Wake in Fright (Ted Kotcheff, 1971, Australia/USA) is the subject of a forthcoming book by writer and

filmmaker Peter Galvin. Peter is interviewed here by critic, author and former Sydney Film Festival Director Lynden Barber*

Based on Kenneth

Cook’s novel of the same name, first published in 1961, it’s the story of a

young school teacher, John Grant (Gary Bond) who becomes stranded in an outback

city called Bundanyabba (the Yabba) on his way home to Sydney where he plans to

spend Christmas holidays.

What follows is a

lost weekend of boozing, cruelty, lust and violence. The plot provides John

with a series of ‘guides’ – Yabba locals - each of whom challenge his bitter

snobbery of the Outback while tapping his own buried desires…

These include menacing

local cop Jock (Chips Rafferty), and an intellectual alcoholic bohemian called

The Doc (Donald Pleasence). The cast includes Jack Thompson (in his first

feature) and Peter Whittle as beery ‘Roo shooters, John Meillon and Sylvia Kay.

|

| Jack Thompson made his feature film debut in Wake in Fright and credits Kotcheff as a particularly fine 'actor's director'. |

By the end of the

70s it was difficult to see. By the 90s its

original materials were thought lost.

The film’s editor, now esteemed producer Tony

Buckley (Caddie, Bliss), spent years in the search before he found Wake in Fright’s original neg and sound

in order for it to be restored. It was

re-issued in 2009 and since then has screened in hard top theatres and been released

on home video formats in Australia, USA, Japan and the UK (amongst others).

Peter Galvin, an

occasional filmmaker, screen studies teacher and long-term writer on film has

spent years researching and writing the book which not only details the making of

the movie, and the life and work of its key players but also explores the

origins of Ken Cook’s novel on which the film is based.

Still, he is

quick to correct any assumption that this is to be a volume for fans only or

the kind of publication that will attract only the most dedicated of cineastes.

|

| Promotional pic for the book designed and created by Peter Galvin. |

Instead he hopes

it will appeal to a mainstream audience interested in biography and Australia’s

pop culture of the 1960s.

“There’s material

here that you would expect,” he says, “the influence of the Cultural Cringe in

culture and politics, the mechanics of TV and film as played out in boardrooms

and nightclubs, the film culture scene in Sydney and Melbourne, the behind the

scenes trade-offs in business where ego is a casualty in getting a project to

‘greenlight’…but there’s also lots of other intriguing stuff that’s part of a

rich historical mosaic that throws the story of the making of the film and its

impact into relief: Sydney’s illegal gambling dens of the 60s and the history

of Two-up; Aussie slang and accents; the compelling reach of the RSL in every

corner of the culture here in the 60s; the role of the kangaroo as pop art

symbol; the dominant masculinity confronting feminism and gay lib; a portrait

of Broken Hill, a strange city then, run by a Union (it was the key inspiration

for the book and the main location for the film); live TV drama in Canada and

the UK…”

INTERVIEW

Why is Wake in

Fright important?

Well, I’m not

writing a book that sets out to argue that it is. I mean for me it’s a given. I

don’t want people to think the book is in the ‘this is a great work and why’

genre of film criticism or one those lengthy testimonials with lots of great

filmmaker minutiae.

(I have to say I’m not snob about either of

these angles on this kind of subject.) That said, I do think the film is

important. There’s

an assumption – backed up by received history – that the film was a watershed,

a focus of optimism arriving right at the threshold of a new decade. It was

understood as a rallying point for a nascent film industry and it was accorded

a great deal of respect by filmmakers and many critics on first release in

1971. Its reputation has only grown since and I would argue that it is indeed a

classic. Though such labels are always up for grabs, no?

Trouble is, Wake in Fright is not a film that has ever received a great deal of

critical attention in the sphere of scholarship/the academy/or middle brow

critics, so that familiar swing we know – ‘freshly discovered classic /

consensus / revision / new estimation’ - has never happened to it on any kind

of scale.

Why is that since the movie’s critical reputation is

so strong?

Well, I’m not in

the space but even as a casual professional reader there is a lot of stuff out

there begging for the attention of researchers, academics etc, and frankly Ted

Kotcheff is not now, nor was he ever positioned as an auteur by anyone. Which is, to be blunt, the

lightning rod for special scrutiny amongst academic critics of a certain kind –

and those who publish their work in peer reviewed journals and books. He was

not even the first choice for the project, he was a hired gun…though once he

did take it on he really made it his own…which created all sorts of issues.

