The

Night of Counting the Years is the second film to

be announced for Sydney's newest film festival, Cinema Reborn, taking

place at the AFTRS Theatre, Moore Park Entertainment Quarter, from 3-7 May

2018. Details of the first film to be announced can be found if you click here.

The complete program and details of subscription tickets will be released in

February 2018.

*

*

*

*

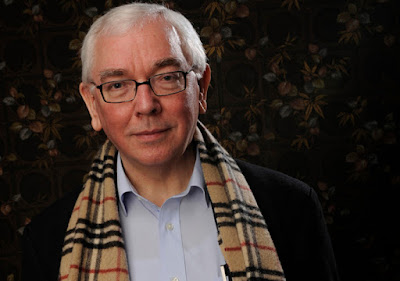

In 2013, the

Dubai Film Festival published the results of a poll from 475 critics, writers,

novelists and academics selecting the Best 100 Arab films of all time. At the

top of the list, as the greatest Arab film ever made, was The Night of Counting the Years (Momia), the only feature directed by Shadi Abdel

Salam and released in 1969.

|

| Shadi Abdel Salam |

After initial

festival screenings, it all but disappeared with only a few 16mm prints in

circulation. It was restored in 2009 by The Film

Foundation’s World Cinema Project at Cineteca di Bologna /L’Immagine Ritrovata

laboratory in association with the Egyptian Film Center. No Blu-ray or DVD

copies have been made from this restoration.

Martin Scorsese, the Chair of the World Cinema

Project writes about The Night of Counting the Years:

Momia

(The Night of Counting the Years), which is

commonly and rightfully acknowledged as one of the greatest Egyptian films ever

made, is based on a true story: in 1881, precious objects from the Tanite

dynasty started turning up for sale, and it was discovered that the Horabat

tribe had been secretly raiding the tombs of the Pharaohs in Thebes.

A rich theme, and an astonishing piece of

cinema. The picture was extremely difficult to see from the 70s onward. I

managed to screen a 16mm print which, like all the prints I’ve seen since, had

gone magenta. Yet I still found it an entrancing and oddly moving experience,

as did many others. I remember that Michael Powell was a great admirer.

Momia has

an extremely unusual tone – stately, poetic, with a powerful grasp of time and

the sadness it carries. The carefully measured pace, the almost ceremonial

movement of the camera, the desolate settings, the classical Arabic spoken on

the soundtrack, the unsettling score by the great Italian composer Mario

Nascimbene – they all work in perfect harmony and contribute to the feeling of

fateful inevitability.

Past and present, desecration and veneration,

the urge to conquer death and the acceptance that we, and all we know, will

turn to dust… a seemingly massive theme that the director, Shadi Abdel Salam,

somehow manages to address, even embody with his images. Are we obliged to

plunder our heritage and everything our ancestors have held sacred in order to

sustain ourselves for the present and the future? What exactly is our debt to

the past?

The picture has a sense of history like no

other, and it’s not at all surprising that Roberto Rossellini agreed to lend

his name to the project after reading the script. And in the end, the film is

strangely, even hauntingly consoling – the eternal burial, the final understanding

of who and what we are… I am very excited that Shadi Abdel Salam’s masterpiece

has been restored to original splendor.

–Martin Scorsese, May 2009

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

The restoration of Al

Momia used the original 35mm camera and sound negatives preserved at

the Egyptian Film Center in Giza. The digital restoration produced a new 35mm

inter-negative.

CONTACT US: If you would like to receive advice about film selections, schedules and other news relating to Cinema Reborn (3-7 May, 2018) send an email to filmalert101@gmail.com or check in at the Cinema Reborn website