In the beginning

I didn’t come to Wong Kar wai’s films by way of his most popular, or most loved film - Chungking Express (1994); but by way of his lesser known Hong Kong city sequel, Fallen Angels (1995) that served as an epilogue to the carefree imaging/imagining of a contemporary Hong Kong we were about to lose.

I fell in love with Fallen Angels when I first saw it at the Academy Twin back in the day; yes, it had a theatrical release in Australia (maybe in 1996?). I was immediately mesmerised by the poetry of Wong’s cinema, entering into his filmic world, one is awestruck by a sense of nostalgia - of a Hong Kong I love and have dearly missed - that as soon as I left the cinema, I went and bought a ticket for the next session to see it again. This is something that I had not done before, or since. Incredibly, this singular experience also lead me to do my honours degree on this director the following year. I then subsequently received a scholarship to do my PhD on Wong’s films, broadening and deepening this fleeting feeling: of memory, love and nostalgia; with the philosophies of Bergson, Barthes and Deleuze.

Watching this film again, 25 years since I last saw it on the big screen, I found that the film had not aged, but I have. I now experienced something beyond what I first felt in that initial viewing: there is a strong sense of an ending in this film; an ending to youthfulness, of a freedom and the era that was Hong Kong.

|

| Michelle Reis as the killer’s partner in a labyrinthine interior of Fallen Angels |

Sure, I knew this even when I did my honours thesis all those years ago, the first sentence of chapter one: “The State of Disappearance: Hong Kong in the mid 1990s was experiencing the state of its own disappearance.” But to see it from the perspective of hindsight, Wong’s melancholic images had a prophetic lyricism that is heart-breaking.

I am a child of crisis and polyphonic historiography

Chungking Express, Fallen Angels and Happy Together form a cryptic trilogy of contemporary Hong Kong; there is a sense of speed and movement in these stories that are intricately linked together. What surfaces from these films is that the identity of Hong Kong contains multiple repertoires - Hong Kong people are borne in a city that boils over with languages (Cantonese, Mandarin, English, Japanese, Shanghainese and Portuguese) and cultural syncretism. Being from this land, my identity is always already polymorphic. For the closing chapter of this triptych, Wong had to leave Hong Kong, all the way to Buenos Aires to finish his series aboutHong Kong. Perhaps this self-exile is needed to reconcile the events of 1997; what was about to happen can only be internalised and not voiced.

|

| Leslie Cheung and Tony Leung ’s exiled lovers, stranded in Buenos Aires in Happy Together |

However, it is also in these three films where we find Wong at his most free; accentuated by a loose narrative structure, with most actors only receiving a page of script at the start of the day, the rest improvised on set (Tony Leung only had 10 days for the shoot of Chungking Express as he was recording his album at the time); and coupled with the now legendary camera work of Christopher Doyle which liberates the viewer from the confines of establishing shots, or shot / reverse shots standards; by giving us glimpses of the characters through doorways, between slits, or in the extreme close-ups. These shots may have been a result of working in confined spaces, but the artistry of movement are balletic, creating a kind freedom, a spirit and lightness which permeated this trio of films.

|

| Doyle’s ‘gonzo’ cinematography is pure poetry |

The benefit of having grown up in Hong Kong as well as being a native Cantonese speaker keys you into a sonic universe that is vital to the layering of its characters. Maybe all this doesn’t matter when you can simply enjoy the new aesthetics and the somewhat quirky narrative journey on which Wong’s films take you, especially so with Chungking Express and again with the idiosyncratic characters that populate Fallen Angels. Is it of any importance to know that Takeshi Kaneshiro is a huge Taiwanese star of Japanese des3cent, who speaks Cantonese with an accent? Or that Faye Wong hasn’t acted prior to her role in Chungking Express, but is already a superstar and pop icon with sell-out stadium shows? Or that the song that shot her to stardom was a Cantonese remake of ‘Dreams’ by The Cranberries’? The original version was about a first love; whereas Faye’s version of ‘Dreams’ actually translates to ‘Dream Lover’, 夢中人, that is, the person whom one can only think about when lost in a daydream, or sleepwalking through life. Remember all those references in the film about ‘daydreaming’ and ‘sleepwalking’ in Chungking Express? Her version was the one used during the scene when Faye was watching Cop 663 drink his black coffee at the food stall in slow motion, whilst the foreground was a blur of movement. Or, is it of any consequence to know that it is actually not unusual for Hong Kong actors to also be huge pop singers? Tony Leung, Leslie Cheung and Leon Lai are prime examples of this cross-over.

