|

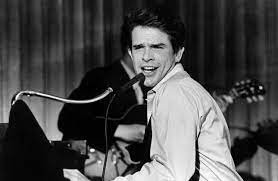

| Arthur Penn, Warren Beatty |

The series on the 60 years international of art cinema 1960-2020 by Bruce Hodsdon continues with the first essay on New Hollywood.

These notes are accompanied by a set of summary table and decadal lists of art film directors 1970-2020 (click to link) which contain 5 lists 1970-2020 including a list of women art film directors over the full 60 years from 1960),

The sixties is the subject of an on-going separately annotated listing of directors in part 6 divided by nation-states in multiple sections.

********************************************

Thomas Shatz identified three distinct decade-long phases in the emergence of so-called New Hollywood after the War: from 1946-55, from 1956-65, and from 1966-75 marked through these four decades by the shift to independent film production, the changing role of the studios, the take-off of commercial television, and changes in American lifestyle and media consumption. (Elsaesser 239-40 ref ch 18, fn3 end note p.361).

Arthur Penn (1922-2010) is perhaps the director who best typifies the new cinema of the 1960s. He came up through live television in the 50s and achieved success as a director in the theatre. Penn first went to Hollywood in 1956 where he made The Left-Handed Gun (1957) at Warners with Paul Newman only to have it taken from him for editing, later by chance seeing it playing in a New York cinema on the bottom half of a double bill. It nevertheless attracted positive critical attention, particularly in France. He was more successful directing the film of William Gibson's The Miracle Worker (1962) which he had earlier directed on television and to plaudits on the stage. What comes to the fore is the intense physicality of the central performances which transmutes in his subsequent films to “arguably the most complex and mature treatment of violence in the American cinema” (Wood 12).

|

| Paul Newman, The Left-Handed Gun |

Penn was replaced as director, at Burt Lancaster's insistence, after only one week on his first big budget film, The Train (1963). Then followed Mickey One (1964), Penn's personal 'Euro-American' art film. Despite its failure he saw it as an important transition in his stylistic and thematic development. The downward spiral continued with another critical and commercial failure, The Chase (1965), adapted by Lillian Hellman from a novel and play by Horton Foote. In his only extended experience of directing a major production in the mould of 'old Hollywood', Penn spoke of his complete bewilderment at the imposed daily re-writes of the script which culminated in producer, Sam Spiegel, re-editing and cutting 13 mins.

|

| Marlon Brando, The Chase |

Beatty’s persistence

Penn's fortunes in the industry dramatically reversed when Warren Beatty, who had played the lead in Mickey One, approached him about directing Bonnie and Clyde from a script by Robert Benton and David Newman, for which Beatty had secured the rights; they had earlier written it in the hope of interesting Godard or Truffaut to direct. Penn was initially reluctant, not much liking the script, but as a result of the strength of Beatty's persistence, finally agreed ( Biskind pp.26-36). Although Beatty considered Mickey One pretentious and affected he recognised Penn's talent. He had to fight for the film to be shot on location in Texas “far from the heavy hand of the studio.” Beatty may have had misgivings along the way, none more so than when the script was in trouble or crucially at the final hurdle when the studio was massively short changing the film's release in the US.

|

| Warren Beatty, Mickey One |

Beatty's persistence was born of a need for a career success and with Bonnie and Clyde he became, “if not necessarily an auteur, one of the most powerful figures in the industry” (49). Estelle Parsons related to Biskind how Beatty and Penn “argued over every shot,” with the film's script doctor Robert Towne acting as a buffer. Benton and Newman, Beatty and Penn did, however, all agree “that the violence should shock.” Penn explained that they would not be repeating what the studios had done for so long: “that you couldn't shoot somebody and see them hit in the same frame” (34-5).

