|

| John Conomos |

Cinephilia is such

a complex, dreamy, life-shifting experience like clouds forever changing their

shape. And, like clouds, cinephilia can keep one entranced through one’s

circuitous life journey. Trying to select your ten best first films is akin to

trying to freeze frame your life’s memory-laden feelings, experiences and the

countless encounters one has with the cinema in their public and private,

fugitive moments of existence.

As a parlour game

trying to work out which of a director’s films came first and when and where,

seeking out their half-forgotten filmographies is worthy of Vladmir Nabokov’s

playful forensic temporal imagination. So one’s list will inevitably recall

some of the selected films by the previous participants to this parlour game.

Hence Terence Malick’s Badlands

(1975), Andre Delvaux’s The Man Who Had His Hair Cut Short (1967 and one of J. G. Ballard’s own favourite

directors), Jerzy Skolimowski,’s Walkover

(1966), Errol Morris’s Gates of Heaven (1978) - the list can be

quite endless, but in this context I have mentioned a few examples that fellow

cinephiles Bruce Hodsdon and Tina Kaufman have recently listed in Film

Alert 101. How else can it be different given that all of us one way or another

have been immersed in cinema, in the main over the years, as a communal-going

experience with the ever–hypnotising cone light dancing above our heads in the

darkened realm of a movie theatre?

Since the mid

1950s as a young kid I have been watching movies in cities like Sydney, London,

Paris, New York, Athens and elsewhere and besides the usual art cinemas of

these cities, film festivals, NFT (Australia ), university film societies and

clubs, WEA, etc, I must include that, for me , my own cinephilia also is

seriously indebted as well to watching cinema on late night television in

Sydney in the 1960s and onwards. In this specific context, my mother who was a

Hollywood classic cinema fan encouraged me to follow my passion for films.

Hence, if I may say so, one substantial reason why I have become such a chronic

insomniac.

For my first-time

feature films selection what follows is, certainly, not cast in stone but may

vary according to my memory, biography, feelings, time and place.

|

| Werner Herzog |

Werner Herzog: The two earliest narrative feature films of Herzog’s

that come to mind are Signs of Life (1968)

and Even Dwarfs Started Small (1970).

Both tend, over the years to intermingle with each other, but I do recall

seeing the former film with together with Barrett and Bruce Hodsdon one hot

sweltering summer’s day. As for Herzog’s

documentaries I first saw Fata Morgana

(1971) at the Opera House, then I caught up much later with his early third

documentary Land of Silence and Darkness

(1971).

|

| Errol Morris |

Errol Morris: Gates of Heaven

(1978) : Morris’s documentary about a pet cemetery embodies the director’s

surreal approach to filmmaking but it was ten years later with his very

critically acclaimed The Thin Blue Line (

1988), (1977) Morris established his

major status as an auteur concern with the experimental postmodern potential of

the medium itself.

|

| Terence Davies |

Terence Davies: Distant Voices,

Still Lives (1988) Davies’s poetic masterpiece about a working class family

in Liverpool in the 1940s and 1950s incarnates the director’s abundant resonant

creative imagination as a screen –writer director. In 2008 Davies ‘ lyrical

essay documentary about Liverpool “Of Time and the City “ is not to be missed

as is his more recent accomplished narrative feature about the American poet

Emily Dickinson A Quiet Passion (2016).

|

| David Lynch |

David Lynch: Eraserhead (1977) First saw it at the Valhalla Cinema,

Glebe. My first reaction to this cult surreal horror film was “What in the

world was that?” Saw it about five times in the first year of its general

release. Lynch, like the three preceding directors, is an uncompromising

horizon-expanding artist and in Lynch’s case his oeuvre is always alert to the

intertextuality of cinema, painting, and drawing.

|

| Michael Oblowitz |

Michael Oblowitz: King Blank

(1983) Oblowitz’s ‘New York Wave” is a

far-reaching cult examination of modern alienation and heterosexual couples

that transcends genre amounting to an existential biopsy of the human

condition. Unforgettable.

|

| (the young) Aleander Kluge |

Alexander Kluge: Yesterday Girl

(1966) was one of the defining New German Cinema films of its era “This film

tells of the social and psychological problems that its female protagonist

experiences from migrating from East Germany to West Germany. Kluge’s rigorous

post-Brechtian reflexive style of filmmaking is very unique in European art

cinema. Kluge is one of the few public

intellectuals (television, literature, philosophy) of European art cinema.

|

| Theo Angelopoulos |

Theo Angelopoulos: The Travelling

Players (1975) Strictly speaking, the highly acclaimed The Travelling Players which is Pt 2 of the director’s Trilogy of History, was the

first feature film of Angelopoulos that I saw, then I caught up with his debut black

and white feature Reconstruction (1970)

and two years later Days of 36.

