Linda Darnell,

Dorothy Dandridge and Jean Seberg all met untimely deaths. All three did their

best work with Otto Preminger.

|

| Linda Darnell |

Darnell's co-star,

Alice Faye, a leading star of Fox musicals seeking change to a dramatic

role in Fallen Angel, said Preminger was “very tough to work with ...a

good director but a mean SOB. He got a lot out of me.” Faye recalled that

Darnell and Preminger “did not work well together, and made no bones about

saying so.” At Zanuck's behest they were

obliged to continue in combat on three more films.

|

| Dana Andrews, Linda Darnell, Fallen Angel |

It is true to say I

think that Preminger always had serious plans to become his own boss, achieving

independence in the industry setting up his own production company although

still subject to Zanuck's script and editing approvals in a distribution deal

with Fox. Preminger did have the means to break new ground in challenging the

censorship code with The Moon is Blue (1953) and racial discrimination

built into Hollywood norms with an all-black cast for the film of the Broadway

adaptation of Bizet, Carmen Jones (1954). He also took on the Breen

office in their concern over an “overemphasis on lustfulness” in the submitted

script. Preminger decided to make “a dramatic film with music rather than a

musical. He determined from the beginning that the black actors would be dubbed

with white opera singers.

|

| Dorothy Dandridge |

On the set

Preminger was described as “bullying everyone.” Dandridge took a stand after he

screamed at her and “gave him hell.” One of the cast members said that the

director made Dandridge angry deliberately, that she was “doing more than she

knew that she could do. And he brought it out of her.” At other times he seemed

needlessly disparaging, intent on humiliating members of the cast.

|

| Dorothy Dandridge, Carmen Jones |

At the same time

Fujiwara notes that James Baldwin commented that the absence of white people

from the world of the film “seals the action off , as it were, in a vacuum in

which the spectacle of color is divested of its danger...an opera that has

nothing to do with the present day, nothing really to do with negroes.”

The camera fluency and skills of Preminger's mise en scène in long takes

(Fujiwara notes that it does approach Preminger's ideal of a film without cuts)

aiding the opening up of the opera to grounding in some suggestion of contemporary

reality. Preminger acknowledged both Carmen Jones and Porgy and

Bess as fantasies “that nevertheless convey something of the needs and

aspirations of colored people.” In this they had a role along with Sirk's Imitation

of Life (1959), in foreshadowing the arrival of something approximating a

black cinema in seventies Hollywood and independent American cinema.

Dandridge was the first African American woman to be nominated for the Oscar for Best Actress. This was for her a plateau from which she descended, or rather 'fell'. Her affair with Preminger continued for some time but surrounded by career pressures and social prejudices the two of them were, she realised, writes her biographer Donald Bogle, playing “a game – I get him, he to lose me.” Although Preminger did seek to strengthen her financial security she understood, as Fujiwara quotes her biographer, that “Otto was another confrontation with a white man who would not follow through.”

Dandridge was the first African American woman to be nominated for the Oscar for Best Actress. This was for her a plateau from which she descended, or rather 'fell'. Her affair with Preminger continued for some time but surrounded by career pressures and social prejudices the two of them were, she realised, writes her biographer Donald Bogle, playing “a game – I get him, he to lose me.” Although Preminger did seek to strengthen her financial security she understood, as Fujiwara quotes her biographer, that “Otto was another confrontation with a white man who would not follow through.”

|

| Dorothy Dandridge, Porgy and Bess |

Preminger had a

long standing fascination with Bernard Shaw's Saint Joan. In 1956 he

acquired the film rights from the Shaw estate, hired Grahame Greene to write

the script and began an extensive international search for the actress to play

Saint Joan. He surmised that the publicity from such a quest would help

pre-sell the picture. Multiple auditions were held all over America and in

Europe, the final being in New York in October 1956 culminating in the

whittling down to screen testing of

three finalists. Preminger directed his infamous bullying tactics particularly

at Jean Seberg to which she stood up successfully until finally breaking down

in tears, Preminger then comforted her assuring her that she had done well. The

other two finalists were more polished but what won through for Seberg was her

sincerity.

|

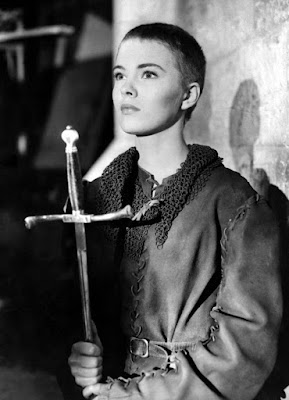

| Jean Seberg |

|

| Jean Seberg, Saint Joan |

If Seberg and

Preminger's filmmaking talents needing any vindication it has come with Bonjour

Tristesse which was again subject to a negative press at the time of its

release in America. On the set Preminger had reverted to form in giving Seberg

a hard time. She showed her toughness by just concentrating on following

instructions, even at one stage managing to send Otto up to his face. Over the

years the critical reputation of Bonjour Tristesse has continued to

grow. Seberg's reputation was further enhanced

by her performances in Breathless (1960) and Lilith (1965).

When Preminger sold his contract with her to Columbia in August 1958 she

lamented “he used me like a Kleenex and then threw me away.”

|

| Jean Seberg, Bonjour Tristesse |

David Thomson has

suggested of his life, that there is a Preminger movie in there. At core there

are the unresolved contradictions between the experience of the finished film

and what we know about the manner of their realisation, between the mise en

scène and the fluctuating extremes in his direction of actors (3). Preminger's

liberal instincts are evident in his direction, a concern with balance, in

placing character in context and the avoidance of the passing of easy

judgements. What fascinates in Preminger's genre films at Fox, for example, is

the dialectic between the material and his treatment of melodrama “with an

extraordinary lack of hysteria” to quote Thomson, who further adds that

Preminger is alone among Hollywood directors in triumphing in that genre “by

deflecting it” to the point of “easing in the direction of documentary.” This

was in sharp contrast to his frequent resort to bullying tactics on the set,

sometimes in a controlled way, at others he would seem to lose control out of

frustration or simply the overweening desire to impose his will, probably a

combination of both.

1.

Short biography of Darnell in Fandango,online. Suffering

severe burns to from 80 to 90 per cent of her body including her face,

she lived for thirty three hours after being rescued from the hottest part

of the fire.

2. See the Wikipedia entry on Dandridge for an outline of

the mysterious circumstances surrounding her death.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.