BASED ON A TRUE STORY

Those words at the start of a movie often give me some trepidation. Often it’s an explanation as to why the movie to follow lacks credibility, or as an excuse to throw any and everything into the action. So, when it does apply to a film and it does not claim that at the start, an end reveal can actually have an impact.

Two films I saw a couple of days apart made me think about how we relate to a movie ‘based on a true story.’ Both were screened in the current batch of film festivals, one the Russian Resurrection Festival, the other the Palace Cinemas Cine Latino Film Festival. And both were roughly contemporaneous in their period.

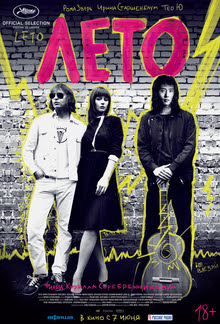

I saw the Russian film, Summer (poster, left) first. This is directed by Kirill Serebrennikov. The director has a Jewish father, a Ukrainian mother and since last year has been under house arrest, allowed no internet access and with other restrictions. Even so, he has kept working, and is currently trying to direct a new Mozart production for the Zurich Opera, by using USBs.

He also directed the excellent film, The Student (2016) about a high school student who feels the world has surrendered to evil, and starts challenging his teachers and all around him.

Summer, which was screened in Cannes this year, is set in the late 1980s in the Leningrad pop/rock/ would-be punk music scene, Mostly filmed in black and white scope, the main character is Victor Tsoi who becomes the protégé of an older musician Mike Naumenko. A triangle develops with Mike’s wife Natalia. This is not an unusual story – the fascination is the depiction of the music underground scene at this time in the Soviet Union when serious cracks were becoming visible in the culture, particularly with young people who were only too aware of a world outside.

Their prized possessions are LPs of Bob Dylan or the Rolling Stones or the Sex Pistols. There is one scene that so embodies the oldies attempts to repress young culture. We see an officially approved rock concert – of course the lyrics have been officially checked beforehand. The band is on stage, the audience – largely young girls in their nice twin sets – sits demurely in their seats. Big-bosomed babushkas prowl the aisles ready to eject anyone who dares to stand up or scream or in any way break decent behavior.

|

| Summer |

Until one of the musicians basically says, “Fuck this” and lets fly with a heavy thumping riff and mayhem breaks out. At last the girls in the audience are clearly enjoying themselves. Our visuals become scribbled over, graffiti fashion, madly adding another level of animated excitement, for the heavy rock number. (The film’s poster hints at the style which punctuates other exhilarating moments in the film.) Until a new title cuts us back to size, “This never happened.” We’re back in the reality of repressed rock.

This picture of Russian society at this moment is fascinating, and though it’s not my music scene I was intrigued by this story set against this important historical time. Then at the end, a coda has stills of both Victor and Mike, with their birth dates and dates for their deaths that are only a few year ahead of our film. We have in fact been watching a bio-pic of two people who did exist.

Now, a few articles have certainly cast doubt on how accurate it is, with one music critic calling it a lie from beginning to end. But this was not important to me, and perhaps as a result we have a more satisfying dramatic film, certainly a film with a lot of interesting things to say about this period near the end of the Communist regime. Would I have been as receptive if I’d thought I was seeing a rock music bio-pic?

The Cuban film, A Translator (poster left) takes place at much the same time. We meet our main protagonist taking his small son to see Gorbachev when he visited Cuba in 1989. Malin is a professor of Russian literature, until one day he and his colleagues arrive at the university to find notices on their offices saying that Russian classes have been cancelled until further notice. Malin is told to report to a large hospital, where he finds he has been assigned to be a translator for a large number of Russian children.

The Cuban film, A Translator (poster left) takes place at much the same time. We meet our main protagonist taking his small son to see Gorbachev when he visited Cuba in 1989. Malin is a professor of Russian literature, until one day he and his colleagues arrive at the university to find notices on their offices saying that Russian classes have been cancelled until further notice. Malin is told to report to a large hospital, where he finds he has been assigned to be a translator for a large number of Russian children.

These are in fact children who have been affected by the explosion at the Chernobyl reactor in 1986. Malin is resentful of this assignment. Moreover, the hours he now has to work impose strains in his domestic life where his wife has her own life curating a potentially important art show while also in the early stages of a potentially difficult pregnancy. Gradually, however, Malin sinks into his new role and discovers a sense of involvement and commitment with these children, encouraging them to write about their experiences. Or draw if they can’t write.

But outside the hospital the world is changing. The political and economic world is not the subject of this film, but it is there and its representation is one of the interesting things in A Translator. After Gorbachev’s visit, we hear reports of a change to arrangements where Cuba got Russian oil in exchange for its sugar. Now, who will buy Cuba’s sugar? Early on, we’d seen Malin and his small boy in a supermarket, well stocked with essentials and all those little extras like kids’ lollies or cakes. Next time he goes, shelves have about two or three cans of perhaps five or six different items. Petrol rationing soon stops completely – there is no petrol to ration.

This was not a great film, but one I enjoyed. The story of cold-hearted professor won over by the fates of sick children is not new, and perhaps not treated in any madly original way. And I couldn’t keep wondering why, if he was there to be a translator for children, wouldn’t he be more needed during the day than the night? Or was he given the night shift so there could be dramatic situations such as a conflict with his wife over picking up their son?

And then we get some screens at the end with extra information. After 1990, Cuba treated over 26,000 victims of Chernobyl, including about 1,000 annually between 1990 and 1995. I never knew that. Then we’re given some details about our protagonist in the period after movie’s end. Oh, yes. The marriage did break up. He went to Italy. She stayed in art curation.

Then the real surprise. Their two boys - Rodrigo and Sebastián Barriuso – grew up and directed this film about their father! Of course, I’d read this in the Festival blurb but forgotten it. And coming like this it was rather a bombshell. It probably doesn’t make the film a better piece of drama, but I certainly found myself in a different relationship with its story.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.