|

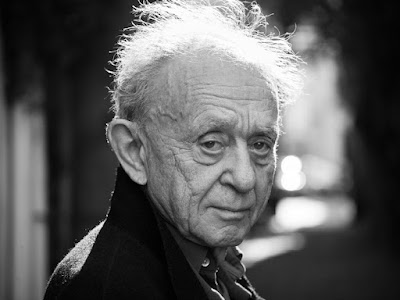

| Frederick Wiseman |

Editor's Note: But first....This is the introduction to the Frederick Wiseman retrospective in the SFF catalogue:

IT TAKES TIME: TEN FILMS BY FREDERICK WISEMAN

“I’m making movies about common human experiences, which differ from place to place because traditions, customs and habits differ. But the basic experiences are the same. I think my subject is ordinary experience. I attempt to create a dramatic structure drawn from ordinary experience and un-staged, everyday events.” – Frederick Wiseman

In an award-studded career spanning seven decades, acclaimed veteran filmmaker Frederick Wiseman has invited us into worlds we may never have known we cared about until he showed them to us.

His ‘reality fictions’ – he disdains notions of cinéma verité, direct or observational cinema – chronicle the functioning of contemporary American institutions (schools and prisons, libraries and welfare agencies), with occasional explorations of illustrious international establishments of every ilk and what makes communities tick.

His patient gaze, which eschews narration, interviews and background music, reveals the lives and experience of people within these structures or neighbourhoods, be they on the job or enjoying iconic sites such as Central Park. At times it also captures the creative process.

Though his apparently neutral camera seems to dispassionately record whatever it happens upon, often from up close, Wiseman’s highly structured oeuvre – editing the many hours of footage can be a year-long process – conveys empathy with its subjects. It is also clear that he engenders trust, his camera is never intrusive.

After an early venture into film production, Wiseman decided to make films he would direct, produce and edit himself. “The most sophisticated intelligence in documentary”, to quote Pauline Kael, has followed this path ever since, creating a peerless body of work that, with passing time, offers a historical perspective of humanity in the 20th and 21st centuries.

It Takes Time: Ten Films by Frederick Wiseman at SFF Book at sff.org.au/wiseman-retrospective

**************************

|

| Domestic Violence |

CRITIC AND SCHOLAR TOM RYAN WRITES: “Voyages of Discovery”

For a variety of reasons, despite the fact that Frederick Wiseman is widely regarded by many as the world's greatest living documentary filmmaker, his work hasn’t been widely distributed Down Under. One of these reasons is the running-times of his films, which frequently make considerable demands of their viewers.

While this might be a turn-off for some, there are inestimable rewards on offer in the ways in which Wiseman allows us to discover the daily rhythms of the institutions he visits, whether it be the Atlanta University Primate Research Center, in Primate (1974, 105 minutes), the terminal ward of Boston’s Beth Israel Hospital in Near Death (1989, 358 minutes), the Central Park East Secondary School in New York's Spanish Harlem, in High School II (1994, 220 minutes), or Chicago’s Ida B. Wells housing development project in Public Housing (1997, 195 minutes). Or, indeed, in Domestic Violence (2001, 194 minutes), which depicts the cycles of interviews, therapy sessions and staff meetings around which Florida’s The Spring operates.

Occasionally, film festivals have sat up and paid attention. But local audiences have otherwise been denied the chance to see his work. Now, that’s about to change. A welcome partnership between ACMI in Melbourne, the Sydney Film Festival and the National Film and Sound Archive in Canberra is offering a 10-film retrospective of the still-active 92-year-old’s work along with a pre-recorded master-class.

From his 44 feature-length documentaries, two fiction films and the handful of other projects for TV, there’ll be chances to see both his first film, Titicut Follies (1967), and his most recent one, City Hall (2020), as well as Welfare (1975), Central Park (1989), High School II, Belfast, Maine (both1999), Domestic Violence, La Danse: The Paris Opera Ballet (both 2009), In Jackson Heights (2015), and Ex Libris: The New York Public Library (2017).