|

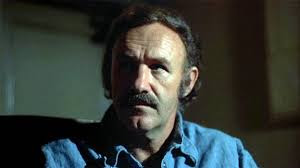

| David Newman, Robert Benton |

Bonnie and Clyde marked a turning point in the editing of feature films. Much of the action is perceived from Clyde Barrow's point of view, his subjectivity, and that of Bonnie Parker, coming to dominate. Dede Allen's fast cutting requiring careful layering to avoid viewer confusion. In a manner influenced by French new wave directors, most notably early Godard and Truffaut, establishing shots were dispensed with through the film, abrupt cuts to angled shots and close-ups replacing conventionally ordered establishing cut-ins and fade outs for entering and leaving scenes. This was central to Penn's intention of eliminating the clear-cut distinction between the good guys and the bad guys while it was also central to Beatty's concept of creating a visually distinctive “new American cinema.” It was soon widely adopted in Hollywood but generally without the underlying artistic intent of Allen and Penn to reorient viewers' relationship with the characters. At the same time Dede Allen denied that it constituted a New York based “Dede Allen” school of editing, joking that it was really an “Arthur Penn” school because he shot so much footage that she required several assistants to handle it (Monaco 90-2).

|

| Faye Dunaway, Warren Beatty, Bonnie and Clyde |

The pleasure of pulling this account together is the uncovering and testing of one's past intuitions on key films now overlaid by the memories of countless other movies, buttressed by claims of frequently enshrined auteur credentials. It involves reviewing a benchmark film like Bonnie and Clyde which then seemed to confirm what we felt about Penn's talent revealed on the first viewing of The Left-Handed Gun at a mid-week suburban 'ranch night' in the mid sixties. This has been supplemented by turning up reviews and interviews in the likes of 'Sight & Sound' and 'Movie', the latter most notably bringing the serious weight of retrospective reflection to the auteur's body of work. The Left-Handed Gun and Night Moves both have the credentials for cinephilic recovery or revisionism, each being seen to have been stranded respectively by the indifference of the studio and dismissal or neglect by much of the critical establishment.

Kael’s defence

Bonnie and Clyde was a hit in London at the end of 1967 but the indifferent US run had finished following repeated attacks by Bosley Crowther in the 'NY Times' and labelled in extremis as “a squalid shoot 'em up for morons” by Joe Morgenstern in 'Newsweek'. Pauline Kael launched a 9000 word defence, a counterattack on the critical consensus. She reportedly persuaded Morgenstern, for one, to re-view the film; he recanted, which was unprecedented. 'Time' magazine came out with a cover story on the New Cinema - “Violence … Sex … Art” - prominently featuring Bonnie and Clyde. Robert Towne said that “without her, B & C would have died the death of an effing dog”; for the writers, Benton and Newman, her review was the best thing that ever happened...it put us on the map” (Biskind 40).

|

| Pauline Kael |

Kael was motivated, in the defence of the film, to range combatively over issues like film's status as mass art, the Barrow gang as outlaws holding a special place in the public imagination and as film art, comparing it with the classic You Only Live Once (1937). Another retelling of the B&C story, They Live by Night (1948), was a notable debut by Nicholas Ray as director, “a very serious and socially significant melodrama” which made little impact on American audiences - “its attitudes,” writes Kael, “were already dated thirties attitudes” (61). In Fritz Lang's film, contemporary audiences were also shown the “outlaw couple” as tragic figures, unremittingly portrayed as victims of fate. For young audiences in the late sixties, the period setting of the Depression was already distanced into a seemingly simpler time in which the outlaws are 'innocent' identification figures transformed into “Depression people” but killers nonetheless; the Depression is not being used to heighten social consciousness. “Audiences are not given a simple, secure point for identification” (Kael 64).

