Thursday, 30 December 2021

Streaming - David Hare welcomes a new edition of THE FOUNTAINHEAD (King Vidor, USA, 1949)

Tuesday, 28 December 2021

On Criterion Blu-ray in a 4K restoration - John Baxter recommends TAMPOPO (Juzo Itami, Japan, 1985)

From Ratatouille to The Hundred Foot Journey and Chef, recent cinema has given us plenty of films in which characters are motivated by the pursuit of culinary excellence. None, however, rivals Jûzô Itami’s 1985 “noodle western” Tampopo, now available in a new 4K restoration with superior English subtitles. Noboko Miyamata

Western food tends to a deracinated norm. Pizza, curry, sushi and tacos transcend frontiers. Britain’s most popular dish is Chicken Tikka Marsala. When France’s first McDonald’s franchisee dared to tinker with the beef patty recipe and the dimensions of his frites,the home office in Chicago shut him down. Whether in Ankara or Alice Springs, a Big Mac must remain a Big Mac.

Anyone, however, who has eaten in Japan knows that such rules apply less there. Pizza and hamburgers are still available, but the range of regional delicacies and the variety among even such quotidian materials as pickles and pasta is matched by an attention to freshness and quality in fruits, meats and seafood that can verge on the fanatical. Where else are apples and pears chosen predominantly for appearance and displayed in individual styrofoam jackets to guard against bruising?

The same discrimination applies to the simplest of dishes, in particular the soft rice noodles in a meat-based broth, garnished with pork, shrimp and vegetables, known as ramen.

The contents of their trailer/tanker – milk – may put Goro and Gun (Tsutomo Yamazaki and Ken Watanabe) relatively low in the hierarchy of long-distance truckers but they share the professional interest in good roadside food. Their hopes for a new ramen place run by the widowed Tampopo – “dandelion” in Japanese – (Noboko Miyamata) are dashed, however. The barflies who clutter her establishment merely exacerbate its more basic problems; the tepid water in which she cooks the noodles, the lack of imagination evident in her broth, and a lacklustre range of garnishes.

Gun is ready to push off in search of a better meal but Goro, older, and exhibiting a courtesy and sympathy for the weak and afflicted worthy of John Wayne, bows to her wishes that he stay and undertake her education in the art of ramen. He also, no less in the spirit of the Duke and Howard Hawks, defies the barflies in a one-sided brawl that wins the widow’s heart.

After that, the resemblances, perceived by some reviewers, to Rio Bravo and Shane are less evident. It’s closer to those episodic films à sketches – Les Sept Peches Capitaux, Boccaccio ’70, L’Amour à Vingt Ans - that were an art-house staple of the sixties.

As Goro guides Tampopo through the intricacies of preparing and serving ramen, Itami cuts away to vignettes illustrating Japan’s complex relationship with food. An aged guru (Yoshi Kato) demonstrates to Gun his almost Zen manner of consuming ramen; how one should delay eating until one has appreciated the sheen of the soup, and offered a silent prayer of thanks to the ingredients for their sacrifice.

Elsewhere, an instructrice in foreign manners explains to debutants how to eat spaghetti Western style - neatly and in silence - until a nearby eater wolfing his noodles in the traditional manner sets off the students in a frenzy of slurping.

Kôji Yakusho, Fukumi Karoda...and raw egg

A group of vignettes features Kôji Yakusho as a suave white-suited yakuza and Fukumi Karoda as his adoring lover. Together, they indulge in some gloriously perverse sexual games, including placing scrabbling live shrimp under a glass bowl on her bare abdomen, and slipping a raw egg yolk from his mouth to hers and back again until it bursts orgasmically and drools from her lips.

The most sexually charged of these scenes takes place at a seaside village where Yakusho encounters some young girl divers. From one of them (Yoriko Doguchi) he buys an oyster. When, as he tries to eat it, the shell cuts his lip, she detaches the meat and invites him to eat it from her palm. Just before he does so, a drop of blood falls onto the glistening, vaginal flesh. The girl blushes and lowers her eyes, aware of a sexual dimension she is still too innocent to name.

