I’ve frequently been fascinated with the way that some stories take on a life of their own, surviving any number of variations, enriching or interpreting other works, and in turn being enriched by countless other works. And the story of Frankenstein is one of the supreme examples of this. A week ago, I picked up Mary Shelley’s book Frankenstein or the Modern Prometheus. First published in 1818, within five years a version had been staged in London.

I’ve frequently been fascinated with the way that some stories take on a life of their own, surviving any number of variations, enriching or interpreting other works, and in turn being enriched by countless other works. And the story of Frankenstein is one of the supreme examples of this. A week ago, I picked up Mary Shelley’s book Frankenstein or the Modern Prometheus. First published in 1818, within five years a version had been staged in London.

She was writing at a time when science was playing more of a part in a world previously dominated almost exclusively by religion. She does raise questions such as the morality of science and medicine. Ideas of ethics and responsibility are very much part of the narrative though never in an overt polemical way. These questions remain relevant two hundred years later, the myriad versions amply proving that. But she also told a ripping monster yarn.

Which led me to thinking about all the manifestations her creation has had. So, my viewing in the last lock-down week has been Frankenstein, the first known film version made in 1910, ten features and shorts, a National Theatre production, a TV series, even a Mr. Magoo cartoon. But so fertile has been the off-spring of Mary Shelley’s creation that this is a mere fraction of all the various versions, continuations, satires, references, and so on over the years. (See my list at the end of this article.)

The structure of Shelley’s book fits literary conventions of the time. Supposedly a series of letters or journals, there are three narrators. The first letter writer is a ship’s captain, writing from St. Petersburg to his sister in England, her telling about a strange meeting he had in Arctic waters with one Victor Frankenstein. Frankenstein has been chasing a creature that he says he created. His account is the books’ second narration. And the third narrator is the Monster itself, articulate and literate.

In looking at the various versions, I became aware of several key points. First is just how the monster is created. Then there is the nature of the monster, and then the fate of several key characters by the end of the story.

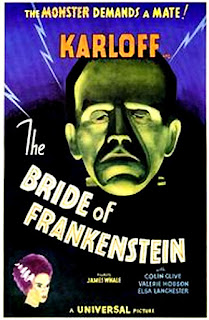

To hold the audiences, he inserted the detailed creation scene – body parts gathered, and stitched together, elaborate laboratory equipment, lots of arcing electricity, and bubbling test tubes. The make-up for Boris Karloff was part of this, visually spectacular, but all justifiable in the narrative being developed. Stitches showing the different body parts, bolts in the neck to be conductors for the electricity needed to bring him to life. Whale’s vision quickly became the image for the Monster, imitated in countless subsequent films.

Also, so many films now have their own interpretation of Whale’s account of the creation, not Mary Shelley’s. Of course, it is reprised in Whale’s follow-up Bride of Frankenstein, which incidentally is closer to parts of Mary Shelley’s story than I imagined. Frankenstein is importuned make a mate, in the book by the Monster, in the film by a sinister Dr. Pretorius.

Whale made another significant contribution to the monster’s image. A tall, lumbering, grunting, inarticulate monster, there is not much intelligence or sensibility here. Yet, Mary Shelley’s monster could read, and speak. He could quote Milton’s Paradise Lost– and understand it. He apprehends the morality of what he is doing, and what has been done to him. His killings are not random or acts that he doesn’t understand. This is a significant re-characterisation. Mary Shelley’s monster is not a random killer. His murders come from his deep sense of loneliness, difference and estrangement. He does have an experience of being accepted as ‘normal’ by the blind man from whose household he learns to read and philosophise. He knows what he is missing by never having been loved, even by his creator. He demands a mate from Frankenstein and the two killings of members of Frankenstein’s family stem directly from his being thwarted in this request. With this perspective, his killings are understandable, and evoke a painful understanding from us. But these murders are never justified or excused by Mary Shelley.

Whale made another significant contribution to the monster’s image. A tall, lumbering, grunting, inarticulate monster, there is not much intelligence or sensibility here. Yet, Mary Shelley’s monster could read, and speak. He could quote Milton’s Paradise Lost– and understand it. He apprehends the morality of what he is doing, and what has been done to him. His killings are not random or acts that he doesn’t understand. This is a significant re-characterisation. Mary Shelley’s monster is not a random killer. His murders come from his deep sense of loneliness, difference and estrangement. He does have an experience of being accepted as ‘normal’ by the blind man from whose household he learns to read and philosophise. He knows what he is missing by never having been loved, even by his creator. He demands a mate from Frankenstein and the two killings of members of Frankenstein’s family stem directly from his being thwarted in this request. With this perspective, his killings are understandable, and evoke a painful understanding from us. But these murders are never justified or excused by Mary Shelley.

With Whales’ approach the killings are still horrific. Now they have the sense of being random – and we fear we could be a victim. Or anyone in the story could be a victim. So we have a different sense of the horror. Later versions (for example Morrisey’s Flesh for Frankenstein) add a new dimension, where the monster is controlled by Frankenstein to carry out specific murders - perhaps like Caligari’s Somnambulist.

But filmmakers often think that audiences need a happy ending. So, many versions (starting with James Whale’s) see Frankenstein and Elizabeth survive and live happily ever after (or until the next sequel). Whale’s changes to the monster’s character are consistent with how such an ending can be provided.