Wiseman’s approach is simple, direct and highly disciplined. He doesn’t use interviews, narration or superimposed captions, and you’ll never see him on camera, asking questions (like Errol Morris) or being an agent provocateur (like Nick Broomfield or Michael Moore), or arguing a case (like your usual TV doco). He’s always talked modestly about his films as “voyages of discovery” and his style is observational, the camera serving as a patient, unobtrusive witness, sitting back and watching rather than darting about frantically, wearing its vérité spontaneity on its sleeve.

He meticulously follows his own rules and his view of the events he’s recorded only emerges through the editing, in what he chooses to show us and how he orders it. He assembles his material as an artist rather than an instructor, respecting the intelligence of his audience, allowing understandings to emerge rather than dictating what they should be. As he puts it in the same measured tones that are evident in his films, all of them should speak for themselves.

The following interview was recorded prior to a screening of Domestic Violence at the Melbourne International Film Festival. It is being published here (in two parts) for the first time.

*****

I understand you’re currently editing Domestic Violence 2?

I’ve just finished editing it.

What made you feel another chapter was necessary?

Well, the first film, as you know, deals with the police and the shelter. The second deals with domestic violence in cases in three different courts, an arraignment court, an injunction court and a misdemeanour court. So, it’s another aspect to the issue, about the way the participants present the facts in the court and the way the court deals with them. Also in this movie you get to see the perpetrators, as they’re called. In the first one, you mainly saw the women and the children.

Did you have to shoot the same amount of footage for both?

The total footage for the two films was about 115 hours. They were shot consecutively. I went down to Tampa and spent eight weeks there. About four weeks of that was the first film and about four weeks of it was the second.

So do we actually see the same people in both?

No, you don’t see any of the same people because some of the cases of the women you see in the first movie had been disposed of in the court and some hadn’t reached the court. But you see similar kinds of cases. Nobody follows from one movie to the other.

It’s unusual for a filmmaker as reputable as you to have a sequel in their credits.

[Laughs] Well, it’s not a sequel in the traditional sense. It’s just another aspect of the same subject. It’s not like, er, ah, ah, er, what are they called, ah, Men in Black 2. (Further laughter]

I got the sense in Domestic Violence that the all-male police were well-meaning but ill-equipped to deal with the problems they found themselves faced with. Is this the way you experienced it from behind the camera?

Well, it depends what you mean by “ill-equipped”. Actually I thought they were pretty good. I don’t want to put myself in a position of making a judgment about police behaviour, because I’m no expert. But, in terms of the sensitivity they displayed in the situation, and given the limitations of what the law allows them to do, I thought they were quite good.

You say “all-male”, but there’s a woman cop in the last sequence in the film – although there are no women cops in the sequence at the beginning of the film. And in that last sequence, by law there was nothing they could do to arrest the man because he hadn’t yet committed a crime of domestic violence. And he was, in fact, the one who called the police. To me, that’s one of the reasons that it’s so interesting: because it’s so complicated. All they could do was try to reason with him. Even though he was drunk and even though he was threatening, he had in fact committed no crime. I don’t know what the situation is in Australia, but it’s true under Florida law.

I think it’s probably generally true.

To go to that final sequence: the camera wanders around the room, but there tends to be a recurrence of shots of the largely-silent female police officer. She was attentive, but she didn’t really speak.

Oh, she speaks a little bit, but not very much. The camera is also on the man when he speaks and on the cop when he speaks and on the woman who’s living in the apartment when she speaks. I haven’t figured it out exactly, but I would think that if the camera is on the woman cop for 10% of the sequence it would be a lot.

Maybe I was reading the film in terms of the male voices that dominated the police work and the female voices that dominated in the crisis centre and seeing that as suggesting things about the situation – as many of your films do – without declaring them specifically.

I think that’s probably likely. I mean “likely” in the sense that that was what the film was doing. I can’t speak for how you were reading it. Certainly I think – whether it works or not is not for me to say – but I think that in that last sequence there are all kinds of implications that are related to the events that you see in the earlier part of the film. The last sequence in many ways summarises principal aspects of what you’ve previously seen.

Was there an aftermath to that sequence?

I don’t know. I went off in the cop car and I know that I spent the rest of the night in that car and they weren’t called back to that particular neighbourhood.

You get the sense that the man is rationalising the situation: I called you, so you can’t blame me for what happens now?