|

| Faye Wong’s character daydreaming about love in Chungking Express |

Perhaps all the culturally syncratic nuances can be missed without any affect, but the phonetic wordplay across Wong’s films are his private jokes with the viewers; take for example Faye Wong’s character name is ‘Fei’ - for a native speaker, it immediately conjures up two words phonetically - ‘fei zai’ meaning a rebellious youth, and ‘fei’ meaning ‘fly’ - to take off somewhere - which was what her character ended up doing. Takeshi Kaneshiro’s character (detective 223) in Chungking Express is called ‘Mo’, which phonetically means ‘emptiness’ or ‘void’. When he was on the pay phone looking for a date, he was always saying this is ‘ah mo’ calling; which literally meant it’s the person who is always empty-handed calling. This is especially funny when he repeatedly fails to get a date. In Fallen Angels, although his character had a different name, he was first introduced when the killer’s unnamed partner was shown his photo by the police; and asked as to whether she had seen this man; and she replies ‘mo ah’ - meaning ‘I haven’t’ - sonically recalling his earlier character in Chungking Express. And later, Tony Leung’s character in In the Mood for Love also has this word in his name, Chow Mo Wan. This word delivers a wry smile on my face when I realise that the word ‘mo’ also conjures up my favourite mot du jour, as ‘mo’ is also the phonetic twin of the word for ‘dance’ in Cantonese.

|

| Takeshi Kaneshiro’s Cop 223 is a romantic at heart and later falls for a suspect; Chungking Express |

Another private joke and more doublings

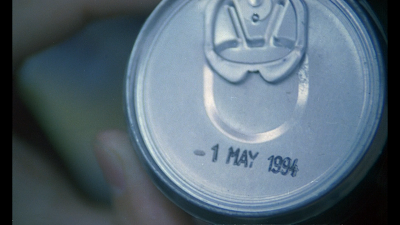

In Fallen Angels, Kaneshiro’s character is a mute who claims he lost his voice at the age of 5 after eating an expired tin of pineapples; recalling a favourite scene of Wong’s fans from Chungking Express - of Cop 223 eating 31 tins of pineapples all with the expiry date of 1 May 1994 to commemorate May’s birthday (pineapple was her favourite fruit), but also to mark her break-up with him. Add to this, another the repetition of the ‘blonde haired woman’, where in Chungking Express the raincoat and sunglasses-wearing drug runner in a blonde wig is reminiscent of Cassavetes Gloria; whilst in Fallen Angels - there is both a blonde girl, who had dyed her hair that colour to be more ‘memorable’; as well as a girl who was seeking a ‘blondie’ who had stolen her lover. And this ‘blondeness’ also manifested itself onto Takeshi’s character - his hair turning blond after falling in love with the latter character, as though symbiotically dependent - all this gets a good chuckle out of the audience.

|

| Brigitte Lin in Chungking Express – a tribute to Cassavetes’ Gloria and ‘on blondeness’ below from Fallen Angels |

Delving deeper, however, the Cantonese title of Chungking Express 重慶森林 is a composite word, 重慶 (Chungking) and 森林 (jungle); on the one hand 重慶 can refer to Chungking (Chongqing) one of the major municipalities of China; or for a Kowloon local, the Chungking Mansions that is notoriously dense with many ethnicities and characters; whilst 森林 (jungle) can be a description of the labyrinthine corridors of this building complex. Phonetically, however, 重慶森林 evokes the words ‘a jungle of heavy-heartedness’ which can come to describe the state of Hong Kong people with an uncertain future.