Yakusho is also given the film’s final scene. Dying violently after a shoot-out, he fantasises to Karoda about eating sausages made from the intestines of wild boar that have gorged on sweet potatoes. “We will eat them together,” she murmurs as he expires.

Itami’s few films as director share a vision of modern Japan as a nation where samurai concepts of bushido coexist uneasily with the supermarket and shinkansen. It was a conflict of which he became a victim. After Tampopo, he was attacked and his face slashed by yakuza arguably angered by Yakusho’s character in the film. In 1997, his body was found on the street in front of his Tokyo office. It’s alleged that yakuza forced him to write a spurious suicide note, then threw him off the roof.

A good subtitled copy of Tampopo in two parts is also streamed HERE

Sunday, 26 December 2021

Defending Cinephilia 2021 - First instalment of the annual series - The editor offers his thoughts

So… a delayed start to this series where cinephiles are asked to offer five highlights that made their year.. but contributions now called for and previous contributors will be contacted

|

| Mary Harald, Tih-Minh |

Tih-Minh (and Judex) on Blu-ray

David Hare leapt all over this and you can read his thoughts IF YOU CLICK HERE but what has to be recognised is the fact the French taxpayer paid hundreds of thousands of Euros to get these films restored and returned to an adoring public. A couple of years ago French producers had access to an annual fund of some €30 million to have their back catalogues restored. Needless to say Gaumont and Pathe would have been the major beneficiaries. But when you have Feuillade in your backlist you have both an awesome responsibility, a huge cost and a massive opportunity. The French lab outpost of Bologna’s L’immagine ritrovato has done the company proud with these two films, now released on Blu-ray. David Hare didn’t mention the extraordinary music score by Julien Boury nor the very subtle incorporation of some sound effects – bird song, the sea, pistol shots.

As a matter of interest, it was reported that Emmanuel Macron’s government has slashed the funding for this program down to €3 million or thereabouts per annum. Nevertheless the most recent list on the CNC site, which you can find IF YOU CLICK HERE means we can look forward to more Feuillade (Vendemiaire) as well as more restorations of Gance, Truffaut, Carax, Becker, Mocky, Capellani, Franju and Doillon among a host of others from every era of French cinema.

Tih-Minh has largely existed in a terrible copy on YouTube. It has French and Dutch intertitles. I tried to watch this version on a couple of occasions but gave up early. You can see what I mean IF YOU CLICK HERE.

Ever since Tom Milne wrote about a Feuillade season at the NFT, using 35mm nitrate prints from the Cinémathèque Française, Tih-Minh always had a reputation that placed it in the same Pantheon as Fantomas, Les Vampires and Judex. Now we know.

OK.ru

You can think of it as the 21stcentury equivalent of the public lending library. That’s the most benign view. Needless to say many producers and their heirs and successors going back over a century think of them as thieves, and no doubt despise the Russian authorities who turn a blind eye to permit blatant free exploitation of someone else’s intellectual property. OK.ru has become the go to site for enthusiastic cinephiles to upload their treasured collections for all to see. No one gets paid to upload a movie, no one gets charged to watch whatever they find in whatever condition they find it. And its all there in plain sight not some dark backchannel where whatever is the latest has been purloined and uploaded mostly to cause grief. Some of the OK.ru users are utterly dedicated to the task of bringing the cinema’s history out of its closets and archives. By my count, someone called FleurRinna Guta has uploaded some 8000 films, all neatly categorised by star name, genre, period and nationality. A labour of cinephile love.

|

| Cecil Holmes |

Cecil Holmes and Three in One

The conventional wisdom about Cecil Holmes and his film Three in One is that the first two stories of the trilogy "Joe Wilson’s Mates” and “The Load of Wood” were very good and the third “The City” written by Ralph Petersen, was a clumsy and rather artless afterthought. Wrong. The screening of Three in One at Cinema Reborn in April, on a 35mm print from the NFSA that had hardly ever been through a projector, caused many to sit up straight and do a major re-assessment. The first story with its interpolations of some cod songs by The Bushwhackers goes on far too long. The second with Leonard Teale and Jock Levy is a small masterpiece. Petersen’s story captures the zeitgeist of the day superbly.

