CLOUDLAND REVISITED REVISITED.

|

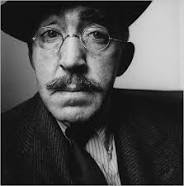

| S J Perelman |

The cinema in the country town where I was raised screened only at nights, so I first experienced this particular distraction vicariously, via a series of articles in The New Yorker called Cloudland Revisited and written by the incomparable S.J. Perelman.

If anyone knows Perelman’s name today, it’s probably as the Marx Brothers’ screenwriter on Monkey Business and Horse Feathers, which is rather like celebrating Albert Einstein for his skill on the violin. (Perelman once excused his Hollywood experiences as “No worse than playing piano in a whorehouse.”) He manipulated the English language with an acrobatic skill that, from an early age, left me breathless. As Dorothy Parker wrote in the introduction to The Most of S.J. Perelman, the bulky anthology a copy of which I wore to tatters as bedside reading throughout adolescence, “before they made S.J. Perelman, they broke the mould.”

In the late nineteen-forties and early nineteen-fifties, Perelman took his scalpel to a dozen novels popular during his childhood, ranging from Tarzan of the Apes to The Sheik. He then turned his attention to silent movies; specifically those shown in afternoons at the Museum of Modern Art. Among the titles to appear in his crosshairs were A Fool There Was and Foolish Wives.

|

| Erich Von Stroheim |

Perelman’s masterwork of demolition is probably The Wickedest Woman in Larchmont, which skewered – you see, he has me doing it – the 1915 melodrama A Fool There Was, a production so dire that no director would take credit. (Frank Powell was the guilty party.) Perelman dismissed the film as a whole but was mesmerised by the girl playing a character identified only as The Vampire. Born Theodosia Goodman, she made her name under the pseudonym Theda Bara – an anagram, it was pointed out, of “Arab Death.” For her, Perelman rolled out the big guns.

|

| Theda Bara |

(I remember feeling smug at not having to look up “nonpareils”, since my father, a baker, used these multi-coloured sugar beads, known colloquially as “Hundreds and Thousands,” to decorate cakes. “Little Egypt” and “hoochie-coochie” took a little more research.) Once again, through the generosity of YouTube, we can view A Fool There Was in its seedy glory, and relish the sight of Ms. Goodman having her way with a variety of solid citizens, all of whom succumb to her peremptory demand “Kiss me, my fool!”

I never expected to meet Perelman, which made it all the more pleasurable, browsing one afternoon in New York’s Gotham Book Mart, to recognise the short man with the moustache standing next to me, searching among the books on cinema.

“Excuse me,” I stammered, “but are you...?”

These chance meetings seldom go beyond the polite exchange of banalities, but this was different. First, I was able to help him find the book he wanted: John Gregory Dunne’s The Studio, his account of a year spent watching such Twentieth Century-Fox productions such as Doctor Doolittle crash and burn. Second, I had enough of his bons mots by heart to quote some; in particular, his description of a Dutch businessman encountered in a voyage through the south seas. “My heart,” he said, “laying a moist strangler’s hand on the chest where that organ lurked.”

My bona fides established, we chatted for twenty minutes, a conversation of which I remember in particular his careful choice of words, even in such a casual situation. For example, Bert Lahr in his play The Beauty Part was “protean”. He also explained the rag trade source of the title. (The “beauty part” of a dress is the front section on which style and decoration are concentrated.) And as, happily, there were a couple of his books on a nearby shelf, I had him inscribe both. I still remember the surprised look on the face of proprietor Francis Steloff (the portion one could see above his biblical white beard) as he cashed me out. “S. J. Perelman. The Ill-Tempered Clavichord. First edition. Inscribed by the author.....fifteen dollars?!!”

Sadly, Perelman’s is no longer one of those names which, dropped into conversation, evokes recognition, admiration, even delight. But I’m not the only one to have fallen under Perelman’s spell. The New Yorker’scurrent film critic, Anthony Lane, a self-confessed acolyte of P.G. Wodehouse, has an occasional turn of phrase in which I detect an echo of S.J. What can one say but abracadabrant, effulgent, even splendiferous?

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.