But unlike Herzog’s jungle of Aguirre,which is filled with, and I quote, “strangulation and fornication”, the jungle of Wong’s Hong Kong is filled poetry and the dreamic; and its denizens’ dance evokes the essence of this unique place. Whether shown in the now famous ‘step printing’ opening sequence of Chungking Express when Cop 223 literally runs into the drug runner, with only ‘0.01 cm’ that separated them; or the slow-motion black and white sequence in Fallen Angels of Kaneshiro’s character seated next to Charlie Yeung’s character (the girl seeking blondie); both are looking in opposite directions behind a rain-washed window pane, we see this mesmeric dance - of his sweet face circling around her repeatedly like a butterfly to a flower, but without actually touching her; he gets to be close to her by inhaling her scent with closed eyes.

|

| "...inhaling her scent with closed eyes.." |

Even the choreographed shootout sequences in Fallen Angels with the meandering and vertiginous temporal cross-cutting of the two partners casing out the same joint makes you spellbound; or the waltz between Mr Chow and Mrs Chan when they traverse up and down the staircase to the noodle stand in In the Mood for Love; you find that Wong’s world is inhabited with lingering moments of beauty.

|

| The nearness of you… In the Mood for Love |

These doublings, triplings, and encounters bleed and leak from one film into the next, one character into another; the interiority of the body narrative becomes the interiority of a city, its meanderings, labyrinthine and incomprehensible - the passcodes and obligatory numbering of its citizens - it is a jungle that crisscrosses not only spatially, but also temporally.

Interior temporality (after Jean-Louis Schefer)

Distinctive voice-overs are trademark in most of Wong’s films, these serve not only as the compass that navigates the story; they are more than that. The poetry of a person is revealed in these poignant moments of dialogue as the screen becomes the oblique confessional screen, as it separates it also lets us into a world that has been internalised, and different to the way HK people usually interact with each other - which is loudly, and sometimes forcefully. Where the external world is one of a busy cosmopolitan city, filled with detritus, debris, delusions; the internal world is desirous, pensive and inhabited by conscience, self-reflection, and prophecy. The slowing down of movement in some of these scenes heightens the internal emotional state for characters and audiences.

Wong helps us see these moments of reflection materially in his use of both the step-printing technique, and his distinctive slo-mo effect; the result is that of respectively striating and stretching time. In a city that is so fast paced (Hong Kong people prides themselves in being fast-walkers, dodging through the crowded streets without so much as brushing against another) time needs to slow down for us to experience the context that happens within those few seconds. In step-printing, this technique is achieved by the repetition and dropping of frames; for example, frames 1 to 12 are allowed to run consecutively, then frame 12 gets repeated for the next 12 frames to achieve a pause in the motion, and then frames 13 to 24 gets discarded and this process is repeated through a duration. What is experienced visually translates to a kind of slippage of the temporal. The memorable opening scene of Chungking Express uses such a technique. You can see Cop 223 running through the streets of Hong Kong, but his movements seem stilted as he stutters across the screen. The camera follows him as he chases his suspects, but whilst he is fully in focus, the people and surroundings all around him are a blur of colours and motion; the circus-like music that accompanies this conjures up a Baudrillardian universe of the hyper-real: time is disjointed, and loses its steady forward march into the future, and is instead fragmentary and not of the present.

|

| Step-printing – opening sequence to Chungking Express |

The slo-mo effect, on the other hand, stretches time. This is shown in one of the most well-known sequences of the same film, where Faye quietly observes Cop 663 drinking his black coffee after he refuses to take the envelope from Faye (containing the key to his flat from his ex-lover). The two are hardly moving, he is leaning against the counter at Midnight Express staring into space, and Fei is in turn staring at him; throngs of people speed pass them by in the sidelines; they are held in this dreamlike bubble - immobile and hardly taking notice of anything around them. Later, this effect is echoed in Fallen Angels (in the previously described b/w scene). This effect was achieved by shooting the scene at 12 frames per second with the main actors moving very very slowly, then played back through the projector at the normal speed of 24 frames per second. Time is dilated and stretched as though in a dreamic state; which is an internal state of the temporal.

|

| Slow-motion in Chungking Express captures the ineffable |

This disjunction of the temporal is an interior disjunction - the body in which we house our memories spill out onto the screen; even after we are dead. This is the magic of cinema, in that the dead speaks to us from beyond the grave, and the lens is one of divination which can look back into the past or cast an eye into the future.