The screening reminded me, if nobody else, that the AFI never honoured Cecil Holmes with the Raymond Longford Award, an oversight I shall not dwell on except to refer you to the list of winners. Many of them are exceptionally worthy but..

|

| Moly Reynolds and David Gulpilil |

My Name is Gulpilil

Moll Reynolds tribute to Gulpilil barely arrived before the great man passed on. A magnificent tribute and a reminder of an extraordinary life and unique career. The sequences featuring an unknown to me one man show that Gulpilil performed should surely be a priority for NFSA preservation, restoration and circulation.

|

| Jed Mercurio |

Jed Mercurio

Nobody does TV like Jed Mercurio. Ten years of Line of Duty is one thing. Throw in Bodyguard and an EP job on Bloodlands in just the last couple of years and you get quite some kind of prolific ability to keep millions enthralled.

Saturday, 25 December 2021

"Everybody has to do the work they feel they have to do" - Part Two of Tom Ryan’s conversation with Ken Loach about the British cinema and working in "an absolutely collective enterprise".

If there’s one thing that distinguishes your work from that of your contemporaries in Britain at the moment – I’m talking about films like Billy Elliot (2000) and Bend It Like Beckham (2002) – it’s that they deal with the exceptions while, as I see it, you deal with the rule.

Well, yes. I hadn’t thought of that, but it’s probably true.

What do you think about those other films?

Oh, well. It’s hard enough to make them without somebody coming along and knocking them really. I mean everybody has to do the work they feel they have to do. I mean, if you go so heavily for comedy or sentiment or whatever, I think inevitably you coarsen the subtleties of the way things are.

You know, the result is you steamroll around the nuances of behaviour and the subtleties of relationships that reveal a lot because you’re driving hard for the comedy and you have to play it in a certain way. So I just find them less interesting. I don’t want to knock them because it’s tough enough to make them anyway.

Can I ask you another way? If you were making a film like Billy Elliot, what changes would you make? How would a Ken Loach Billy Elliot be different?

Well, first of all, it was set during the miners’ strike and I did a documentary during the miners’ strike [Which Side Are You On? (1984)] and met a lot of people there at the time. And the one thing that was apparent was that it was a very culturally-aware time. I mean, the mining communities had creative writing circles. They exchanged poems, particularly the women who were involved, with other mining communities and people who supported them. There were concerts, people came to perform. And the idea that a group of people who were doing that would force a man to cross a picket line for the sake of the 10 or 15 quid it would take for him to get to London is just false. It just wouldn’t happen. I’m not saying that you wouldn’t find one or two idiots who would jeer at what he was doing – I’m sure you would – but, as communities, they were the most artistically aware group of workers I’ve ever known.

|

| Loach (left) filming Which Side Are You On |

And the evidence is there. It’s a matter of record; it isn’t my romanticism. So I just don’t believe it. Although it would feel it was being quite progressive, there’s some very reactionary, ill thought-out, ill-researched work and ideas behind it.

I actually expected the issue you would call attention to was that the father might suffer far more than he does for his betrayal of his union principles. I was accepting that on face value.

He wouldn’t go through it. He wouldn’t have to. I can’t imagine circumstances in which that would happen. I just don’t believe it.

I also felt you would have ended the film with Billy driving away in the bus. He wouldn’t have got to leap around in the West End.

Ha-ha. I dunno. I think the whole premise is flawed. That’s the problem.