|

| Bernardo Bertolucci |

Bernardo Bertolucci: Before the Revolution (1964) Again, this film was not Bertolucci’s

directorial debut film. That was The Grim Reaper two years before but it was the first feature

that I saw in the 1960s and early 70s before anything else of Bertolucci’s.

|

| Chantal Ackerman |

Chantal Akerman: Akerman’s oeuvre covering both her films and

installations, like Agnès Varda, and to a much lesser extent Sally Potter, is

something fairly dear to my trajectory as a cinephile. (Both Akerman and Varda truth

be told have both film played their respective vital roles in contributing to

the aesthetic, cultural and historical features of my cinephilia. In Akerman’s

case, I saw her internationally acclaimed Jeanne

Dielman , 23 Quai Du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles ( 1975) – that has Henri

Storck, the pioneering Belgian filmmaker

in a cameo role in the film -

about the same time I saw her 1972 Hotel

Monterey and, much later on I saw Akerman’s other internationally acclaimed

film The Golden Eighties (1983) when

it was first released.

|

| Jacques Rivette |

Jacques Rivette: Of all the

French New Wave directors, it was Rivette’s first feature film Paris Belongs to Us ( 1961) that I saw a

few years later in the 1960s that had,

along with Godard’s Breathless

(1960) , such an impact on me as a cinephile , like it did for many of my

immediate peers of that generation. First began in 1958 Rivette’s film has all

the classical tropes of his approach to the cinema: improvisation, long takes, paranoia,

and ‘house of fiction’ aesthetics that explore often the intricate nexus

between the cinema, literature and most particularly the theatre.

|

| Paul Schrader |

Paul Schrader. Blue Collar (1978) Schrader’s film was written by him

and his brother Leonard and it is a powerful,

highly kinetic crime drama dealing with union practices and issues

located in a working class ‘rust bucket’

locale. Schrader as a director, screenwriter, and producer who has contributed

in such significant terms to other directors including Martin Scorsese, Brian De

Palma, and Sydney Pollack, amongst others , wrote in 1972 “Transcendental Style

in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer” , which was a very influential book in shaping

my cinephilia regarding these three giants of world cinema. A fellow cinephile

recommended I look at it when it first came out. Which I did reading it

virtually in two sittings.

|

| Victor Erice |

Victor Erice: His small but poetic oeuvre should also be noted on

this list. Particularly The Spirit of the

Beehive (1973), a painterly haunting

study of a young girl’s fascination for James Whale’s 1933 horror classic Frankenstein and its impact on her

family life including schooling, etc.

Also, we need to mention his masterly reflective short narrative

documentary film The Quince Tree Sun (1992) about a painter and the things that matter to

him in getting his painting done like the weather, light, etc . It is hard to

believe that it has been ten years since Melbourne’s ACMI put on a brilliant

exhibition “Correspondences Victor Erice

and Abbas Kiarostrami “ concerning itself with Erice’s fragile, poetic and

illuminating small oeuvre and Kiarostrami’s films and installations since the

1990s. It made him a master (like Erice) of world cinema. I saw the enchanting

show together with Adrian Martin. One was absolutely dumbstruck by the simple

lyrical beauty of the show and its immense importance to cinema as we know it

today.

|

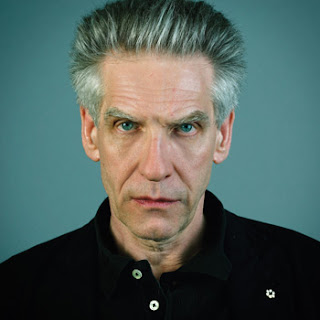

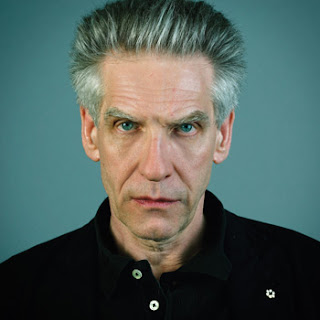

| David Cronenberg |

Finally, in terms

of horror/ exploitation/ independent cinema, two directors whom I encountered in

the 70s were the Canadian David Cronenberg and Larry Cohen. With Cronenberg the

feature that spoke to me of his ample talents as a writer/director shaping

horror was Shivers (1975 ) and two

years later Rabid (1977) of which one

of the earliest screenings I

saw was in San Francisco in a flea-pit theatre with a black American audience.

Quite an experience it turned out, for me and Carol to see the spectators in

question riffing and intervening with meta-commentary about the film, its

characters, plot, etc.

|

| Larry Cohen |

And with Larry Cohen, after seeing his early

two films Bones (1972) and Black Caesar (1973) in NYC in the late 70s, I then, also in NYC at MoMA, caught up with a Cohen retrospective season. There I can recall the American/Cuban critic Carlos Clarens

standing up and questioning Cohen on the thirties and G-man films, etc . Thanks to Robin Wood and Tony

Williams, Cohen’s cinema became more critically recognizable.

John Conomos,

Monday 22 January 2018.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.