There are two things to draw us to Iranian Film Events, finding excellent titles like Through the Olive Trees or Manuscripts Don’t Burn and the fact that in the days of fake news and viral video they are the on the way to being the best guide to what that society is like. They’d be even better if the organisers didn't exclude the popular entertainments which the home public enjoys. That’s not what the film festival audience is buying apparently.

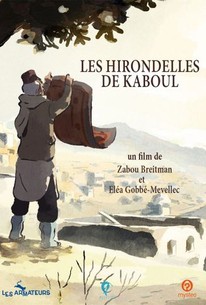

This year’s event would be justified alone by their screening of Les hirondelles de Kaboul/The Swallows of Kabul, from actress director Zabou Breitman and animator Eléa Gobbé-Mévellec, which has been drawing crowds in the Paris multiplexes.I’m still a bit confused by a Persian film festival running a French circuit house success set in Afghanistan but let’s not quibble.

In parched, hand painted images of 1998 Kabul under the Taliban, we see two incidents, a tumbler of water is pushed through prison bars and, on his way through the streets filled with Kalash wielding soldiers and blue burka women, Mohsen a young man voiced by Swann Arlaud passes the stoning of a woman convicted of licentious living. Children are climbing onto a parked tank to watch and Mohsen finds himself joining in.

Full of self-reproach he comes back to his building where wife Mussarat (Hiam Abbass no less) desperate at being confined to her home in his absence is drawing on the wall and playing an English language song about burkhas, on the cassette machine. Mohsen warns her that the music can be heard in the street or by their Observant neighbour. They briefly recall life before the cinema was destroyed and the book store looted and plan an outing with Mussarat wearing a spare blue burka borrowed from the neighbor.

Across town there is another homecoming. Hard man jailer Atiq (Simon Abkarian) has limped back to Zunaira (Zita Hanrot) the nurse wife who tended his leg wound and is now herself dying of cancer. They are aware that the regime they serve is incapable of providing them happiness. Don’t ask me what the swallows signify.

The plot develops into shock value melodrama distanced by being presented in pale water colors and the fact that Afghans are speaking sub-titled French. We know that we are watching special pleading like Captain Phillips or Balzac and the Little Seamstress but none of this stops what we are seeing being disturbing. It arrives with plausible detail - female prisoners can only be tended by gun wielding burka women, white shoes punished by having the husband dragged into the mosque to listen to Mulla’s sermon, public executions in a segregated-by-sex football stadium.

We can only hope that this is not the last we see of this film.

Parviz Shahbazi’sTalla/Gold (poster left) does evoke the texture of Tehran life. Houman Seyyedi is dismissed from a construction job where he hasn’t been paid for months and has to drive a cab. His lady friend doesn’t tell him she is pregnant and his little girl is likely to develop curvature of the spine.

Parviz Shahbazi’sTalla/Gold (poster left) does evoke the texture of Tehran life. Houman Seyyedi is dismissed from a construction job where he hasn’t been paid for months and has to drive a cab. His lady friend doesn’t tell him she is pregnant and his little girl is likely to develop curvature of the spine.

In a pub showing a football match on its flat screen TV, he meets a group of friends also leading unsatisfying lives and they decide, like the characters in Duvivier’s La belle équipe, to start a business together with a Soup Restaurant. They hit bureaucratic hurdles and their financing, involving ballet with the books on one girl’s buyer’s job and another’s family business, goes South - at which point the piece turns into a people smuggling

melodrama.

This one has moments of conviction in its picture of Tehran - the musician’s cafe, currency trading, military service cards, obstructive bureaucracy and underpaid workers. The cast do their best and the film-making manages a professional texture. Things are not helped by the fact that women in head scarves and bearded men tend to look the same (that's the idea) making the piece even harder to follow.

Haft va nim/Seven and a Half (poster right) is a new Persian language film from the Mahmoudi Brothers whose films are regularly put up as the Afghan entry for the Academy Awards. Their subject is the Afghan-Iranian experience with many Afghans moving to the country, often as a way station to European destinations.