The blossoming of nostalgia

It was no surprise that In the Mood for Love (2000) transitions from a contemporary HK to a HK of nostalgia, a temporally distant Hong Kong that is rich and textured, like its Cantonese namesake - 花樣年華 - ‘in full bloom’, or the ‘flower-like years’ of the early 60s, before the ‘66 riots and from the perspective of a child growing up in a Shanghainese household with an amah (Wong’s childhood perhaps). A childhood I know a little bit about, for I too, had a grandmother who rented a room to a couple in her apartment, we had an amah and a cook. As a child, my HK was filled with similar vignettes both in sentiment and sonically: the excitement of listening to the distinctive muted clacking of mahjong being played until the early hours of the morning; my uncle’s jazz trio; bossa nova sets played by said uncle and sung in Portuguese on Saturdays at my grandparents’ flat; whilst his mother (my other grandmother) listened to Cantonese opera on the wireless in the next room, playing mahjong; both smoking Kent cigarettes like there was no tomorrow. Then as the evening progressed, we would all saunter across to the flat next door (my great grandparents’ place) to have dinner. Memories of my mother and aunties dressed up beautifully, in handmade cheongsams with coiffured hair-dos and my dad and uncles dressed in tailored suits, hair slicked back just so, debonair and handsome.

|

| In the Mood for Love: the glory days of Hong Kong, depicted here by Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung |

The sumptuous In the Mood for Love in this latest viewing no longer told of a love story, or the story of a possible affair; but now I understand it to be a eulogy to the Hong Kong that once was. This experience for me is intensified by having re-watched Chungking Express and Fallen Angels just prior. For me, these two films of HK in the 90s speak to an impossibility of reconciling with a past that I’ve never had (a life in HK as an adult), in other words, this can only be a life you dream of on screen or in your darkest hour of sleep. But In the Mood for Love poses a returning to a childhood HK; a temporal destination where I am enamoured by familiar sensibilities that is not only a return to my mother tongue, but evokes flashes of recollection of my own childhood (not only Wong’s) now lit up on the screen.

The art of unnamed politics I: time-images

It’s difficult to understand what has happened for the Sydney Film Festival curator of Love & Neon(the Wong Kar Wai retrospective showing currently) to render the director’s name into simplified Chinese characters; and to use Zhang Yiyi’s image from 2046, rather than Maggie Cheung or Tony Leung’s images (famous HK actors) for their promotion banner. I feel that these choices have made Wong, a Hong Kong filmmaker into something else. As a native HK person who has migrated to Australia, I am unable to read (or recognise) the simplified character in his name, and found this change a disturbing one - it is though his identity has been effaced.

WKW does not politicise his films, or make explicit these sentiments; however, his message is like Mo’s secret in the dug-out recess in Angkor Wat - and is simply there; hidden in the milieu. Room 2046 where Mo’s character ‘makes a start’ of a martial arts serial, stating to Su that “starting something is the most difficult”. This double entendre hints at not only at the writing of the serial, but a reference to ‘how an affair starts’ within the narrative; but it is also posing that question of how to ‘start over’ again for Hong Kong following the handover in 1997; this is the tagline used by the exiled lovers from Happy Together ‘let’s start over again’. And we can do nothing else but start all over again. It’s as though Wong is consoling himself, as well as the cinema collective.

There is a yearning in the brooding faces and stance of Cheung and Leung in In the Mood for Love, repressing what might come to the surface; this internal burning, the intimate desire that is yet unknown to instead show a blank face of courtesy. Can one ever be able to read past the surface materiality of these filmic images? What is beneath the artistry and rich tableau of In the Mood for Love? Is it in the context of love or politics? Can the two be divided if it is the love of your motherland?

