The Ranown Cycle, Part 1

Beginning with Western Union (1941), Randolph Scott and producer Harry Joe Brown worked together on 19 films under the banner of their production company, Scott-Brown Productions (1). Ranown Pictures Corp., named after Scott and Brown – “Ran” as in Randolph, “own” as in Brown – made three films, all produced by Brown, and starring Scott, who is also credited on one (1955’s Ten Wanted Men) as associate producer.

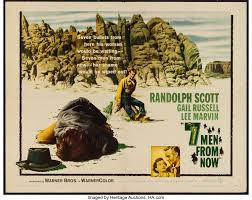

Simple? Perhaps. But then it starts to get complicated. The Ranown Cycle, as it’s become known, was made up of half a dozen films starring Scott and directed by Budd Boetticher. The first was Seven Men from Now (1956), produced by Andrew V. McLaglen and Robert E. Morrison for John Wayne’s company, Batjac. Brown produced three of the following five and was executive producer on the other two, with Scott credited as associate producer on three.

|

| Budd Boetticher |

The cycle might be named after the two men, but it’s Boetticher’s pure, poetic vision that drives them, supported by a terrific repertory company that included two screenwriters (Burt Kennedy and Charles Lang), three cinematographers (William H. Clothier, Charles Lawton, Jr., and Lucien Ballard), Scott in six career-defining performances, and a superlative team of supporting actors (with Lee Marvin, Gail Russell, Richard Boone, Maureen O’Sullivan, Arthur Hunnicutt, Karen Steele, Noah Beery, Jr., Craig Stevens, L.Q. Jones, Pernell Roberts, Lee Van Cleef, James Coburn, Nancy Gates, Claude Akins and Skip Homeier among them).

Despite Brown’s non-involvement with Seven Men from Now, it’s still included in most discussions of the cycle. Boetticher also worked on one other film starring Scott (Westboundin 1959), produced for Warner Bros. by Henry Blanke, but it’s generally not deemed to belong in the same company as the others.

|

| Harry Joe Brown |

However, the six films officially included in the unofficial cycle make up one of the finest runs in Hollywood’s history, even though they’re generally categorised as B-movies because of their running-times (between 74 and 78 minutes), their low budgets, their production schedules and the way in which they were programmed at most cinemas on their initial release. Through them, Boetticher built a unit of actors that gave texture to their worlds and developed a modus operandi that has resulted in six true treasures of American cinema. If readers of Film Alert aren’t familiar with the Ranown cycle, now might be a good time to discover it

Over the coming weeks, by way of designing something of a guide, I will deal in order with each of the six films of the cycle.

Seven Men from Now (Budd Boetticher, 1956)

“It was the beginning of a beautiful filmmaking relationship.

(Sean Axmaker re. the meeting of Boetticher, Scott and Kennedy, 2006) (2)

Made by John Wayne’s Batjac Productions for distribution by Warner Bros., Seven Men from Nowis the first of the four Boetticher/Burt Kennedy collaborations that star Randolph Scott and the first of seven films Boetticher made with the actor. However, it might never have happened that way at all. According to Kennedy (3), it wasn’t until Robert Mitchum expressed interest that Wayne discovered the merits of Kennedy’s script and called on Boetticher to become involved.

Wayne himself was originally set to play the Scott role until a timing clash loomed with The Searchers and the actor-producer turned to Scott to replace him… eventually. Gary Cooper was first offered the role and Joel McCrea and Robert Preston were also considered. Apparently Batjac’s initial reaction was to dump the project entirely when Wayne became unavailable, until the company learned that, given the amount already spent on pre-production, it would be more economical to press ahead.

|

| Randolph Scott, Seven Men from Now |

The plot lays the foundations for several of the Boetticher/Scott films to come, not all of them written by Kennedy. All of Scott’s characters in the Ranown cycle are dealing with a troubled past, sometimes to do with the loss of their wives, leading to their vengeful pursuit of those responsible.

Here, we discover about a third of the way into the film’s taut 78-minute running-time that the wife of former sheriff Ben Stride (Scott) had been killed in a hold-up in Silver Springs. His mission is to find those responsible and execute them, he’s single-minded in his search for them, and he follows the money trail to find them.

However, he also blames himself for her death, for failing at what he later describes as “a man’s job”, the one that requires him to look after his woman. Six months earlier, he’d lost his position as sheriff in Silver Springs and his pride had led him to refuse the job of deputy, thus forcing her into the workplace to keep them financially afloat. He reasons that, if she hadn’t been working in the stagecoach office, she wouldn’t be dead.

The film opens with a night-time scene during a storm. Stride enters the frame with his back to the camera, a dark knight with a mission. He’s immediately established as a force of disruption, interrupting two men sitting by a small campfire, the subsequent exchange also establishing him as a man of few words and decisive action. Asked by one of the men if any of the Silver Springs killers have been found, he replies, “Two of ’em,” before gunfire erupts and the men die offscreen.