I can imagine a Ken Loach film about an older Chantelle [Liam’s sister in Sweet Sixteen, played by Annmarie Fulton]. Maybe you’ve already made it, Ladybird, Ladybird [in 1994])…

Um, yes. That’s an older woman who didn’t have Chantelle’s strength in the crucial years of her life. I mean, Liam’s mother is more in the vein of Crissy Rock [in Ladybird, Ladybird], except that Liam’s mother isn’t a fighter like Crissy Rock. She would take on all comers; she would fight the world. And that was part of the problem, whereas Liam’s mother is defeated and she just has to cling on to whatever support she can find. They’re different responses to similar situations.

|

| Ladybird, Ladybird |

Would you ever consider making a film about the Stans of the world and what’s led them to where they are? [Stan is played in Sweet Sixteen by Gary McCormack]

Um, yeah. Stan was a kid once. He comes from somewhere. He’s learned the world’s a tough place and you’ve got to be pretty tough to survive. He’s a man of limited intelligence and limited ambitions and he’s useful to the bigger guys. His vanity is one of the major features of his character.

I was thinking more of whether you might consider placing him in the centre of things and making an audience deal with this character. I mean, I’m talking about a very “uncommercial” kind of film.

Yes. He loves the idea of himself as a gangster, that kind of guy with street cred and style and all that. And the sad thing is that he’s nothing of the sort. He’s another guy who’s full of illusions about himself. And that’s the kind of myth he’s built around himself. So, yes, Stan’s an interesting character.

|

| Martin Compston, Sweet Sixteen |

What do you think about the fact that Sweet Sixteen was given an MA rating in Australia?

That’s OK. That’s OK. In Britain, it was 18! And that was ludicrous. It wasn’t because of any violence or story. It was just because of one word in the dialogue which they said was used aggressively. I mean it’s pathetic. So I think 15 is what we were expecting. I mean, it’s not a film for young children, obviously. But kids the age of Liam should be able to see it because it’s their world.

How do you go about finding young actors like Martin Compston? You find them all the time.

Well, you just look and look, you know. Try them out and look again. We must’ve seen several hundred, I suppose. There’s always a lot of talent around, really. I mean, again, that’s axiomatic. Every school you go into you’re gonna find half a dozen kids who’re quite bright. So you just keep looking and looking until you get a shortlist and then somebody emerges as the one who’ll really make it work. It’s not so difficult, Tom. It’s just a question of using your common sense really.

Behind the camera, you tend to work regularly with the same people. You know, Barry Ackroyd, Rebecca O’Brien and the others. How important is this kind of collaboration (a) to you and (b) to your working methods?

I think it’s very important because we sort of work out things together really and it relies on everybody’s craft to carry it through. I mean, Rebecca is very important, Barry, Martin Johnson, the designer, the editors, the sound recordist. Everybody’s contribution has been honed over the years. Take them away, I can’t do anything.

I mean, it’s an absolutely collective enterprise which is why I hate it when it says, “A Film By…” and then the name of the director. I suppose you could say “A film by Kodak” and that’d be about as accurate as you could be, but it’s certainly not “A Film By Me”. I mean, it’s a film by a bunch of us really.

Yes, but everybody always has to blame somebody and it’s always easier to pick on an individual.

Ha-ha.

Thanks for your time.

OK, it’s been nice to talk with you. All the best and thanks for not speaking about the cricket.

Ha-ha. Well, India has New Zealand on the ropes at the moment.

Oh, do they? I haven’t heard the scores.

Yes, they’ve got them three for 30-something.

Yes. India look a good bet to me. I mean they’re the only ones who might challenge Australia.

Yes. And I was politely avoiding the cricket too.

Ha-ha. OK. All the best.

*******

Editor's Note: This is the second part of an interview with the director Ken Loach. It was recorded by Melbourne film critic Tom Ryan as the basis of a feature article for The Age when the film Sweet Sixteen was first released. Part one can be found If you click here The Previous posts in this series have been devoted to conversations with Colin Firth (Part One) Colin Firth (Part Two) Lawrence Kasdan (Part One), Lawrence Kasdan (Part Two) Costa-Gavras Jonathan Demme (Part One) Jonathan Demme (Part Two) Click on the names to read the earlier pieces

Thursday, 23 December 2021

Streaming on MUBI - Janice Tong examines the beginning and the end of Jean-Pierre Léaud - LES QUATRE CENTS COUPS (François Truffaut, France, 1959) and THE DEATH OF LOUIS XIV (Albert Serra, France, 2016)

Jean-Pierre Léaud, Francois Truffaut, 1959

On the eve towards one’s final destination, one is afforded a glimpse of a golden youth; textures and colours so close in front of your eyes that they are made indiscernible from your present circumstance, this amber renaissance, where your vision fills with the yearning of yielding lovers whose lips and limbs curve about your body; thought-flights, high-rise, sunken dreams. You are no longer present. Because here, your eyes are myopic and your tongue is dried up and could only taste the thin veil of this chimeric vision. A temporal gulf that lies eternally between you and your beating heart.