Beatty's portrayal of Clyde Barrow's dysfunctional masculinity - an expression of vulnerability and understated torment that is extraordinarily touching - breaking new ground in the portrayal of the gangster anti-hero. Penn's sensitivity to the ironic contradictions in the couple's spontaneously murderous bloodletting, and the denial of it, expressed in Bonnie's published poem, of themselves as “honest, upright and clean,” is central to Penn's embrace of a revitalised romanticism in Bonnie and Clyde (see below) already apparent in The Left-Handed Gun. This contrasts with 'B' movie surrealism, for example, of the amoral portrayal of l'amour fou in the earlier evocation of the outlaw couple on-the-run drawn together by a mutual love of guns in Gun Crazy (1949).

|

| Clyde's death, Warren Beatty, Bonnie and Clyde |

To quote Robin Wood, “even in death [Bonnie and Clyde] are completely alive, and it is the insistence of life within them – of spontaneous, socially amoral and subversive energies – that makes it necessary for them to be destroyed,” for what Wood calls “the artist's tragic sense” (75). Kael concludes that, in its comic tragedy, “Bonnie and Clyde, by making us care about the robber lovers, has put the sting back into death,” (79) standing in stark contrast with the obligatory sentimentalising of the lovers' deaths overlaid on the ending of Lang's film, presumably with his resigned acceptance.

Old Hollywood’s last stand

The initial industry indifference and mainstream critical assaults on Bonnie and Clyde's first release can be seen, in retrospect, as a last stand by 'old Hollywood'. The film's spectacular comeback after the initial debacle, contributed to the prospect of the opening of further unbridgeable gaps between the tropes of classical narrative and those of a 'new' romanticism. Kael, in her essay, takes issue with other pillars of the classical system then in retreat: censorship and the violence which raised many voices against Bonnie and Clyde which, she argues, “is essential to the film's meaning... art is not examples for imitation- that is not what art does for us.” Kael also further insists that the deployment of violence in non-art films should also be beyond the ambit of law singularly dedicated to the preservation of “giant all-purpose commercials for the American way of life.”

Kael finds cause to praise the editing of Bonnie and Clyde “as the best in an American movie for a long time,” for which she “assumes” Penn deserves credit along with the credited editor, Dede Allen. She finds it “particularly inventive in the robberies” and “brilliant,” in what she calls, “the rag doll dance of death” at the end (which Biskind confirms was originally Penn's concept), particularly noting the quick panic of Bonnie and Clyde looking at each other's face for the last time, as the gun blasts keep [their] bodies in motion, is brilliant...a horror that seems to go on for eternity yet it doesn't last a second beyond what it should.”

|

| Arlo Guthrie, Alice's Restaurant |

Kael goes further in identifying Penn's “gift for violence, and, despite all the violence in movies, the gift for it is rare,” a gift she intriguingly considers Penn shares with Eisenstein, Dovzenko and Buñuel (75-6). Penn and Allen edited four more films together: Alice's Restaurant (69), Little Big Man (70), Night Moves (75) and The Missouri Breaks (76). Nowell-Smith comments that “Penn's films do not so much play with conventions as strain against them, extracting significance from the constant pressure of content upon form” (460 N-S ed.).

The fact that Penn was not credited as writer on any of his films is taken up by Kael to air her opportunistically recurring critique of auteurism: the claimed neglect of the writer. She makes the point that unlike European writer-directors like Fellini and Bergman, Penn was “far more dependent on his collaborators and the original material.” In canvassing the cause of the writer Kael does ignore the complexity of guild rules covering the allocation of credits in America. The opposite generally applies in Europe with the director invariably given a co-writing credit in France, for example, in recognition that he/she will have made, at the very least, significant contributions to the screenplay. In Hollywood directors of 'A' features in the studio system were usually allocated in the budget some weeks to work with the writer in pre-production. Penn acknowledged that he always worked closely with the writer in this way. An exception was the debacle of The Chase (see above). Even on his most personal film, Mickey One, Penn did not receive a co-writing credit.

