In 2018, my usual travels to film festivals in Hong Kong, Sydney, Bologna and Tokyo were extended to two months in Northern Europe from three cities in Poland to Denmark, Sweden and Norway. Without withdrawals developing in a physiological way, I saw only one film through this journey and that was right at the beginning in Kracow where a boutique series of cinemas included Kirill Serebrennikov's LETO (SUMMER) showing with English subtitles. Peter Hourigan has described the film with enthusiasm here recently during its Australian appearance in a Russian Film Festival. Meanwhile, between visits to ancient castles, long and spectacular railway journeys and very many magnificent gallery explorations, I was impressed by the enthusiasm for film exhibition in specialised centres in several cities. Unfortunately, some similar institutions were not able to be included in Poland and Sweden.

1. Imaginative film screenings in Scandinavia.

Tromsø is a city of about 70,000 people in the very northern part of Norway, way past the Arctic Circle. The main part of town and the cultural hub is on an island connected by bridge to the mainland at the point where the beautiful 1965 Arctic Cathedral is a popular attraction by day and for midnight concerts at night. Although some parts of the year offer 24 hour darkness in winter or total sunlight in the summer, clinical depression in Tromsø seems less a community problem than in other parts of the world with such extreme variations of illumination.

One would like to think that contributing factors might be a lovely mustard-coloured intimate cinema, the 1915 Kinematograf (left, click on the image for enlargement and a slideshow) and a most impressive glass-walled library with adjoining multiplex cinemas constructed under the curved roof of a former downtown theatre of fifty years ago. In addition there are opera and ballet performances in a cultural complex as well as music of other genres, some performances of which are in the century-old cinema, said to be the northernmost continuously operating movie-house in the world. Programmed under the banner of Verdensteatret Cinematic (see program guide below), the programming range is diverse from contemporary arthouse to important films of the past for example by Resnais, Bergman, De Palma, or John Ford.

The single cinema auditorium seats just over 200 with murals added by local artist Sverre Mack a few years after the opening. In addition to regular film screenings, the theatre provides a community hub, especially on those long and longer winter's nights, with a coffee shop and bar, music provided coming from records on the wall of LPs. Film festivals play from time to time including an international one shared with the multiplex nearby.

In Oslo, the Norwegian Film Institute building, Filmens Hus, includes two cinemas and the only film museum in Norway along with its important national collection of film-related items. Contemporary arthouse films are interspersed with important films of the past arranged in seasons. The thick quarterly Cinemateket programme guide (left) runs to over sixty pages. Sometimes films are imported for exclusive screenings in these venues. Recently Last Flag Flying, An Elephant Sitting Still, and Burning were intermingled with seasons devoted to major silent films, Agnes Varda, Marlene Dumas and Edvard Munch in associated with the Munch Museum, Romanian cinema and cycles of older Norwegian classics.

The Danish Film Institute in Copenhagen is in a beautiful location opposite the King's Garden and Rosenborg Castle. There's an excellent film programme at the Cinemateket (right) along with a book and DVD shop, cafe, library and Videotheque in a building that houses offices for the institute's administration. Their significant bi-monthly programme recently included music films, Syrian documentaries, new Danish films with English subtitles, Ingmar Bergman reaches 100, films of Brian De Palma, Golden Days of B-films from the 40s to 70s, films from Chile and a tribute to the Marx Brothers.

A day's film programme might include works by Martel, Pasolini, Malmos and Spike Lee or titles like The Rider, Django Unchained and Time Regained. During my visit to the city an annual international film festival was about to begin and promised a screening of the much-anticipated Bi Gan's Long Day's Journey into Night but again it was just out of reach, happening two days after my departure. Finally, I caught up with this film of the year at Tokyo FILMeX.

2. Japan

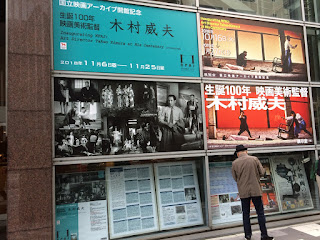

The National Film Archive of Japan (2018, exterior left) is a new cultural institution. It was created following the separation of the National Film Center from the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo and occupies the building of the former Film Center. Over several levels the Archive has two cinemas and both permanent and temporary exhibitions related to Japanese cinema. A more permanent display moves through the history of the national cinema displaying equipment, film clips, posters and written documents. These are annotated helpfully in Japanese, Chinese, Korean and English. During my November visit, there was a temporary exhibition devoted to the work of art director Kimura Takeo at his centenary. His last credit was at the age of 90. Kimura (1918-2010) was most renowned as an art director, particularly with some Suzuki Seijun films at Nikkatsu such as Tokyo Drifter. He was also a writer and filmmaker.

3. The Stormy Night

Earlier in the year, during the Hong Kong International Film Festival, an unrelated miracle occurred. A campus screening of The Stormy Night, (right) a Chinese silent film introduced by Professor Shi Chuan from Shanghai Theatre Academy, an event hosted by Hong Kong Film Critics Society.

The Stormy Night is a 1925 Chinese silent film written and directed by Zhu Shouju in Shanghai. Zhu was a writer, editor of Movie Magazine, film producer and director of over a dozen films. Of the films he directed himself, only this almost complete copy of The Stormy Night has been found. Among the missing films are several featuring the legendary actress Ruan Lingyu, tragic star in real life and subject of Stanley Kwan's Centre Stage in1991.

The Stormy Night itself was among the missing as well until a magnificent discovery in 2006 when descendants of film maker Kinugasa Teinosuke (A Page of Madness, Gate of Hell) donated his personal collection to the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. Sometime later, staff discovered reels of a film with Chinese intertitles but as the opening credits were missing, it was assumed one 35mm reel had been lost and it took some time to ascertain that the remaining reels were the precious only surviving footage of Zhu's directorial work. Shelley Kraicer has written, and other authorities on Chinese cinema of this period have told me, that they find the film a revelation and something by which the history of late Chinese silent cinema must be re-assessed.

The surviving eight 35mm reels commence during a scene in which a middle-class husband is told by his doctor that he must take a break from his busy life in Shanghai. He's recommended to rest and seek recreation in a quiet small town. We were told that the scenes in the provincial town were shot in the director's own home town. The trip develops into a journey of moral distractions and spiritual discoveries unfolding in the style of a Lubitsch comedy.

It seems no coincidence that Lubitsch's The Marriage Circle was released in early 1924 and The Stormy Night at the end of 1925. The film is also an important example of the "Mandarin Duck and Butterfly" school of Chinese literature in the early 20th Century. We were told that the video copy screened was from that print found in Japan on 16mm. Just the same the exquisitely detailed and illuminated images suggested a close approximation of 35mm.

4. John Turner's Epic History

Finally, a publication that is a work of much research, long gestation, enormous rigor and more fortitude than I can imagine. John Turner's The History of Australian Film Societies and their Contribution to Australian Social and Cultural Life was published this year by the Australian Council of Film Societies, an organization to which the author has devoted much of his life and enthusiasm. In over

The final chapters cover various causes such as importation costs on prints, censorship, submissions to government inquiries, DVD rights for film society screenings and a look at today's scene and its future prospects. There are various appendices and a good index which must have been a work in itself.

Work on the book has taken the best part of two decades after the author, on retirement, decided to "interview all the living legends who had been involved with film societies since the early days." It's a significant addition to the history of film culture in Australia and mandatory reading for anyone researching not only the genesis of non-commercial film exhibition but also the fascinating trail of where some prominent organisations today found their roots and inspiration.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.