Remembering Truffaut at the anniversary of his death - 21st October 1984, I watched two films on either side of that date. One by director Albert Serra, La mort de Louis XIV, and the other, Truffaut’s unforgettable debut Les quatre cents coups; these two distant films fused together by a singular cinematic presence, that of Jean-Pierre Léaud.

Seeing the great Léaud laid out on his death bed (above) as Louis XIV was a revelation. He exuded a sense of mortality we all feel at times, of that unspeakable destiny that awaits those who walk on this earth. The key that consoles the yawning abyss is conjured in the word ‘waiting’. It is certain that the idea of death is never too far away from one’s thoughts; even when holding an infant, their father already dreams of his child’s fate, of what lies ahead. The head of death darts up and although immediately extinguished, but we know all too well that it is simply lurking behind the sun. Into the shadows and vales of death, we must all turn.

Watching Léaud in La mort de Louis XIV, I saw the Sun King. But in him, I also saw the many incarnations of Antoine Doinel. Antoine’s youthfulness and misadventures had cast its glory days in Léaud’s lived-in face. Here, it is framed by highly decorative wigs. His reclined body incumbent and inert is fully dressed, adorned in intricately embroidered brocade - oftentimes gold and crimson jacquard; and sometimes in French blue with gold details of an oriental landscape. He is always both cushioned and covered by dark wine-red velvet furnishings, an embossed pillows and coverlet. He is a feast for the eyes, despite the gruesome onset of gangrene that would eventually take his life (from a blood clot). First consuming his entire leg, it looked as though the King had donned a black stocking when in fact he was putrified from within. Nonetheless there is no mistaking that Léaud was Louis, and his wig is a lion’s mane. Perhaps this is what director Nobuhiro Suwa innately saw in Léaud when he casted him as veteran actor, Jean, in his very fine film Le lion est mort ce soir (2017). Even in these final days, there is a sense of arrogance and incredulity in his very defiance of death: Doinel had grown stately.

Serra gave utmost care to the treatment of this film. He and his research team consulted physician’s texts, historical manuscripts in order to provide crucial measures of historic accuracy. This intimate retelling of the final days of Louis the Great, who died four days ahead of his 77th birthday on the 1st of September 1715 is a quiet and sombre affair. Louis XIV acceded to the throne at only four years and eight months of age and ruled France for a period of 72 years and 110 days, the longest of any monarch. The many facts of those last days and hours were taken from a specific source, the memoirs of Duc de Saint-Simon in which the exact words spoken by the King on his deathbed were recorded. But during the editing of the film, all the dialogue was cut from those scenes, so that, in Léaud’s own words, “what you have are what precedes or succeeds them, and with that you’re left with that incredible intensity of the moment.” In that aspect, the dramaturgy came solely from Léaud’s stately presence. This is acting in micro-movements: the mood and tone created by a flicker of the lids, a prolonged gaze, grimaces or the sharp drawing of breath. Our approach to the great King in his reduced capacity is a more intimate affair; to read these diminutive traces that only the First Valet to the King, exquisitely played by Marc Susini, was able to discern and decipher.