Really? What sort of thing are you talking about

here?

You’ll have to

read the book.

How did the book start?

That’s a long

story. Even the short version is a long story.

Try.

OK. By this stage

– it’s been, like most books, I figure, a lengthy gestation, many years in

fact. It’s taken on the aspect of an obsession.

|

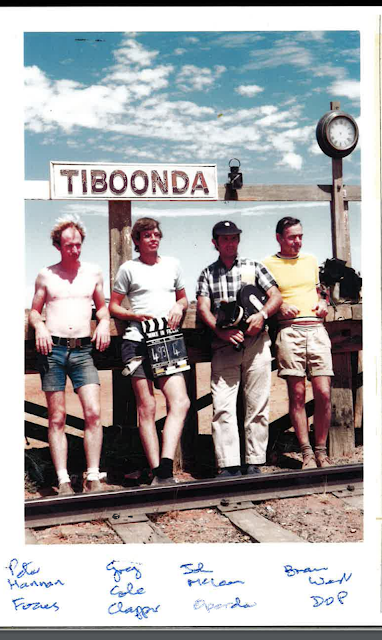

| Johnny McLean (with camera) and crewmates on location in the outback near Broken Hill in Feb. 1970. From JMs private collection |

I studied

Australian Cinema at UTS - this was the late 80s - and that’s when I really began

to look at the films of the Revival as

cinema in a fresh way. I started teaching Australian cinema in the late 90s.

I have always

leant heavily toward to an auteurist

sensibility. I think that it is true that even the most banal sensibility can’t

hide behind a camera. One needs to heavily qualify it. But then something like Bazza McKenzie leads one into a discussion

of the Sydney Push, Ubu Films, the Satire boom of the 60s, the Melbourne Eltham

scene, the Film Societies and the traditions of a certain kind of Aussie comedy,

Brit-Aussie competitiveness and how those attitudes and sensibilities are

formed and collide…

Does A Long

Way from Anywhere touch on these feelings?

Yes. It is a

narrative which is very much about the forces within the Australian experience

of the late 60s that played a role in influencing the Revival. I remember an

old friend, a producer – he left the film industry a long time ago – saying to

me that ‘Australia, in the late 60s invented a film industry’. That thought

really resonated – even if on close scrutiny it’s a leaky premise. But still

the idea that ‘necessity is the mother of invention’ does have some merit in this history. I mean it is true that there was a powerful feeling in

the 50s and 60s here that a cinema of our own is something we needed! This was exactly how it was

written about and discussed.

Is this your first book?

Yes. It actually

came out of an abandoned project. The model for the abandoned book was Otto

Friedrich’s City of Nets. My book was

a social and cultural history /group biography of the Australian Feature Film

Revival. But I was too young, the scope of the book too big, and I discovered

it was very hard to write about people who are still living.

What happened?

I moved on to

more teaching and getting involved in screenwriting – I sold a script and took

on some writing commissions and made short films…

|

| Camera crew poses for a snap at the Tiboonda set near Broken Hill. Feb 1970. From JMs collection. |

When did you see it?

On TV. Bill

Collins Picture Show. Late night. I was still at school. It completely blew

away. My parents come from the bush – though not the Outback. I recognised the

attitudes, the vernacular, even the way people moved and all those silences, the awkwardness strangers take on

when faced with forced intimacy and the emotional claustrophobia that comes

from the pressure of performing in

order to fit into a mood in a social situation – and the reckless choices that

can emerge when confronted with opportunities that offer a chance to escape

that feeling! I can articulate my feelings

now…then I just knew it said what I felt.

Now I know what I was experiencing was a kind of authenticity. And as style, I

loved it.

Today it’s thought

of as a sort of gothic mood piece. But in the way Kotcheff moved the camera and

Tony Buckley’s editing and the choice to demonstrate drama physically and in cinematic terms – there was a kinship with that

robust kind of movie making which in the 60s was thought of as the tropes of

action cinema. I’m thinking of Frankenheimer. In researching the film, I

discovered indeed the producers approached action directors before Kotcheff

took the job!