There’s a difference between making art and making a political statement through art. It seeps into the heart of the film, or its esprit. One stays with you, lingering, and haunting you, whilst the other provokes action. Deleuzean philosophy would say that the action-image is one that has a beginning and end, this trajectory or movement resolves itself in an outcome; whereas the time-image bifurcates rhizomatically. Submerged in the interiority of the narrative, there are glimpses of politics - body politics inscribed onto the materiality of film: the expiry date stamped on cans of food in Chungking Express can serve as both a warning - the expiry date on the tin of sardines means a certain fate for the drug runner if she fails to find the drug mules; and also one of parting - the tins of pineapples stamped with 1 May 1994 (May’s birthday) and the deadline in which if they are unable to reconcile, they will part. The rejection of expired tins by a homeless person poses a question: what happens if nobody wants an ‘expired’ Hong Kong once 1997 came around? Remembering that the word ‘to expire’ also explicitly means ‘to be no more’.

|

| The expiration date of a can of food as an analogy to the ‘expiration’ of a city-state |

Further contexts can be found in the milieu; in In the Mood for Love, the room ‘2046’ hints at 49 years of ‘no change’ (1997 + 49 years) and signals to the last year before the 50 year deadline of ‘one country, two systems’. The exploration of Wong’s roots as a Shanghainese ‘migrant’ into HK, replicated onscreen with Mrs Suen, and then her subsequent migration from HK to the US in the 60s. In hindsight, that was probably not a good choice for her; but Wong always looks through the lens of nostalgia rather than hindsight, as though history is already inscribed and so there is no need to state the obvious. It was a time of unrest with the ‘66 riots, the Vietnam war; where de Gaulle’s visit to Cambodia shown as a non-diegetic insert into the end of In the Mood for Love; to the lone figure of Mo in Angkor Wat. Why show the newsreel if there isn’t a point to make? Finally, at the end of the film, Wong’s end epitaph seem to be for those who have left Hong Kong as well as those who decided to remain: that they are always able to reach its shores temporally.

The art of unnamed politics II: sonic files

Is it possible to be in the same place, in the city of Hong Kong today, to still feel ‘close’ to the city of 1960s or mid 1990s Hong Kong? Just like in Fallen Angels, where the partner of the killer would frequent the bar the killer visits; in the hope of sitting at the same bar stool he sat at, just to be close to him even after he was already long gone. Or would it be that history is effaced, or readily forgotten, just as ‘blondie’ claims that she and the killer were once an item, but that he had forgotten her despite her change of appearance. Wouldn’t her essence still be the same and thus recognisable? Would the many corridors, MTR stations and gambling dens traversed by the killer and his partner somehow take us back to the lost city of Hong Kong? Maybe it is possible - through the incredible soundtrack by Frankie Chan and Roel A. Garcia (with a sampling of Massive Attack’s Karmacoma).The handsome cast of Leon Lai’s killer and Michelle Reis as his partner, epitomises the type of characters: cool, photogenic, idiosyncratic, ruthless but with a soft side, (made familiar by Tarantino on the international scene, and he was alternately inspired by Wong’s cinema); makes it easy for audience to relate to. At the end credit roll of its AGNSW screening last week, the film received a spontaneous round of applause and cheering from the crowd. Wong’s cinematic universe is rhizomatic; it bifurcates by conjuring up Deleuze’s crystalline ‘image’ sonically.

|

| Coolness epitomised: Michelle Reis (top) and Leon Lai in Fallen Angels |

Wong has always used a piece of music to inspire or to guide a create impulse that would then saturate the ambience of his films. And it is from this spark that the heartbeat of the film comes about. Take ‘Yumeji’s Theme’, a piece commissioned for the film that repeats itself throughout In the Mood for Love. Just to know that the Michael Calasso cello piece is called ‘Yumeji’s Theme’, would provide a glimpse of this other universe that is occupied by the Japanese film Yumeji (1991) directed by Seijun Suzuki of the real-life poet and artist in the 1920. This film reveals what Wong’s film does not; sex scenes, madness and the complete blurring of the dreamic and reality. The two films nonetheless are conjoined by name alone; Yumeji in Kanji is 夢二 which in Chinese literally translates as ‘Dream No. 2’ or the doubling of a dream; seeding the idea of a doubling of existence or a double life; perhaps even a dream life. What is the dream life of Mo and Su? Is In the Mood for Love the dream life for Wong’s Hong Kong?

|

| Inside Room 2046, In the Mood for Love |

The lyricism of his films is on the scale of the sonic as much as they are of the cinematic. Music has that immediacy of evoking a time, place, sentiment or a feeling. It can be very exacting in what it evokes and yet come to mean something completely different to each person. Wong’s films stitches together spaces and temporalities sonically, and through our collective memories.