This grand film was shot on a small budget (less than $1M), and in 15 days without rehearsals. The methodology of Serra’s artistry demanded the actors be fully present in their various incarnations of this historical moment. And I for one, deem this piece of cinema to be a spectacle, including the singular prolonged moment of direct address, (and I’ve always loathed the breaking of the 4th wall - it most certainly didn’t work in Orlando (1992), or one of my favourite Christophe Honoré’s films Dans Paris (2006), in Amélie (2001) it was almost passable). I found myself strangely mesmerised by Léaud’s gaze, it was not the usual complicitness that many such direct address want to extract, but instead, this gaze was invitational in tone, and perhaps it is the delicateness about his eyes that made this encounter more alluring. A fitting Kyrie from Mozart’s Mass in C Minor conducted by Helmuth Rilling with his Bach-Collegium of Stuttgart requests our presence to lock gazes with the King.

Unlike a modern take on Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, a good approximation is to be found in Ashish Avikunthak’s wonderful film The Churning of Kalki (2015), where a continual deferral of the whatever it is you are searching for escapes you; Serra’s film provides a glimpse into the abyss rather than the infinite circumnavigation around its edges. This is an affecting reminder of what is lurking in our presence.

|

| The innocent Jean-Pierre Léaud, The 400 Blows |

Whilst La mort de Louis XIV is not Léaud’s final film. (It was already succeeded by four others). I cannot help but see this film as a bookend to his first - François Truffaut’s brilliant Les quatre cents coups; a film that continues to sing inside my breast long after my last viewing of it; and I would situate it amongst the very best of the French New Wave. Immensely touching but impossibly light. Liberty, youth, brotherhood are bounded in sensitivity and timelessness. There’s a certain feeling that’s intrinsic to all fourteen year olds, (as Guy Gilles rightly says in his film Love at Sea (1964), “you have to be very young to feel this”. Note also the young Léaud has a cameo role in this film), that breathless ecstasy of adolescence, the abandonment of all ego or judgement, fuelled by a mix of daring and innocence. Truffaut found the alter-ego of his childhood in Léaud; and whilst we are familiar with the story of how Léaud won the role of Antoine Doinel, (he was cast out of more than 400 boys who came to the casting call after Truffaut put an ad in the newspaper France-Soir, there’s a fantastic little audition clip that shows the young Léaud who had clearly skipped school and travelled all the way to Paris by himself for the audition; he was at once sweet, cocky and sure of himself). It is this exuberance, naïveté and arrogance that Truffaut managed to capture on screen that made this film so special. But more than that, Léaud was in many ways Doinel. This fictional character was created by Truffautand Léaud through a further four films: Antoine and Colette (1962), Stolen Kisses (1968), Bed and Board (1970) and Love on the Run(1979). Note that all except for Stolen Kisses and Love on the Run are available to watch currently on Mubi.

Returning to Les quatre cents coups, the film opens with the unforgettable and heartbreaking score by Jean Constantin; we see passages of various neighbourhoods and streets of Paris through the window of a passing car with the Tour Eiffel always in the distant horizon. We wonder where this car’s traveller would take us; perhaps this is a jump forward to when Doinel was taken to the reformatory and the gaze is that of Doinel’s leaving a city he knows; well before his escape. His ability to redirect his gaze, to confront us, his audience and judge. In the semi-blurred freeze frame that ends the film, Truffaut’s young Doinel reminds me of the famous photograph of 16 year old Arthur Rimbaud by Ìätienne Carjat that I’ve grown to love so much. Of course, Doinel cannot be compared to Rimbaud in temperament or talent, but nonetheless, the two images share the same delicacy around the mouth and eyes to only be found in boyhood.

|

| Balzac and Gitanes |

“Faire les quatre cents coups” is a French saying that literally means “to cause trouble in every possible way”, and that is how society and those associated with its regulators would see of Antoine. The title is more a critique of those types of enforcements and agencies of authority. Instead, this film is a heady mixture of a vulnerable time in life, a youth who is coming to his own, often misunderstood, the lack of guidance from figures of trust, and the love-hate relationship with his parents propelled him towards his own search for identity. As a semi-autobiographical film, Truffaut’s lens is not clouded with sentimentality, having ditched the conventions of cinema from the forties and fifties, the nouvelle vague reinvented ways of storytelling - jump cuts, filming on the street, non-diegetic inserts, and improvised scenes. All this allowed Truffaut et al to capture the esprit of that time; those fleeting moments before a child becomes a man; that very fragile husk of freedom before one becomes accepting of the life one needs to lead (or sometimes reject).