But most

importantly it was the first time I ever experienced an immediate shock of

recognition on every level. I recognised it was both stylised and true. And the acting was really very

good.

|

| Belguim poster used in the films original rel. 1971-72. |

The search for

the film and its restoration.

As I mentioned

Tony Buckley was editor on the film. Every so often over many years he would

drop anecdotes about its making…Tony has the native instincts of the historian.

And he carefully detailed the story of the search for the film in his memoir Behind a Velvet Light Trap – it lasted

years.

So, I was very

conscious – as I think the most casual film fan here was – of the search for Wake in Fright – mostly because Tony was

very good at publicising it. Once the restoration was underway I thought it

might make an interesting oral history and since the NFSA were central to the

process I felt they might be interested in a book.

When was this?

2008. Tony had

tipped me that by early 2009 the restoration would be ready for release.

I was intrigued by the fact that there was very

little written about the novel and very little about Ken Cook, the novel’s

author. He’s a tremendous character: a genuine eccentric, an under-rated writer and

terribly adventurous and restless. So right from the start I felt that the

story of the film began with the story of Wake

of Fright the novel.

By April/May 2009

I had interviewed almost all of the surviving cast and crew in addition to

friends and relatives of Ken Cook. It was a firm basis for a monograph and I

raised the idea with the NFSA.

What happened?

Nothing.

They weren’t interested?

Definitely not in

a book, by me.

What did you do?

I pitched what I

had to SBS Film (now SBS Movies) as a three-part monograph, which looking back

was more than a little pretentious – but they took it, bless ‘em, thanks to the

SBS Film editor Fiona Williams. Meanwhile, the NFSA had their own monograph

planned through Currency Press, the Australian Screen Classics series edited by

Jane Mills.

A writer was

commissioned but the planned book never materialised. It’s never been made

clear – at least in public – the precise reason why this project was not

delivered (of course there is no call for it to be made public!). In the end

Tina Kaufman wrote a monograph for the CP ASC series - an elegant blend of

memoir and anecdotal history. But the NFSA came back to me before that!

Why?

They needed a

media kit. So, I was commissioned to do it. They offered a good cash deal and

since I was financing a short film I took it. Part of the deal was that I

wouldn’t claim an authorship credit. That was my idea.

Because of the SBS thing?

Yes.

You returned to the project about two years ago, why?

Part happenstance,

part design, part necessity. I had always wanted to do a hard copy version of

what I ended up calling A Long Way from

Anywhere. The title is a nod to Broken Hill, which is the model for the

Yabba in the book…it’s a bit of a saying Outback folk have used for decades

about remote locations but it’s often directly linked to the Hill…but I also

like the way it suggests that cultural isolation we identify with as part of the

Australian experience of the 60s.

I wrote the text

of the online version very fast. There’s a swagger to it I don’t like. The

balance is not right between commentary, anecdote, analysis. It’s not entirely

fair to some of the real-life players in that their contribution isn’t accorded

the space it should. Its principal virtue is that it featured an enormous

amount of fresh material not found elsewhere, and some very funny and

insightful anecdotes.

The actual moment

when I pressed the ‘start’ on the book was Winter, 2016. I was having dinner

with Tony Buckley, who has been a friend for decades and he suggested I take

another look at the material for a hard copy version…two months later I was

jobless – a contract had ended – I was at a loose end and I thought this was

good timing! I was encouraged to move forward by a few close friends even though

I knew it would be difficult since most of the principals are dead.

Did you go in with a set of ideas – a sort of thesis

you wanted to prove?

No. But when

planning the book, I knew I had no desire to add to the large library of books

on Australian cinema that are scholarly expressions on certain well-trodden

themes (and again those books are invaluable!). Besides, I don’t

think I am at all qualified to write that sort of thing (a piece of

self-assessment I am certain will meet with enthusiastic approval from the

academics I know!!)

Instead, I wanted to write a book of popular history and do it as a narrative. No one has ever a written a narrative history on an aspect of Australian cinema where biography is equal to other significant factors of historiography. There’s been memoirs, and things like Ina Betrand’s Australian Cinema book, and interview books and TV shows.

