I invited Bruce Hodsdon to contribute to this dossier assembling exercise and he responded in a most thoughtful way thus: Having

come seriously to cinema surfing on the New Wave (especially taking in

Truffaut's political assault on Cinema de Papa translated in the short lived

Cahiers du Cinema in English) I consigned Duvivier to journeyman status on the

slimmest of first hand evidence. David Thomson's later dismissal in his bio

dictionary ("a man who managed to always look spruce but seldom original

or interesting...displaying a cyclical complacency in remaking several of his

own films" ) did not encourage reappraisal. One of course wonders how many

of D's films DT has actually seen - he singles out about a dozen - none for

anything that can be construed as positive comment beyond commercial

success. D is taken to task by Thomson for his failure "to celebrate

beautiful women" - "an uneasy " Vivien Leigh in Anne

Karenina and subsequently Darrieux , Arnoul and Presle.

Now I've received the note below which draws upon some of the keys texts on classical French Cinema.

Julien Duvivier

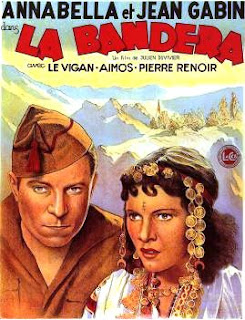

Key films: David Golder (31); Poil de carotte (32); La

Tete d'un homme (33)*; Maria Chapdelaine (34); La Bandera (35)*+; Pepe le Moko

(36)*+; La Belle equipe (36)*+; Le Fin du jour (37)*; Un Carnet de bal(37)*;

Panique (46); Voici le temps des assassins/Deadlier Than the Male (56)*+

*also co-script. +

with Jean Gabin.

It is surprising to find Sam Rohdie making

the case for Duvivier as a superb craftsman, finding more thematic

consistency than has been generally acknowledged, including thematic accord

between Duvivier's and Rossellini's films.

Rohdie was interested in writing that produces paradoxes, no

better illustrated than in his monograph on Antonioni, the most provocatively

interesting I have read on the films of that director. One looks forward to

Rohdie's last work, Film Modernism, to be published next month (September

2015), to which the Duvivier essay seems related. It does, however, fall short

in the placement of Duvivier's eclecticism, most notably failing to acknowledge

Dudley Andrew's analysis of the nature of Duvivier's central role in poetic

realism that stands ambiguously apart from his other work. This is developed

more fully in Andrew's book Mists of Regret written ten years

after his summing up, excerpted below from The International Dictionary

of Cinema (1984), that might best be summed up in Andrew's phrase quoted

below, describing Duvivier as a skilled and committed “yeoman of the industry”.

“No one speaks of Duvivier without apologising. So many of

his 60 odd films are embarrassing to watch that it is hard to believe that he

was ever in charge of his career in the way we like to imagine that Renoir and

Clair were in charge of theirs. There is justice in this response. Duvivier had

neither the luxury nor the contacts to direct his career...Duvivier began and

remained a yeoman of the industry.”

Duvivier made over a score of silent films, commercially

successful, but mostly otherwise undistinguished melodramas.

“His reputation jumped as a reliable, efficient director when

he made a string of small but successful films such as David Golder and Poil

de carotte in the early years of sound. Evidently his flair for the

melodramatic and his ability to control powerful actors put him far ahead of

the average French director trying to cope with the problems of sound. But in

this era, as always, Duvivier discriminated little among the subjects he

filmed”.

But in the mid thirties Duvivier hit his stride with La

Bandera (France, 1935):

“Its success was the first of a set of astounding films

including La Belle equipe, Pepe-le-Moko, Un Carnet de bal

and Le Fin du jour...Like Michael Curtiz and Casablanca, Duvivier's

style and the actors who played out the roles in his dramas spoke for a whole

generation...vaguely hopeful of the popular front, but expecting the end of the

day. Duvivier’s's contribution to these films lies in more than the direction

of actors. Every film contains at least one scene of remarkable

expressiveness...Duvivier's sureness of pace brought him a Hollywood contract

even before the Nazi invasion forced him to leave France.

“Without the strong personality of Renoir or Clair, and with

far more experience in genre pictures, Duvivier fitted in well with American

methods. (Yet) he deplored the lack of personal control or even personal

contribution. But he acquitted himself well until the Liberation.

“Hoping to return to the glory years of poetic realism, his

first postwar project in France, Panique, replicated the essence of the

style: sparse sets, atmosphere dominating a reduced but significant murder

drama...The film failed and Duvivier began what would become a lifelong search

for the missing formula... Only Camillo with Fernandel put him in the

spotlight.

“Believing far more in experience, planning, and hard work

than in spontaneity and genius, he never relaxed. Every film taught him

something and, by rights, he should have ended a better director than ever. But

he will be remembered for those five years in the late 1930s when his every

choice of script and direction was in tune with the romantically pessimistic

sensibility of the country.”

“Duvivier is often accused of being eclectic, if highly

competent craftsman who bought little personal commitment to his work. He

typically found his subject matter in popular fiction, and his cinematic style

could vary enormously, depending on his material.”( Alan Williams).

Although on the right of the film industry politically, it is

debatable how much this is reflected in Duvivier's films especially La Belle

Equipe with its focus on working class unemployment made around the time of

the Popular Front. Apart from Jean Renoir's Popular Front films, on the left

the films of committed socialist Jean Gremillon, for example, are considered to

show no more signs of political orientation than Duvivier's, with which

Gremillon's films share a poetic realist sensibility.

Duvivier saw the work as imposing the style on the director

and not the other way round. His only concern was to bring out the spirit and

character of each subject and compose an appropriate atmosphere.

|

| Gabin and Annabella, La Bandera |

Despite his pragmatic choice of subjects and eclectic

approach to style, a recurring thematic interest has been discerned in his oeuvre:

the often tragic plight of isolated individuals, something Duvivier shared with his contemporary, Jacques Feyder,

but placed more directly by Duvivier in social context. There were defining

roles for Jean Gabin whom Duvivier directed ten times. In two of Duvivier's

best films, Pepe-le-Moko and Le Fin de jour, the central

character is in exile.

Duvivier was a

consummate craftsman who “showed an astonishing precision: even before placing

his actors he could tell you where he wanted the camera, the dimensions of the

support and the type of lens ...he had it all in his head.” (cinematographer

Michael Kelber is quoted by Colin Crisp).

Although in outlook Duvivier's professionalism and pragmatism

seemed in accord with the Hollywood studio system, he found the strict division

of labour meant he had much less overall control than he enjoyed as a director

in the French system.

Dudley Andrew discusses Duvivier's career at greater length

in his near definitive Mists of Regret: Culture and Sensibility in

Classic French Film (1995).

See also: Republic of Images, A History of French

Filmmaking by Alan Williams (1992) and The Classic French

Cinema,1930-60 by Colin Crisp (1997).

For those of you who are interested may I direct you to a most informative exchange and fellow cinephile and scholar David Hare which is on my Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/geoffrey.gardner.5

ReplyDelete