It’s easy to see why so many (myself included) seek a different life in the darkened theatre, where something bigger-than-life enfolds and carries us in its slipstream. These are dreams of a different nature, an offering up of alternatives to the disenchantments of life. And this brooding sentiment became fastened to the soixante-huitards; a manifestation that is still within our collective consciousness. Reminders of this spirit live on in the graffitied street corners around the 5th even today. To see them our hearts are opened once more. The revolution that never took place is actually a revolution that never ended.

Rather than raising hell, Antoine leaves your heart to ache in shreds long after the word FIN appears on screen.

|

| The semi-blurred freeze fame – ending the film in media res |

The two films bookend what is a search for the truth in cinema. The cinéma vérité authenticity in both Serra’s and Truffaut’s film peels back the saturated layers of luxuries and complexities technology has brought to 21st century filmmaking. Let’s settle with the heartbreakingly observed poetry in the boy and the king.

Tuesday, 21 December 2021

Streaming on Paramount + - Rod Bishop dives deep into SOUTH PARK: POST COVID – THE RETURN OF COVID (Trey Parker, USA, 2021)

Everything that follows is spoiler, including the excess of subplots and the confusing time-travel

PART 1 POST COVID

It’s been 38 years since Covid started and the South Park boys are now middle aged.

Stan is an online whiskey consultant and co-habits with his Amazon Alexa, a hologram assistant with a serious relationship attitude. Stan can always turn her off and on.

Kyle, now a guidance counselor at South Park Elementary, has summoned Stan and the rest of the gang back to South Park. Kenny grew up to become a famous wealthy physicist, but he really has died this time.

Jimmy has become a late-night talk show host - “the king of woke comedy” - and his material is so lame, there are no jokes, no punchlines, just forced canned laughter from his woke audience. Jimmy, too, heads for South Park cancelling his scheduled guest, the “First Lady Tom Kardashian”.

And Cartman? He’s converted to Judaism, with his trademark beanie turned into a yarmulke. Insisting on being called a rabbi, he arrives with his Jewish kids and smooching over his Jewish wife.

At Kenny’s wake, we see Token Black (now a cop) and Clyde who is refusing to get vaccinated, thereby causing the military to quarantine the town.

Clyde: I can’t get vaccinated because I’m allergic to shellfish

Wendy: Clyde, there’s no shellfish in the COVID vaccine

Clyde: I know, but I read sometimes in the lab where the vaccine is made, if somebody ate shellfish, then it can get cross-contaminated and leave left-over residual shellfish-ness

Jimmy: So, you’re saying you won’t get the COVID vaccine out of shellfish-ness?

Clyde: Yes, that is correct. Just a general sense of shellfish-ness

Kenny has supposedly died of the Covid Delta+ Rewards variant, but the boys decide he was really killed trying to investigate the origins of the virus and they set out to expose the truth.

Stan confronts his dad, Randy (formally South Park’s No 1 marijuana dealer) at the Shady Acres Retirement Community, now tricked up to look like a set from Bladerunner.

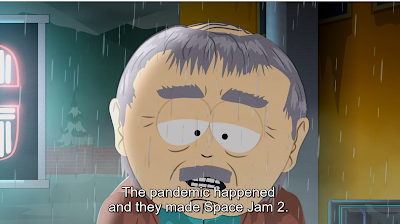

Randy: When the pandemic started you were only a kid. You don’t remember the pain we all went through…we as Americans went through so much. First, that incompetent jack-hole was elected President. Then the pandemic came and then the race wars. And then just when it seemed like we’d turned a corner,Space Jam 2came out and we all just kind of gave up.

Randy then admits to having started the virus when he had sex with a pangolin in China, but his new conspiracy theory blames China for setting up the pangolin sex in order to steal the USA of its “tegridy” - Randy’s own propriety dope crop.

