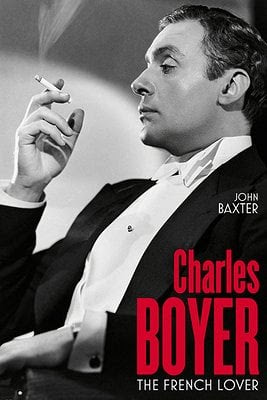

Early in Charles Boyer’s Hollywood career, director Gregory La Cava asked him “Do you think in English or French?”

Boyer replied that, though he was playing in an American film, he still thought in his native language.

“There’s your problem,” said La Cava. “Until you learn to both think and act in English, you’ll never make it in pictures.”

During a long career in which he won acting honours in both Europe and the United States on screen, stage and television, Boyer often quoted this story. For a time, he tried to follow La Cava’s advice, but finally came to believe that, in whatever language he acted (and Boyer was fluent in five of them), he would remain always, mentally and emotionally, French.

For generations of film and theatre audiences, Boyer was the archetypal Frenchman, cultivated, courteous, seductive, yet never quite at home in a culture not his own. The sense of loss conveyed in his murmuring baritone voice was the very essence of romance. Women longed to comfort him, men to become his friend.

One would not have been surprised to find that the real life Boyer was a playboy and serial seducer. In fact, he was intensely private, thoughtful, and both intellectually and political astute. Nominated four times for Academy Awards, he was honoured by the Academy only once, for his activities on behalf of France during World War II. Married to the same woman all his life, he was so devoted to her that, two days after her death, he killed himself, the dying fall of an often tragic life during which he lost his only son, also to suicide.

It’s arguable that Boyer’s refusal to commit himself completely to any one language or medium was the secret of his remarkable success.

Having established himself as a jeune premier in the theatre and cinema of France, he sailed confidently through the transition from silent film to sound, made his name as a romantic leading man in Hollywood during the 1930s and 1940s, adapted to postwar character roles in both Europe and the United States, entered television in the 1950s as both producer and performer, and would, one feels, have gone on indefinitely had not personal tragedy intervened.

Even after death, an aspect of his talent survived, in the form of his distinctive voice, which animator Chuck Jones co-opted for the character of Pepé le Pew, the seductive skunk of the Oscar-winning cartoon series.

Far from clinging to the performances that made him famous, Boyer showed a readiness to break the mould. After playing the doomed Continental lover in Algiers, he was a credible Napoleon in Conquest opposite Garbo, re-emerged in the sentimental comedy romance Love Affair, only to remake himself once more as the malevolent manipulator of Ingrid Bergman in Gaslight.

His choice of roles during and after World War II shows a shrewd perception of his image. Realising his accent would always mark him as an outsider, he embraced that trope but also subverted it In Hold Back the Dawn, he was a European gigolo loitering on the Mexican border, ready to seduce some tourist into marrying him, a role he reversed in Arch of Triumph as a principled Austrian doctor, stranded in Paris with little hope of evading the advancing Nazis.

At a time when actresses were expected to swoon into the arms of their male lovers, Boyer more often chose leading ladies who declined the submissive role in their relationship. Irene Dunne was his foil in Love Affair and Ingrid Bergman a worthy adversary in Arch of Triumph and Gaslight, while in The Garden of Allah Boyer’s character is the plaything of women, first of Tilly Losch, who vamps him in a memorably erotic dance, then of the supremely confident Marlene Dietrich.

Boyer appeared frequently on stage both in the United States and France, put his career on hold during World War II to become politically active on behalf of his occupied home country, and remade himself as a comedy performer in the 1960s, as much at home, it seemed, playing slapstick in I Love Lucy as in Neil Simon’s sophisticated Barefoot in the Park opposite Robert Redford and Jane Fonda.

***************

Editor's Note:John Baxter is an Australian-born all-round writer, scholar, critic and film-maker who has lived in Paris since 1989 with his wife Marie-Dominque Montel and daughter Louise. His Wikipedia entry details the many books he has written which include the first ever critical volume devoted to the Australian cinema as well as studies of Ken Russell, Josef von Sternberg, Stanley Kubrick, Woody Allen, Federico Fellini, George Lucas, Robert De Niro and Luis Bunuel. His most recent book, one of a number of studies of Paris is A Year in Paris, described by the New York Times thus "In “A Year in Paris,” (Baxter) strings together the beautiful beads of the French everyday, all held together by the invisible act of imagination that makes a country cohere and endure."

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.