Editor's Note: This is the second memoir by John Baxter recalling his early days in Europe as a cinephile on the loose. The first, recalling his introduction to life on the Venice Lido during the film festival, can be found if you click here

|

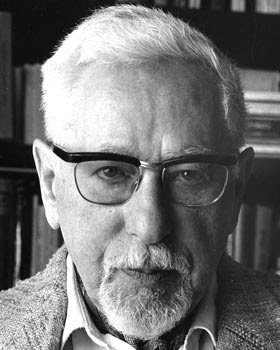

| Lotte Eisner |

One meeting at Venice in 1971 stands out.The festival presented a retrospective of German fantasy films, curated by the doyenne of Teutonic cinema studies, Lotte Eisner. Tiny, talkative, driven, and delighted that I knew her book about Expressionist film, The Haunted Screen, Lotte took Monica and I under her wing.

She was, she explained, writing a biography of Fritz Lang (cover left). Leafing through a little book I’d written, Science Fiction in the Cinema, she was transfixed by a photograph oftechnicians standing amidst the model skyscrapers of Lang’s future city, Metropolis ,manipulating the tiny cars on its swooping roadways.

“But…I have never seen this picture before!”

That was no surprise. It came from a collection unique to Australia. It had been taken in Berlin during the 1920s by an amateur named J.C. Taussig, who later emigrated, and gave his collection to the National Library in Canberra.

“But I must have these for my book!”

When I offered her my own prints, she threw her arms around me.

“If there is ever anything I can do for you….”

“Well, as a matter of fact….”

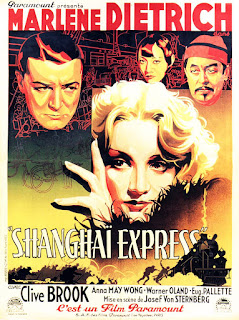

I told her of my hope, conceived after meeting Josef von Sternberg (right) in Sydney, to write something about his work.

Which is how I found myself in Paris a few months later, facing the Palais de Chaillot, that art deco complex on the heights of Trocadero, constructed for the 1937 World’s Fair.

Viewed across the Seine, from under the Eiffel Tower, there’s a majestic sweep to the Palais. It reminds some people of Albert Speer – Hitler too, apparently, since he chose it as the site to be photographed surveying the city he’d just conquered.

Lotte had simply given me the phone number of Mary Meerson, assistant to Henri Langlois, head of the Cinematheque Francaise, and told me a screening of von Sternberg films was “all arranged.”

Friends in London hooted with laughter when I told them this. Though none had actually met Langlois, each had a horror story – about the African diplomat, for instance, who, bearing the highest credentials, requested a tour. Langlois greeted him at the door, waved him ahead, then slipped down a side passage, leaving him to wander until he got fed up and went home.

On the phone, Madame Meerson (left) was cordial, if curt. “Be here at 10 on Monday morning,”

The guard at the door was courteous, but my meagre French was unequal to his directions, since I soon found myself not in the offices of the Cinématheque but its museum that filled the whole wing of the building above the screening theatre.

It was still an hour before opening time and the place was empty – all the more reason to take a peek. Once in, however, I had no wish to escape. Each turn in its crooked, narrow aisles drew me on to some new wonder; James Dean’s leather jacket from Rebel Without a Cause, a fragment of the jagged Expressionist décor of The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari, even the shell of the robot from Metropolis. Looking at that tight-lipped malevolent image of Woman as Destroyer, I believed for the first time those rumours that Lang had murdered his first wife.

|

| Henri Langlois at the entrance of the Cinematheque francaise in the Palais de Chaillot |

I half expected to stumble over the desiccated dashiki-clad corpse of the African abandoned by Langlois. Instead, a heavy metal back door opened onto a staircase. At its foot was the park behind the Palais that sloped down to the Seine. Directly under my feet, I recognised the shallow ramp, more like a garage forecourt than a theatre, that led to the Cinématheque’s cinema.

In newsreels, I’d seen Jean-Pierre Léaud, star of Francois Truffaut’s autobiographical Antoine Doinel films, stand on that abutment in May 1968, haranguing the cinéphilesas masked and helmeted troops lined up with their round shields and billy clubs, ready to charge. Truffaut used the entrance as the opening image of La Nuit Americaine, his celebration of film-making, and in The Dreamers Bernardo Bertolucci chained Eva Green to its glass doors.

Those doors were locked, but as I peered inside a man materialised from the gloom.

“C’est Monsieur Baxter?”

“Um, yes…I mean, oui.”

He unlocked the door and beckoned me inside.

We stepped into the neat little cinema. All modern film scholarship started here, with a few dozen young men and women watching films which existed solely because Henri Langlois had preserved them from the Nazis and the stupidity of his own bureaucracy.

“Alors, ou voulez vous commencer?”

Where did I want to start? As I looked blank, he nodded towards the projection booth. Unlike regular cinemas, it didn’t have a single glazed port in a solid wall,

just a sheet of glass as big as a department store window. Piled beside the 35 mm projectors were dozens of shiny new metal cans. I read the labels in awe. The Blue Angel, The Salvation Hunters, The Scarlet Empress, Shanghai Express….every film, it seemed, that Josef von Sternberg ever directed.

“But…so many.” I pointed to my watch. “How long?”

He shrugged. “Jusqu'à seize heures l'après-midi - et chaque jour cette semaine.’ Until 4 p.m. that day, and every day that week, the theatre was reserved for my exclusive use. All this – from one chance encounter, and a single phone call.

With a sense of joining a phantom congregation of a million co-religionists, I draped my coat over the seat and took my place in the front row.

“The Docks of New York, s’il vous plait, m’sieur.”

I was home. And I’ve never really left.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.