The gang retrieve a USB stick from Kenny’s corpse – it’s up his bum – and watch a video of Kenny attempting time-travel to stop the pandemic.

In a cliffhanger ending, we are introduced to Kenny’s assistant Victor Chouse at the South Park Mental Asylum Plus. But we see it’s a mispronunciation: Victor Chouse is really Victor Chaos…it’s Butters!

PART 2: THE RETURN OF COVID

A new Covid variant, called the Kenny McCormikron, has all of South Park quarantined behind wire fences.

It’s a rain-soaked Bladerunner set and “nobody is allowed in or out for the next 20 to 30 years”.

Randy March has escaped from the Shady Acres Retirement community, clutching his last Tegrity Farms marijuana plant. After beating up some Shady Acres workers who have tracked Randy down, Token Black (flashing his badge) takes Randy to Kenny’s lab. There, with Kyle, Stan, Wendy and Jimmy, they find Kenny’s computer can’t be opened without a voice command from Kenny’s partner Victor Chouse, now in the South Park Mental Asylum Plus.

To make matters worse, how can they find the aluminum foil they will need for time travel? All supplies are stuck on cargo ships off the Long Beach coast.

At the Asylum, they find Victor Chouse is really Butters, who has been calling himself Victor Chaos ever since his parents accidently grounded him 16 years ago. Butters is also a full-on NFT (non-fungible tokens) snake-oil salesman and is financially ruining his victims with unique digital art tokens that operate on cryptocurrency platforms.

In the lab, Randy is growing marijuana plants, believing this will save the world. The others, however, plan to time-travel Kyle and Stan back to China to stop Randy having sex with the pangolin, thereby stopping Covid before it started.

Randy: I’m sorry, but focusing on who started the pandemic is racist…you people need to stop trying to change the past. COVID happened. Space Jam 2 happened.

Later, Randy is sitting in a Bladerunner rain:

Randy: The pandemic happened and they made Space Jam 2…soon there will be a Space Jam 6 and 7 and 8…Like tears…in rain.

Rabbi Eric Cartman, with his wife Yentl and their three children Moisha, Hackelm and Menorah, use the South Park Church for his Foundation Against Time Travel (FATT) designed to prevent Kyle and Stan from stopping Covid and thereby depriving Cartman of his new, idyllic Jewish life and family.

Cartman starts his Foundation, recruiting Butters and the unvaccinated Craig (“the vaccines grow titties on your head”). Having stolen the time travel equipment and set it up in the Church, Cartman reveals his plan to send Clyde back in time to kill Kyle before he grows into an adult and then time-travels back to stop Covid.

Partially wrapped in aluminum foil, Clyde, Stan, Kyle and Cartman all time-travel to the past where Clyde tries to shoot the young Kyle, but instead is shot by a reformed Cartman who sets about restoring his friendship with his friends before they travel back to their adult lives.

Randy, meanwhile, has grown a new marijuana crop and gives it away for free. It’s so good, everyone starts forgiving everyone for the way they treated everyone during the 38-year pandemic.

This even includes the rioters who attacked the Capitol Building who now stand holding signs OUR BAD, WE WENT A LITTLE BONKERS, OOPS, WE ARE Q AND WE ARE SORRY TOO

Rioter: We were like, ok, let’s storm the Capitol! And that was just a bad idea, you know, we were just going a little bonkers there. We shouldn’t have stormed the Capitol.

The listening crowd cheer and hold up signs WE ALL MAKE MISTAKES, NOBODY’S PERFECT, CAN WE START OVER?

The basketballer LeBron James is on a film set: I’m sorry, I’ve thought about it and I just can’t do Space Jam 2. I just can’t support Chinese censorship.

Producer: Oh, yeah? Well, if you’re not gonna make Space Jam 2, then I’m not gonna make Space Jam 2! And nobody’s gonna make Space Jam 2!

The film crew cheer and throw scripts into the air.

And Cartman? Last seen drunk and homeless on the street, screaming: Fuck you guys!...Fuck you, Kyle! Fuck you, Stan! Fuck you, Butters…