Randomly searching and reporting on YouTube movies is a lot like running a Ciné Club. People I know watch the films and tell me what they think about them - except now I’m getting the responses from round the planet.

Damiano Damiani’s 1968 Il giorno della civetta/Day of the Owl is a suitable candidate for this process. Damiani followed the pattern of Luigi Zampa, Pietro Germi and Federico Fellini in moving from the internationally lauded style of the neo-realists into conventions recognisably the director’s own. Damiani’s 1962 L'isola di Arturo did get some international distribution and his 1963 La rimpatriata could have been mistaken for the work of Fellini (I Vitelloni) or of Francesco Rosi (I magliari).

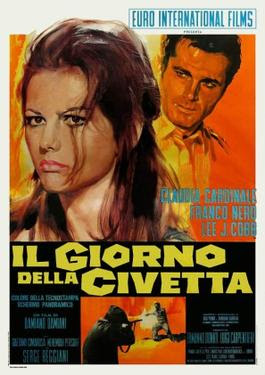

It was not until he moved into the westerns and thrillers that seeped into international drive-ins and grind houses that Damiani’s own voice became clear. Il giorno della civetta is significant in this process being the first of the crime movies which would dominate his output and his first pairing with Franco(Django)Nero then hot from his international outing in Camelot.

Il giorno della civetta kicks off with a truck driver taken out with a shot gun - a misleading opening. That’s all the action we get. Turns out that he was a local contractor who refused to pay protection. Investigating Carabinieri Captain Franco Nero finds Claudia Cardinale, the wife of a tenant farmer, whose home overlooks the crime scene, wandering the fields - looking for wild chicory and cabbages she explains. Her husband is nowhere to be seen. He often stays away nights you understand.

Nero and Cardinale, two of the eras so beautiful people, don’t really fit with the film’s realistic tone but Claudia (right) in particular goes easy on the glamour and one of the plot strains is that she’s too desirable to be left alone. Against expectation she doesn’t become romantically involved with Franco.

Turns out that local fixer Lee J. Cobb, backed by fellow Elia Kazan graduate Nehemiah Persoff, is running the rackets out of an office on the opposite side of the town square to the police station. Persoff points out that Nero is studying them through binoculars and there’s a figure eight mask sequence of square activity.

Informer Serge Reggiani (this film has a great cast) greets the priest as they pass in that square. It’s there that henchman Tano Cimarosa, (who later turns up in Cinema Paradiso), takes what, as Nero prompts him, may be the last good coffee he ever gets before being thrown into the caserna for murder. Cimarosa holds his own with the celebrity actors. Indignant Cardinale comes into the square’s barber’s shop to confront Cobb (“We always voted the way you wanted”) over her missing husband only to be told she’s in the way. At one stage Persoff plants a bomb in Nero’s car which would turn all this sleepy activity into a scene of murderous collateral damage and Cobb sends his lackeys in to spike a tire and remove the explosives under the pretext of changing it.

Nero’s Northerner Carabinieri officer resents the Sicilian abuses his force can’t prevent and starts fighting dirty, manufacturing a false confession - which Cimarosa eats. Nero’s brigadier alibis that unlike the Syndicate they feel remorse about their tactics. The word “vergonia” which figures so often in Italian films is heard again here. How often do people talk about “shame” in English language movies?

Lots of convincing detail like the two locals who have tried to disguise their hand writing by doing alternate words in the anonymous note while the syndicate sends information with letters cut out of newspapers. The press is shown as the instrument of the mob. Persoff’s aged mother drives past Claudia cursing her for having lured her now jailed son with her body, meaning hustling up a lawyer. The decades since the film was made are signalled by the scene of Cardinale’s young daughter bathing bare assed in a tub, an effective dramatisation of vulnerability which would be greeted with outrage now. Compare the teen whore scene in the De Iglasia 800 Balas.

This is all original and absorbing but the film doesn’t really work in its decision to avoid an action finale, instead making the climax Cobb’s monologue where he rates men (only) from a peak represented by himself and Nero through underlings to gays who are only half men. This fits into the film’s scheme as a counterpoint to Reggiani telling Nero that in Sicily there are lots of Police Marshalls and lots of evil doers but only a few informers, making Serge himself important.

This film is intriguing but it’s pivotal town square is less claustrophobic and chilling than the prison in the Damiani-Nero 1971 L'istruttoria è chiusa dimentichi/The Case Is Closed, Forget It or the police siege in the team’s 1978 Goodbye and Amen. I once heard Nero quote their 1971 Confessione di un commissario di polizia al procuratore della repubblica/Confessions of a Police Captain as an example of excellence these multi-lingual popular productions could achieve and he was right.

But it was all uphill for the makers. The festivals didn’t want to know, despite the intelligence and skill evident in these, unlike the more obviously Marxist Francesco Rosi/Gian Maria Volonte thrillers. In the English language market they only got spotty dubbed action in the drive-ins and grind houses.

Even in Italy, the cast including Nero and Cardinale were re-voiced by dubbing actors. Arturo Dominici has clear difficulty keeping pace with Persoff’s manic delivery. It couldn’t have helped that the film was sometimes called Mafia creating confusion with the 1972 Leopoldo Torre Nilsson Maffia and the 1962 Albert Sordi/Alberto Latuada Mafioso which sometimes traded under that title.

This whole area is grossly under-documented. Several of my correspondents who were enterprising enough to seek out La giorno della civetta call it the first Cosa Nostra movie, unaware of Germi’s exceptional 1949 In nome della legge from which it is to some extent formatted. Throw in the 1950 Black Hand, product of the Dore Schary era at MGM.

The Poliziottesco can be as thick witted and tedious as the more ham fisted Hollywood crime dramas but in the hands of talented film makers as here, it is a source of genuine satisfaction. I was delighted to find this one represented by a correct shape colour copy with good under the image English sub-titles. It’s been ignored for too long.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.