Later, he encounters a couple from the east, John Greer (Walter Reed) and his wife, Annie (Gail Russell), whose wagon has been bogged in the mud. In his matter-of-fact way, he sets about helping them and, since, like him, they’re headed south – him to Flora Vista, they planning on eventually turning west towards California – he agrees to ride with them.

Again, though, he’s a force of disruption. As he and Greer wash down the horses in the river in an appealingly lyrical aside, and Greer prattles on about his life, Stride remains largely silent, his attention distracted by Annie who’s bathing downriver.

|

| Gail Russell, Seven Men from Now |

At this point, he’s simply a mysterious traveller: we have yet to learn about his wife. But his exchanges with Annie and the glances they share speak of a mutual attraction. In retrospect, after we’ve learned about his wife’s death, it’s perhaps that Annie is also reminding him of something he’s lost. But, even though their feelings remain unspoken throughout – he never calls her anything other than “Mrs. Greer” – their interactions create a potent sexual tension that remains unresolved, even at the end.

Alongside this and by way of contrast is the lasciviousness of the film’s chief villain, Bill Masters (a wonderful, sometimes Iago-like performance by Lee Marvin). His leering looks and innuendo-laden dialogue as he harasses Annie and teases Stride constitute the antithesis of the Scott character’s clipped conversation and straight-faced righteousness. Masters makes no secret of the fact that he’s just as interested in tracking down the men whom Stride is pursuing as the former lawman is. The difference lies in how the two men regard the $20,000 the killers have stolen. For Stride, the money is only a means to an end – when he finds the money, he’ll find the men – whereas for Masters it’s an end in itself.

|

| Lee Marvin, Seven Men from Now |

In Seven Men from Now, Boetticher makes Scott’s character his own, just as John Ford makes Wayne’s westerners his own in films from She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949) through The Searchers (1956) to The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962). Setting him against Marvin’s charismatically sociopathic villain – just as Ford contrasts Marvin and Wayne in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance – Boetticher deploys Scott’s iconic stature to make Stride not just an upright moral force who inhabits an isolated space outside the law but also a deeply troubled and seriously flawed human being. Like Wayne’s Ethan Edwards, he doesn’t really fit in the civilized world or any other socialised future.

In pursuing his mission of vengeance it’s as if he excommunicates himself from the possibility of belonging to a community. At the end, after one part of his mission has been accomplished and as he heads back to Silver Springs to take on the role of deputy sheriff that he’d formerly refused, it seems that the other part of his mission – dealing with his own guilt about his wife’s death – remains unresolved. The journey is only half over. Will his self-imposed penance allow him to forgive himself or has his inability to let go of his obsession doomed him, like Ethan, to wander forever between the winds?

|

| Scott, Marvin, the final shootout, Seven Men from Now |

He farewells the now-widowed Annie as they stand by the stagecoach she’s planning to take to California, inviting her to visit if she’s ever anywhere near Silver Springs. His yearning for her is clear, but it’s been crushed by the repression of his own feelings, by his displacement from any sense of belonging to her or to the community that she represents.

There is a deeply moving sadness at the heart of Seven Men from Now, as there is in The Searchers: it’s to do with the plight of a man who’s trapped by his impulses and helpless to escape from them. Screenwriter Robert Towne (Chinatown,The Yakuza), in the extras on the DVD disc, accurately refers to the “courtliness” that is a part of Stride’s personality, but it’s also a quality that remains a part of his aloofness from emotional contacts rather than an attribute that enables him to engage intimately with others.

After Stride has gone, Annie’s reaction to his half-invitation is to cancel her ticket to California and to announce that she might stay in town for a little while longer. For her, there’s still a possibility of a future with Stride and the film indeed allows that there might be. But, at the same time, one gets the sense that the course that Stride has determined for himself has cast him as a lost soul.

In Seven Men from Now, Boetticher finds a context in which Scott’s inward-looking persona becomes much more than the detached force of righteousness that drove the characters he played in so many previous Westerns. Stride can avenge himself on the men who’ve killed his wife, but there’s nothing he can do to erase the guilt he feels for what happened to her. He is, as Jim Kitses puts it in his brilliant commentary on the DVD disc, like “the craggy landscape” he passes through (4). And he is far more at home in it than he is in constrained settings – like the interior of the Greers’ wagon, or the town of Flora Vista. This is another of those great Westerns in which the circumstances in which the protagonist finds himself, and which lead to him riding off alone at the end, go beyond clichés to become human tragedies.

(1) See http://filmalert101.blogspot.com/2020/09/streaming-on-youtube-tom-ryan-revives.html

(2) Sean Axmaker, http://sensesofcinema.com/2006/dvd/seven_men_from_now/

(May, 2006)

(3) C. Courtney Joyner, The Westerners: Interviews with Actors, Writers, Directors and Producers, McFarland & Co., Inc., USA, 2009, p. 131

(4) Intriguingly, Kitses’ commentary makes mention of two projected but eventually aborted remakes of Seven Men from Now. One was to have starred Arnold Schwarzenegger, but it eventually turned into the similar-but-different Collateral Damage (2002). The other, by Paul Schrader, was titled Nine Men from Now and was, apparently, to have been shot in the mountains in Mexico.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.