And in the end, the love you take, is equal to the love you make

But what music evokes mostly, at least for me, is that feeling of elation, a kind of swoon that also comes with being in love. So, when leaving the cinema after seeing one of Wong’s films, I am in that enamoured state of being ever so slightly in love. Perhaps one of my most favourite scenes that captures this feeling, is the ending of Fallen Angels, where the killer’s partner voice over says: “As I was leaving I asked for a lift home; I haven’t been on a bike for ages, nor have I been so close to another person for a long time. Although I know this journey home isn’t very long, and very soon, I’ll have to get off. But in this moment, I feel such lovely warmth.” We see the killer’s partner in close up, her eyes half closed and head resting on He’s shoulders as they ride through the harbour tunnel in slow-motion to the Flying Pickets’ a cappella version of Yazoo’s ‘Only You’. And as they exit, the camera catches a curl of smoke from He’s cigarette as it drifts upwards, as the camera continues to tilt up we catch a glimpse the open pre-dawn sky of Hong Kong.

|

| Fallen Angels end sequence |

It is almost impossible to write about these films succinctly; but that they are the ‘must-sees’ of Wong’s films. I have written a much longer piece that is posted on my blog #nightfirehorse which I’ll post a separate link to shortly.

Whilst Wong is known for his poetics; his cinema is populated with good-looking, brooding characters, Chungking Express and Fallen Angels have a lightness to them. These films explore the idea of love and distance; where in a densely populated and over-crowded city, the people of Hong Kong have a shrink-wrapped personal space - what is the possibility of finding love?

The films are intertwined, characters like the one played by the very handsome Japanese-born, Taiwanese star Takeshi Kaneshiro, traverse Wong’s filmic universe metamorphosing from one film into the other; as does his ‘counterpart’ played by Brigitte Lin (another big Taiwanese star) dressed in heels, a trenchcoat, sunnies and a blonde wig - is reminiscent of Cassavetes heroine in Gloria - and later in Fallen Angels, another woman with a similar styled haircut that’s dyed blonde seduces the killer; and yet another woman is in search of ‘blondie’ - the woman who stole her lover.

Leon Lai’s killer and Michelle Reis as his partner in Fallen Angels are the epitome of cool, as punctuated by the charismatic soundtrack by Frankie Chan and Roel A. Garcia. Whilst Faye Wong and Tony Leung’s story in second half of Chungking Express is so spontaneous that their on-screen chemistry is palpable, and they tell their alluring little love story so very lightly.

Most of the actors were only given a page of script on the morning of the shoot, and the rest improvised throughout the day; with Chungking Express only taking 23 days to shoot (the part with Tony Leung only 10 days). Christopher Doyle’s now legendary cinematography is as haphazard as it is poetic and fresh - imagine this, he lent his tiny flat in Central for the shoot for Chungking Express (Cop 663’s apartment), his life literally turned upside down for those couple of weeks.

Although the cinematic narrative is fragmented - seen through slits, or doorways, with handheld ‘gonzo’ camera work; Doyle also captured many of the characters in extreme close-ups - the Deleuzean take is that this is an “affection-image...where the close-up is the face”. The landscape of the face is always one of the temporal, shown in slow-motion it has the ability to transcend the story it’s set against, to create one of its own.

In the Mood for Love on the other hand, is a return to a Hong Kong of the 60s - nostalgic, sumptuously shot, and richly textured. The mood of this film makes you literally fall in love with the actors: Maggie Cheung’s cheongsams accentuated her long swan-like neck and graceful figure, Tony Leung in his dark suits and slicked back hair epitomises an era when dressing up was the norm. An era that can only now come to signify a Hong Kong as a memory-image, and temporally distilled in Wong’s imagining of it in this time; and no long our Hong Kong of the present.

Love & Neon: The Cinema of Wong Kar Wai is running until the 18th February#dendynewtownand #AGNSW

#loveandneon is part of the #sydneyfilmfestival

This essay was first published on Janice Tong's blog Nighthorse.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.