Instead, I wanted to write a book of popular history and do it as a narrative. No one has ever a written a narrative history on an aspect of Australian cinema where biography is equal to other significant factors of historiography. There’s been memoirs, and things like Ina Betrand’s Australian Cinema book, and interview books and TV shows.

A Long Way from Anywhere is really a book that attempts to capture the moment of Wake in Fright – that point from the early 60s right through to the

dawn of the new decade. The changes in the Australian experience were

extraordinary. Which is why it’s a social and cultural history. The aim is to

create as vivid a portrait as possible of the filmmaking and showbiz subculture

here c.1961-1971 through a select cast of real-life characters all of whom had

direct or indirect impact on the making of Wake

in Fright and the Australian Feature Film Revival here. So, this part of

the book is very conventional narrative history. I’m after a blend of

biography, film criticism, film history, social and cultural history all told

in a very intimate way but built on a solid foundation of original research

with special attention to the principles of sound scholarship.

Talk about the research?

Well, that’s been

very enriching and very exciting. I can boast I’ve uncovered a great deal –

much more than I thought I would. But it has been tremendously difficult in

that I don’t have a budget and I am in Sydney and so much of the primary

sources are to be found in the UK, the USA, Canada, France, Poland and Norway

and here in Broken Hill, and at the National Library.

What was your research process for the O/S component?

I wrote a lot of

emails and begged strangers for help. Happily, they were kind, professional,

efficient, forthcoming and in all instances provided me with more than I asked

for and pointed me in the right direction whenever I needed it. When people

heard about the book they were very enthusiastic. I’ve dealt with libraries and

archives in England, France, Norway, Poland and the USA.

These were documents and so forth?

Yes! Manuscripts,

professional miscellany, reviews of the film, stills, business archives,

private letters, newsreels, TV archives... I’ve also tracked down extras, cast

members with tiny roles, in addition to doing much biographical work on the cast

and crew and at NLT and AJAX Films - AJAX provided film services to the production– talking

to friends, sourcing private memorabilia. Most of these people I am talking

about died a long time ago including Gary Bond who played the lead in the film.

Is a lot of this research unique to the project?

Certainly! Early

on I received the co-operation of the Wake

in Fright Trust. The Trust is the copyright holder. With their support and

permission, and with the tremendous assistance of the Trust’s lawyer Raena

Lea-Shannon I was able to gain access to the entire archive of NLT which is at

the Mitchell Library in Sydney. Very few people have seen it and fewer still

have seen it all. I spent many months perusing every single bit of it! But I

should point out that the pioneer for the TV part of my story is Albert Moran.

His published stuff on NLT, though there isn’t much of it, is great.

What I have you discovered?

You’ll have to

read the book. But I set out to answer certain questions. Right now, they have

answers on the public record which in almost all instances are garbled, or flat

out wrong.

For instance?

Well, the

identity of the film as an Australian film. This is not so cut and dried. But I

remember just before the film was relaunched in its reissue in Australia at the

Sydney Film Festival in June 2009. It was without question one of the hot

tickets of the festival and I asked a professional colleague, a local, someone

who was a producer, who was almost but not quite a contemporary of the film

whether they were planning to go to the screening. They were not. And their

reply was disdainful: “They’re not trying to say that’s an Australian film now, are they?”

Now on the

surface that attitude as wrong as it is, is easy to understand. Kotcheff is

Canadian, the nominal producer presented himself as English (he wasn’t), the

screenwriter was English/Jamaican, the DOP Brian West was a veteran of the

English studios. The money was 50/50. Half of it raised here by NLT and the

other half presented to NLT by their American partner Group W, a Westinghouse

subsidiary.

Still, once one

understands all these roles in business terms and understands how the film got

prepared to the point of production c.1968 – then terms of identity need to be

reassessed. Or to put it another way NLT the Australian producers were

responsible for the film. They found it, developed it, packaged it, cast it, and

searched out and found an overseas partner in order to make it…because they and

they alone made the key decision: to make

the movie! Aside from the cash, which is not insignificant, one could

describe Group W’s practical and aesthetic contribution to the film, as, and

I’m being kind here…negligible.

Who was NLT?

The founders were

Jack Neary, entrepreneur, promoter and talent agent, Bobby Limb, a star in the

60s on TV big enough to rival Graham Kennedy, and Les Tinker, a businessman,

who died soon after NLT was formed in the early 60s.

