who was to die five years later at the age of 52 after a 20-year career in which he made more than 50 features.

Christmas Eve was remade for television in 1986 by director Stuart Cooper, with a cast led by Loretta Young (in the role played by Anne Harding, the character renamed Amanda Kingsley), Arthur Hill (as her only son, Andrew, the equivalent of the original’s nephew), and Ron Leibman (as the private investigator on the case). Based again in New York City, and written by Blanche Hanalis, who adapted Little House on the Prairie for TV, the telefilm also gives her (along with the official writers of the original) a “story by” credit.

Earnest and terribly mushy, the remake keeps an approximation of the general structure of the story – although this time the matriarch is trying to track down a trio of grandchildren rather than adoptees – but conjures up entirely different back-stories for them. Here they’re two young men – a musician based in Nashville (Patrick Cassidy, David’s brother) and a draft dodger now living in Canada (Charles Frank) – and their sister, a teacher in Los Angeles (Season Hubley).

However, the film spends very little time with them, beyond establishing that they’re apparently irretrievably estranged from their father. The focus is instead primarily on Amanda Kingsley’s situation as her son tries to take charge of her fortune by having her declared incapable of looking after her own affairs. Adding injury to this insult, she’s also diagnosed as having an aneurysm that could kill her soon and suddenly. What’s entirely missing is the playfulness of the original, the knowing wink that drives the telling of the story. The energy and the sense of fun that the cast, and Scott and Moran in particular, brought to Marin’s original have also gone missing and the film suffers from their absence.

The original Christmas Eve can be found on YouTube if you click here

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.