Haft va nim/Seven and a Half (poster right) is a new Persian language film from the Mahmoudi Brothers whose films are regularly put up as the Afghan entry for the Academy Awards. Their subject is the Afghan-Iranian experience with many Afghans moving to the country, often as a way station to European destinations.

Director Navid Mahmoudi’s film is made up of seven vignettes each one featuring a distressed young woman battling the demands of their society built around an intimidating concept of marriage. These include the dress shop worker distraught

because her fiancé’s mother insists on accompanying her to a gynecologist to see if she is “still a girl” as the timid sub-titling puts it. Fereshteh Hosseini is found on the table in the indignant woman doctor’s surgery when her husband breaks in to interrupt

her procedure. Anahita Ashar makes her way down an alley to the builder she had paid to marry her so she could get papers and emigrate to her lover in Germany. The man is demanding his husband’s rights before he will divorce her. A trans-sexual interrupts her dad, in front of his work mates in a dairy, to tell him her arranged marriage will be a calamity. In a flower market, the lover of a thirteen year old finds that her father has lost her in a card game. We end with the girls being driven to their disastrous nuptials.

Each of the seven stories are recorded in a single run of the Arri 4K digital camera which provides a muted colour image occasionally undermined by missing a change in exposure, an extra walking through the shot determinedly not looking at the camera or the question of how they are going to continue when someone closes the door. That’s where the cut comes, curiously similar to John Farrow’s long takes back in1946 for California.

The film’s earnestness and high purpose mark it as a contender for art film distribution which may be undermined by its seventy five minute length. With several festival films running close to only an hour, double features would have been a way

to ease the financial strain.

Kourosh Ataee and Azadeh Moussaka’s 2018 Dar Jostojoy-e Farideh / Finding Farideh (poster left) comes with the official endorsement of being the first documentary that Iran has put up for the best film Oscar.

Kourosh Ataee and Azadeh Moussaka’s 2018 Dar Jostojoy-e Farideh / Finding Farideh (poster left) comes with the official endorsement of being the first documentary that Iran has put up for the best film Oscar.

Eline Farideh Koning was abandoned as a baby in a Tehran temple forty years back and adopted by a Dutch couple. Unhappy with the loss of identity that has come with

her life in Holland she has used Skype to try to find her birth family, getting three (!) takers. The film follows her preparation, studying language & customs and her journey to Iran to meet them, with DNA testing to establish the real connection.

There are professional production values and a substantial secondary theme in showing the contrast between the urban Iranian families and the one from a rural village where they still practice polygamy and the mother keeps pulling her head scarf over Farideh Koning’s hair. Her presence opens old wounds - four generations of drug addicts, unforgiving fathers, mothers still in grief. It has touching moments and glimpses of Iranian - and Dutch - life. Shots like the quick view of the back of the subject, as she weeps, do involve.

The suspense of getting the test results is effective and it’s appealing that even the rejected families still welcome the subject as their own.

Unfortunately the stamp of Reality TV is heavily upon all this, as if the lead and contrasted aspirant families had been the result of a casting call, along with “Now I can let my own pain go” first person narration.

|

| Shouting at the Wind |

Also non-fiction (it’s hard to recognise these from the program booklet) was Siavash Jamali and Ata Mehrad’s Shouting at the Wind, another effort in the style of what used to be cinema-verité.

The camera follows teenage boy Meysam, from the impoverished Darvazeh Ghar district. His dream is to be an underground musician in a country where the music his life centers on is frowned upon. “It’s the land of the dead.” We see the difficulties of his day to day life in an area used by petty criminals and addicts and his training with a classical singer. Iran’s fractured relationship with the U.S, is inescapable - Obama on TV, “Why were they listening to Pink Floyd?”

The handling is pro and it’s possible to empathise with the subject but a hundred minutes is stretching their luck.

There was no Through the Olive Trees or Manuscripts Don’t Burn in what I saw but as always, I could have missed the highlights. Documentation is scarce and these events are too expensive to explore fully. The advertised three pass ticket proved elusive. That said, Iranian film remains a particularly intriguing subject with its generational gap, tension with authority and it’s struggle for a voice of its own. I’ll be back for another one.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.