The deal NLT made

with Group W presented certain hurdles all justified by an understanding of the

market and also those points that traditionally are ways to exert executive will

over the creative process: Group W demanded director approval/script approval

and a star part that would be acceptable in America. They reserved the right to

make changes as well as demanding NLT be entirely responsible for the making of

the film! They also wanted a package: two films a year for five years and NLT

had a number of properties Squeeze a

Flower, The Long Shadow and Wake in

Fright. Group W got their deal and NLT got their money. ***

As to Wake in Fright the material is of course

Australian – indeed Australian-ness

of a kind seems crucial to an understanding of its content.

There’s no

question that in a certain significant way Wake

in Fright is an outsider’s view of Australia. But then Ken Cook felt like

an Outsider, in that place, the Outback, when he first went to Broken Hill in

the early 50s and that’s the entire basis of the story! Still, if one takes

Kotcheff as the author of the film – that’s a critical convention that deserves

to be respected - and highly qualified. But it’s interesting Wake in Fright arrived during a wave of

‘internationalist’ productions. I’m thinking of Blow Up, Last Tango in Paris, to take two prestige pictures. The

national identity of these pictures is confused with their production identity

and the identity of the auteur which overwhelms everything! But there are

countless B movies where the money might be American and British or German or

French, the crew from all over and the film shot in say, Spain whose

appropriateness to the story is less significant to its attractions to the

production as a cheap place to shoot!

This was Group

W’s preferred model of operation, incidentally. They were part of 30 movies and

none of them made any money but as tax breaks they were blockbusters! Of course,

the issue of the identity of Wake in

Fright is made sensitive in the context of 1971. The point being that local

pros in film wanted something they could call their own without question. I was only reading the other day a

conference paper delivered by Tom O’Regan (from the early 80s) where he very

eloquently summarised the push for a Revival in the 50s and 60s as part of a

surge of new nationalism amongst intellectuals/artists – and they were quite

dismissive of the ‘foreign film made here’ picture and it was not to be confused

with the indigenous thing. But those same writer/critics O’Regan was talking

about: Colin Bennett, Sylvia Lawson, Mike Thornhill to name three prominent

figures at the time – they really got behind Wake in Fright and framed it as an Australian film – if directed by

a Canadian! All that aside, I discovered something interesting. Amongst below

the line crew at the time WiF was

thought of as Australian made, no question!

Do you see the book as an opportunity to alter

peoples view of how the Revival evolved?

Absolutely. If

the book, God help me, has some merit it will be trying to give a fresh

portrait of what happened in the world of film here between 1968-1972. I mean

the odds were stacked against Wake in

Fright from the start.

How do you mean?

Well, a lot of

properties start off as ‘orphans’ and if they can’t find a home soon after they

get to the marketplace they are branded as ‘difficult’. That’s code for

un-makable…sometimes the block has something to do with the content, or the

star part is unattractive, or the production demands make it costly on the

expected returns…there’s countless reasonable reasons and even more plausible

excuses not to make a movie than can

ever be reasons to make a movie and

the Wake in Fright property fell foul

to these realities immediately.

I’ll correct one

popular assumption about the films evolution from book to screenplay to movie

in answering this. Joseph Losey never

had the rights to Wake in Fright.

Dirk Bogarde and his long time companion and business partner Tony Forwood set

up their own production co. in the mid-50s. After Bogarde left Rank he wanted

to smash his matinee idol image which he made fun-of and loathed. He searched

for vehicles to star in and produce and bought the movie rights to Wake in Fright soon after the book was

published in London in 1961. He had visited Australia in the war years. I think

he recognised there was an opportunity to explore some stuff in the piece about

role play in a hermetically sealed environment and submerged murky sexual

feelings…things that we know interested him and themes he would return to. Of

course, he made that movie The Servant,

didn’t he?

What happened?

He hired Evan Jones (5) to

write the screenplay and attached Losey to it as director. He even

paid Losey to commit his involvement to it. It was announced. It fell over.

From what I understand the market felt the film’s commercial prospects

negligible and the money was never there – I mean I really think that they were

never that serious about it since they never came out here to investigate the

possibilities and for Bogarde and co. it was just another property amongst

many.