The monster has appeared in many other films, based on the idea that he survived. These have been some of the more interesting films as they explore more potentials for the creature.

So many variations, adaptations, re-interpretations. Many are very entertaining or satisfying films in their own right. But all prove one thing – after two hundred years, Frankenstein’s creation still lives!

…..

These are the films I watched, with brief comments and indication of sources. Clearly there are many more I did not watch, including the large number of ‘Frankenstein meets ….’ films. Check justwatch.com for other sources some films may have.

A beautiful restoration of the full 12-minute film. It really packs in the spirit of the book surprisingly well, with some very effective cross-cutting, a bit surprising for its date.

Frankenstein (James Whale) 1931 Available on DVD

Still a terrific film. Significant differences from the source novel, but the impact of the film justifies them. Many of these changes have themselves become part of the Frankenstein legend and ethos.

Bride of Frankenstein (James Whale) 1935 Available on DVD

Whale again makes a great film. Surprising little prelude explaining how the story came into being, with Elsa Lanchester as Mary Shelley. Then, Lanchester re-appears as the Monster Bride. Is Whale making a comment about Shelley’s inspiration?

The Famous Adventure of Mr. Magoo – Doctor Frankenstein (Abe Levitow) 1965 Watch it on YouTube

Standard Mr. Magoo when he moved from his Cinema slots to a cheaper on-going children’s TV show in the 60s.

Frankenstein The True Story (Jack Smight) 1973 Watch it on YouTube

A two-part story made for English TV, with an overladen Quality Prestige cast (James Mason, Jane Seymour, Margaret Leighton, etc) Michael Sarrazin is the monster, so beautiful at creation, but like Dorian Gray his appearance regresses as his true nature comes out. Passable.

Flesh for Frankenstein (Paul Morrisey) 1973 Available on DVD

Produced by Andy Warhol, and originally shown in 3D, so you could flinch at body parts thrust at you. Kind of fun in a shlocky way, this is a continuation where Frankenstein uses his monster in his vendetta against the Serbs. Morrisey seeks any excuse for having beautiful virgins naked. And because Joe Dallesandro is in it, he’s there full-frontal too.

A Japanese cartoon version made for Toei, in an English-dubbed version. Absolutely basic animation, though some reasonably attractive backgrounds. Curious.

Frankenstein Unbound (Roger Corman) 1990 Watch it on Youtube

A discovery. Here’s a story with imagination. It starts in 2030, but through a time slip our hero John Buchanan (a very young looking John Hurt) finds himself (and his 1990 idea of a driverless car for 2030) finds himself in the Swiss village where Mary Shelley (Bridget Fonda) is living with Shelley (Michael Hutchence – yes) and struggling to write her novel. Buchanan tells her it will be a great success. Raul Julia is Frankenstein. Lots of fun. I’m sure the source novel by Brian Aldiss is significant here. And Corman really knows how to sling a film together.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (Kenneth Branagh) 1994 Available on DVD

A prestige production, boasting complete fidelity to the novel. This is probably about 80% correct. Branagh directs and stars as Frankenstein. He’s probably not charismatic enough without Shakespeare to animate the film, but Robert de Niro is a compelling monster.

Frankenstein (Danny Boyle, National Theatre Stage Production) 2011

Very much a stage production. A prestige theatrical event for people who wouldn’t go to see a Frankenstein film. The theatrics are over-produced, though probably effective in a theatre. It’s gimmick was being performed alternately with its stars Benedick Cumberbatch and Jonny Lee Miller as Frankensein and the monster.

I, Frankenstein (Stuart Beattie) 2014 Screening on Netflix

A multi-plex CGI video-game type story, where the monster has survived for over 200 years. Gargoyles and Demons are engaged in a war for dominance over mankind. If they can get Frankenstein’s notebooks now in the possession of the Monster, the Demons can animate hundreds of bodies they have stockpiled. I was surprised to see that this was actually made in Melbourne. Good production values, but no interest in characterisation, or real creative ideas.

The Frankenstein Chronicles 2 X 6 episodes (Benjamin Ross, Barry Longford ) 2015-2017 Screening on Netflix

Taking the story further can be rewarding. This is London 1828, about ten years after the publication of Mary Shelley’s book. Some gruesome murders of children from the slums and river side areas could be inspired by Dr Frankenstein. Attention to historical events and people is great. Shelley, William Blake are involved at one point. Trying to report for his newspaper is a young journalist Charles Dickens, calling himself Boz. As he was at that date. And events are taking place against the introduction into Parliament of the Anatomy Act, which was first tabled in 1828, a bill aimed at eradicating the use of bodies from graves, and so on in anatomy dissections and research. I’m not quite finished the second series at time of writing. Very much enjoying, though just a feeling with a couple of episodes to go, it may be circling to jump a shark.

Mary Shelley (Haifaa Al-Mansour) 2017 Screening on Beamafilm

A bio-pic of Mary Shelley. A very interesting life story to tell. But it doesn’t rise about the prestige British film. And Elle Fanning just doesn’t work in the title role.

Frankenstein’s Monster’s Monster Frankenstein (Daniel Gray Longino) 2019 Screening on Netflix

A 30-minute self-indulgent piece, with the main curiosity being, how did this get to Netflix? Using the tedious mockumentary format a filmmaker is trying to investigate the career of his father who had played Frankenstein in a television play some time back.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.