I once took a painting into Sotheby’s in London to have it authenticated. Despite the signature, it seemed too much to hope it really was by Raoul Dufy. The head of Modern Painting, Julian Barran, confirmed my doubts.

“It’s quite good, though,” he said. “Might almost be an Elmyr.”

Well, having a painting by ace forger Elmyr de Hory, featured in Orson Welles’ F for Fake, was almost as good as having the real thing. Almost.

Barran pointed out that the signature used a colour of paint not present in the picture itself. Someone added it later. And De Hory was known never to sign his work, leaving that to the unscrupulous dealers who bought it.

“Yes, Elmyr was a rogue,” Barran concluded, “but not a villain.”

The distinction came to mind this week when two seasons on French TV, one devoted to Vincente Minnelli, the other to Georges Franju, intersected in one of those dream double bills - Minnelli’s 1948 The Pirate and Franju’s 1964 Judex.

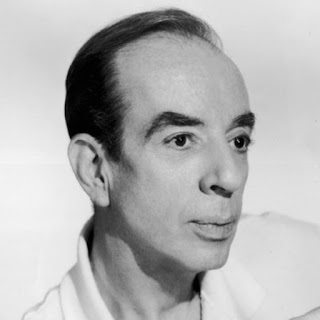

|

| Vincente Minnelli |

The Pirate came complete with a back-story of disaster; performers like Lena Horne excluded on racial grounds (though Kelly smuggled in the Nicholas Brothers): Garland behaving even worse than usual, requiring the daily presence on the set of a psychiatrist: Louis B. Mayer, who thought the story “too highbrow”, demanding Kelly tone down the violence in the Mack the Blackballet (Remove references to killing babies? How bourgeois.) and excise entirely the number Voodoo as too erotic.

Happily, there’s lots left, including Niña,one of Kelly’s most inventive appearances ever, with an extraordinary exhibition of acrobatics in and around the balconies and walkways of a set obviously calibrated to the centimetre to fit his choreography. That over, the music

shifts, after a lyric opening, into a rhumba during which Kelly prances around a bandstand supported on vertical poles. His jerky, almost grotesque movements, with bent elbows and knees, grimaces and hand gestures, and including some flamenco stamping, all with a brassy Conrad Salinger orchestration, are as unlike other Kelly numbers as the song itself. How much the studio disliked everything about it can be inferred from Kelly’s sound-track recording. It speeds up the tempo, and its Cuban beat, not to mention the orchestration, is submerged in a sludge of conflicting tempi.

As for Judex, in Australia it came out just after we were bewitched by Jules et Jim and Vivre Sa Vie. The general reaction in informed circles, not only in Australia, was “What’s this shit?” You really needed to know the pre-World War I serials of Louis Feuillade of which it was a pastiche. That excluded almost everyone, myself included, Then, too, it was filmed in a misty monochrone, nothing like the crisp blacks and whites of Raoul Coutard and Henri Decae. Who knew that Franju, au fond a cinema historian – he co-founded the Cinématheque Française with Henri Langlois – was evoking the orthochromatic film on which those early films were shot?

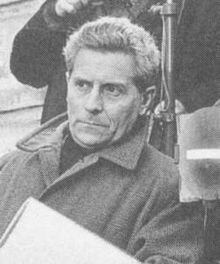

|

| Georges Franju |

Judex is built around an outlaw as well, the avenger Judex, who leads his troupe of masked, caped and gloved helpers around pre-World War I France in a vendetta against Favreau, a crooked banker, in the course of which they must also foil the efforts of a criminal gang to kidnap the banker’s daughter.

Jack Nicholson advised Michael Keaton, nervous about playing Batman, “Let the costume do the work.” Franju cleaves to the same counsel. Judex, in the person of stage magician Channing Pollock, arrives in tails at a costume ball in Favreau’s chateau where everyone has the mask of a bird. His is that of a falcon (below), Favreau’s, naturally, a vulture. After wowing the crowd by producing dove after white dove from his person, he pauses only to hand Favreau a flute of drugged Dom Perignon and disappears into the night. Joaquin Phoenix isn’t in the race.

As in Batman, where the true star, judged by flamboyance and prominence in the story, is The Joker, the most effective menace in Judexisn’t embezzler Favreau or even Judex but the leader of the kidnap gang, Diana Monti, the role that, for Feuillade. was played by Jeanne Roques, alias Musidora.

One can only guess at the effect of Musidora’s black body stocking and domino mask on adolescents of a century ago, but as Monti in Judex, Francine Bergé is no slouch. She is so much more fun than Edith Scob as the frail heiress, forever fainting and having to be rescued - on one occasion from a river on which she serenely floats, Ophelia-like, watched incredulously by some kids fishing.

|

| Francine Berge, Judex |

YouTube has some clips from The Pirate, including a portion of Niña, though with a witless preamble about Kelly “inventing pole dancing.” Kelly’s soundtrack performance can also be heard, in all its horror, as well as the audio of Voodoo. Judex is better served by the full version, without, however, English titles. Not to mention the Feuillade originals.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.