To support her case Kael dismisses Penn's film as “an art film in the worst sense of the word” to support her case: “[Penn] had full control, proving that a director cannot redeem bad material.” At the same time Kael acknowledges that in Bonnie and Clyde “one cannot say to what degree it shows the work of the co-writers, Benton and Newman, and to what degree they merely enabled Penn to “express himself,” which illustrates the problem – screenplays have a very different role in the scheme of things than plays written for the stage. Here Kael imposes her own value judgement on the director's contribution to Bonnie and Clyde: “Penn is a little clumsy and far too fancy; he's too much interested in being cinematically creative and artistic to know when to trust the script” (74). Kael considers that “the solid intelligence of the writing and Penn's aura of sensitivity help Bonnie and Clyde triumph over many poorly directed scenes” (76).

The Romantic tradition

Boosting its claims as a seminal art film, Robin Wood in saying Bonnie and Clyde 'romanticises' the couple felt that, “perhaps the word can be restored to something of its original dignity by relating to the Romantic tradition – the movement that in English literature begins with Blake and has its last great explosion in D.H.Lawrence whose main source of vitality and impetus has consistently been the belief in the importance - even sacredness - of the spontaneous-intuitive side of man's (sic) nature.” (75-6). This claim would seem to best apply to this, Penn's most successful film with audiences by a wide margin.

|

| Gene Hackman, Night Moves |

In more contemporary terms I see romanticism grounded by irony in a dialectic that marks Penn's major films from The Left-handed Gun to Night Moves (The Miracle Worker and the self-admitted diversion of The Missouri Breaks are possible exceptions) reaching a point in Little Big Man and Night Moves in which “Penn's vision shows complete disintegration,” as Terence Butler contentiously puts it in a retrospective essay on his work entitled 'The Flight from Identity'. “For all the elemental force of its preoccupation with violence and pain” begins Butler, “Arthur Penn's cinema has been predominantly characterised by a mood of stasis, of energy dissipated rather than liberated, of characters existing disorientedly rather than [as] positively defined identities.” Butler finds that “while few American directors have explored the personalities of individual characters or rivalled the intricacy of character interaction in his later movies, Penn has always worked at a kind of dead end because of an obsession with stunted psychology; none of his characters has ever reached a state of self-knowledge” (43).

|

| Four Friends |

In the decade following the retrospective re-sighting, in Four Friends (1981), of the 50s and 60s through the experiences of a Yugoslav immigrant, it seemed that Penn may himself have felt the impasse he had allegedly reached and the intellectual and emotional energy used up - he had more than once in interviews referred to several years of personal crisis following the completion of Little Big Man. Otherwise he still also 'felt aroused' to make films, hence the episodic, multi-themed Four Friends which left ideologically committed Robin Wood somewhat puzzled, and Target (1985) which long-time Penn convert Geoff Andrew, in 'Time Out', found to be “far more ambitious and intelligent than most spy thrillers.”

************************************

Peter Biskind, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls Bloomsbury pb. 1999 Ch 1

Jean-Pierre Coursodon, “Arthur Penn” essay in American Directors Vol 2 McGraw-Hill pb.1983

Pauline Kael, “Bonnie and Clyde” October 1967 reprinted in Kiss Kiss Bang Bang Bantam pb ed.1969.

Richard Lippe & Robin Wood, “An Interview with Arthur Penn” cineAction 5 Spring 1986

Terence Butler “Arthur Penn: The Flight from Identity” Movie 26 Winter 1978/9

Robin Wood, Arthur Penn Movie Paperbacks Studio Vista 1967

Adam Bingham, Great Directors: Arthur Penn Senses of Cinema December 2002

******************************************

Previous entries in this series can be found at the following links

Notes on canons, methods, national cinemas and more

Part Two - Defining Art Cinema

Part Three - From Classicism to Modernism

Part Four - Authorship and Narrative

Part Six (1) - The Sixties, the United States and Orson Welles

Part Six (2) - Hitchcock, Romero and Art Horror

Part Six (3) - New York Film-makers - Elia Kazan & Shirley Clarke

Part Six (4) - New York Film-makers - Stanley Kubrick Creator of Forms

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.