Yeah. She’s gonna go sleep on the couch and he’s gonna go sleep in the bedroom and they’ll wake up in the morning or you don’t know if he’s gonna beat her up. You do know that he shot at her car two weeks prior to that, but it’s completely up in the air, so to speak.

There were also a lot of shots of women there – most of them African in appearance – who were sitting silently in the background…

A lot of the women didn’t talk in those group sessions. They were physically present, but they didn’t talk.

Did you ever try to draw them into the foreground?

No. I never try to provoke anyone to do anything, or stimulate anyone to do anything. My job is to record what’s going on as if I weren’t there. I like the audience to know that what they see and hear in the film would have taken place if I hadn’t been there. And I think it’s true that if I’d tried to bring them into the discussion, then events would take place or things would be said that might not have been said except for my presence.

But you could, for example, have used one of their interview sessions with a counsellor. Or was there something prohibiting that?

Frankly, I didn’t think of that as an issue. Many of the women in the interview sessions are not the women you see in the group. One or two of them are, but most of them aren’t. So I didn’t think about that particular question in relation to those women.

As a viewer, I became fascinated by them. I found myself watching them and their responses to the speakers to see if there was silent assent, but very often it’s almost as if they’re in another place.

Some of the women are participants and really wanted to do something. Some of them are there because they had nowhere else to go. And some are reluctant participants and are just waiting to let time pass so that they would feel comfortable about leaving the shelter and not really availing themselves of the services that the shelter offered.

One of the most distinctive features of all of the films of yours that I’ve seen is that none of those who pass in front of the camera ever seem to look at it. Do you ever worry that they’ve not only got used to your presence but are adjusting their behaviour for you camera, performing if you like for your benefit?

One of the reasons that you don’t see them looking at the camera is that, whenever it happens I have a cutaway, I cut it out. My experience is that, by and large, for reasons that I don’t fully understand, it’s very rare that anyone looks at the camera. I also don’t happen to think that people change their behaviour because they’re being photographed. I don’t think people have the capacity to act that differently. If they don’t want their picture taken or their voice recorded, they’ll say “No!”, or walk away, or thumb their nose or whatever. But if they agree, most people aren’t good enough to alter their behaviour because their picture is being taken. They can alter it in the sense of saying “No!” or walking away, but not in terms of putting on a performance, a different performance. Because if they could do that then there’d be a much larger pool of actors from which movies could be made.

Did it take long for the women to get used to your presence in the crisis centre, or did it happen spontaneously?

It happened instantly, and not just in that film but in all the films. I mean, there’s material in that film from the first hour of shooting. Again, I don’t know if there’s an explanation – and if there is one I don’t know what it is – but the fact of the matter is that that’s never been a problem for me. It’s never been a problem that I had to hang around for a while before people get used to the camera.

|

| Welfare |

In the shelter, or what you call a crisis centre, the staff and a lot of the women were there for a period of time and I saw them every day. In many of the films I’ve done – for instance, in Welfare [1975], the one I did a number of years ago about a welfare centre – the people were just popping in and out. They might, say, come in the morning and spend a couple of hours in the welfare centre and do their business and then leave. And that would be the only time that they were there. They had no idea in advance that a film was being made and yet the scenes in Welfare are just as intimate as the scenes in Domestic Violence.

Among the possible explanations are indifference, vanity, ah, media saturation… I don’t know that any one explanation, or any group of them, is adequate. It’s just that, in my experience, and I can’t speak for other documentary filmmakers, it’s simply not a problem. And the only thing I do to defuse it as a potential problem is to be very clear about what I’m doing and how the film’s gonna be used. I don’t bullshit people because I think their bullshit meter is going to be at least as good as mine.

I get permission from people, sometimes before the sequence and sometimes after it, and if they don’t agree I don’t use it. And if they thought I was conning them, they’d say “No”, or they’d get wary. But it’s very rare that anybody says “No” after the sequence has been shot.

But I don’t know if any of that is the explanation for how people become comfortable in the presence of the camera.

*****************************

PART TWO will b published shortly.

Sydney Film Festival is also screening a ten film retrospective devoted to the work of Indian master Satyajit Ray selected by David Stratton. Information on titles, times etc can be found IF YOU CLICK HERE

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.