A few years later

Morris West bought it and the Jones script for a new production venture he has

set up in Rome with Maurizio Lodi Fe (Bread and Chocolate). West actually wrote an uncredited pass on the

script and this version was thought to be lost. But I found it. West, like Bogarde and co. struggled with

it. I think both these groups didn’t even get to the point where they had found

solutions to the film’s production challenges – beyond throwing money at them

and I think that’s why they foundered.

How did it come to NLT?

You’ll have to read the book. But they saw no

reason to bring in another writer since Jones’ work was excellent, Cook had

been close to its development from the start and Cook had ties inside NLT…but

NLT paid for a re-draft. Still, there’s a lot of drama in the story precisely

because the market and indeed professional filmmakers just couldn’t put Wake in Fright together with NLT. It

made no sense. They made variety shows. They made kids shows. They did TV

variety specials. They guided the careers of a huge roster of talent through

their agency interest…but their management team had absolutely no experience in

either the business of films nor the making of films and the showbiz scene here

couldn’t believe that as the old studios in the USA were being disrupted by new

models and global audiences for movies were shrinking this small but prosperous

TV and talent co. in Sydney wanted to get

into the movies! I mean the players here thought they were insane.

Because there was no film industry?

Because there was

no film industry.

What’s the explanation?

Well, the

personalities involved, and their network played a significant role.

Jack Neary was

widely admired for his decency, and his eye for fostering talent…but Neary was

considered ‘old-fashioned’ and there was suspicion that the wrong co. got hold

of a great property. Still, there was a belief that no matter what - NLT would

see this through.

Bill Harmon is

crucial to the story. He was the driving force behind Wake in Fright at NLT, the executive in charge of production. He was

an outsider. An American, Jewish (NLT was full of Catholics), very showbiz,

Broadway, a veteran of live TV on US network, who had worked for some

hard-cases like Jimmy Durante who knew how to take a hit from talent and keep

cool. Neary had hired Harmon to ride shot gun on production at NLT. After that

NLT had a reputation as ‘cowboys’.

But what I

discovered in the NLT archive was that very early on in the life of NLT Harmon

convinced the execs to spend time and resources on ‘schooling’ themselves in

the minutiae of movie making. They didn’t rush into it. They took years to get

to the point where they felt confident to move forward. Their ambition had credibility. But the trouble was

they had no track record and the perception that they were maverick cowboys

became impossible to displace…until people saw the film. That changed

everybody’s mind. But by then NLT were coughing blood.

Why?

You’ll have to

read the book.

Visit

it and like the A Long Way from Anywhere

FB page

https://www.facebook.com/alongwayfromanywherethestoryofwakeinfright/

1. Lynden Barber is a Sydney-based film teacher and journalist

and a former artistic director of the Sydney Film Festival.

2. Some of the titles Galvin is thinking of include Newsfront (Phil Noyce, 1978) Caddie (Don Crombie, 1976), The Devil’s Playground (Fred Schepisi,

1976), The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (Fred

Schepisi, 1978), Alvin Purple (Tim

Burstall, 1972) Sunday Too Far Away

(Ken Hannam, 1975), Picnic at Hanging

Rock (Peter Weir, 1975), The Last

Wave (Peter Weir, 1977) and Stone

(Sandy Harbutt, 1974).

3. Squeeze a Flower was rel. in early 1970 to great indifference. It was

directed by American Marc Daniels. The

Long Shadow based on the novel by Jon Cleary was never made.

4. According to Australian contemporaries these following films

were in the ‘foreign films made here’ category: Kangaroo (Lewis Milestone, 1952, USA), Summer of the Seventeenth Doll (Leslie Norman, 1959, USA|Aust.|UK),

On the Beach (Stanley Kramer, 1959,

USA), The Sundowners (Fred Zinnemann, 1960, USA|UK|Aust.) and all the Ealing

Films produced here including The

Overlanders (Harry Watt, 1946, UK|Aust), Bitter Springs (Ralph Smart, 1950, UK|Aust.), and The Shiralee (Leslie Norman, 1957, UK).

5. Evan Jones had worked with dir. Losey on Eva rel. in 1962. Another e.g. of an

‘internationalist’ production, incidentally.

A Long Way from Anywhere The Story of

Wake in Fright An Australian Classic will be published in 2019.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.