|

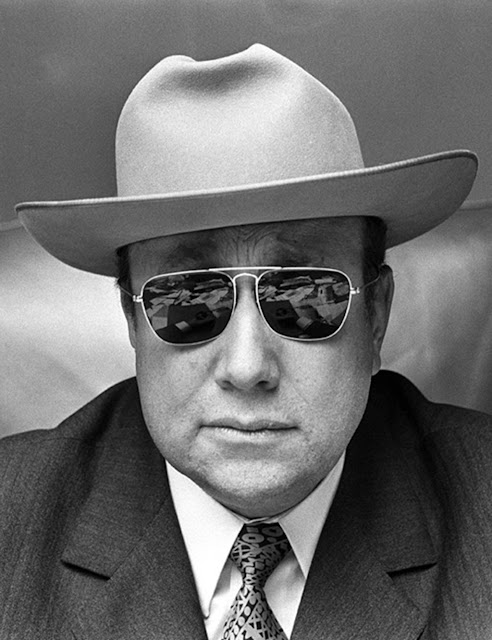

| Ph: Courtesy Phillip Adams |

Monday, 31 August 2020

Sunday, 30 August 2020

At the Randwick Ritz - A Retrospective program for September including more Fellini, more Hitchcock, David Lean, John Huston, Frank Capra and every official Bond.

Massive September Retro Calendar at Ritz Cinemas, Randwick

Media Release August 31, 2020

SEPTEMBER RETRO CALENDAR

Every single day at Ritz there's a retro film playing, with some days screening up to five retro choices at various times.

The Bondathon has begun, with every (Eons Productions official) James Bond film playing in chronological order of release on Wednesday and Sunday nights at 007pm, in the lead up to the release of the 25th film in the series, No Time to Die, on November 12 this year. September sees the end of the Sean Connery films; Aussie James Bond George Lazenby's one film, the fantastic On Her Majesty's Secret Service on Father's Day (Sunday 6 September); and the start of the Roger Moore films round out September.

This month, some of the featured programs include the continuing Hitchcock Retrospective, which started last year at Ritz and sees Hitchcock's films playing in chronological order of release every Wednesday and Sunday at 2pm. The retrospective concludes on Wednesday 23 September with Family Plot.

Then there's the Fellini Centenary Retrospective, celebrating what would have been Italian maestro filmmaker Federico Fellini's 100th birthday this year. Fellini's films have been screening every Monday night at 7pm, but they continue through September every Tuesday night at 7pm.

Babs Fest highlights nine of Barbra Streisand's best films on Monday nights at 7pm starting from Monday 31 August.

The Star Wars re-release seasons continue with the celebration of the 40th anniversary of Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back, screening nightly at 6.30pm for a week from Thursday 10 to Wednesday 16 September.

Other highlights include 70mm screenings of Aliens, Titanic and Lawrence of Arabia; a double feature of Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure and Bill & Ted's Bogus Journey on Saturday 5 September at 4.30pm; and a meow-along/dress-up screening of the blockbuster musical Cats on Friday 4 September at 9pm with 'Rum-Tum-Tugger' cock-tales available from the Ritz Bar.

FULL RETRO PROGRAM

Tuesday 1 September

7pm – Nights of Cabiria (1957) – Fellini Centenary Retrospective

Wednesday 2 September

2pm – Torn Curtain (1966) – Hitchcock Retrospective

7pm – You Only Live Twice (1967) – Bondathon

Thursday 3 September

7pm – All the President's Men (1976)

Friday 4 September

9pm – Cats (2019) – Meow-along Screening

Saturday 5 September

1pm – Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958)

4.30pm – Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure (1989) + Bill & Ted's Bogus Journey (1991) – Double Feature

Sunday 6 September

2pm – Topaz (1969) – Hitchcock Retrospective

4pm – Nights of Cabiria (1957) – Fellini Centenary Retrospective

7pm – On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969) – Bondathon

Monday 7 September

7pm – Hello, Dolly! (1969) – Babs Fest

Tuesday 8 September

7pm – Big Trouble in Little China (1986)

Wednesday 9 September

2pm – Topaz (1969) – Hitchcock Retrospective

7pm – Diamonds are Forever (1971) – Bondathon

Thursday 10 September

6.30pm – Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back (1980) – 40th anniversary

7pm – Alien (1979)

Friday 11 September

6.30pm – Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back (1980) – 40th anniversary

9pm – Aliens (1986) in 70mm

Saturday 12 September

12pm – It's a Wonderful Life (1946)

3pm – Aliens (1986) in 70mm

6.30pm – Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back (1980) – 40th anniversary

7pm – Badlands (1973)

Sunday 13 September

2pm – Frenzy (1972) – Hitchcock Retrospective

4pm – Cool Hand Luke (1967)

6.30pm – Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back (1980) – 40th anniversary

7pm – Live and Let Die (1973) – Bondathon

Monday 14 September

6.30pm – Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back (1980) – 40th anniversary

7pm – The Owl and the Pussycat (1970) – Babs Fest and 50th anniversary

Tuesday 15 September

6.30pm – Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back (1980) – 40th anniversary

7pm – Variety Lights (1951) – Fellini Centenary Retrospective

Wednesday 16 September

2pm – Frenzy (1972) – Hitchcock Retrospective

6.30pm – Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back (1980) – 40th anniversary

7pm – The Man with the Golden Gun (1974) – Bondathon

Thursday 17 September

7pm – Being There (1979)

Friday 18 September

8pm – Titanic (1997) on 70mm

Saturday 19 September

2.30pm – Titanic (1997) on 70mm

Sunday 20 September

12pm – Giant (1956)

2pm – Family Plot (1976) – Hitchcock Retrospective

7pm – The Spy Who Loved Me (1977) – Bondathon

Monday 21 September

7pm – What's Up, Doc? (1972) – Babs Fest

Tuesday 22 September

7pm – I Vitelloni (1953) – Fellini Centenary Retrospective

Wednesday 23 September

2pm – Family Plot (1976) – Hitchcock Retrospective

7pm – Moonraker (1979) – Bondathon

Thursday 24 September

7pm – Flying High! (1980) – 40th anniversary

Saturday 26 September

2pm – Lawrence of Arabia (1962) on 70mm

Sunday 27 September

12pm – The African Queen (1951)

7pm – For Your Eyes Only (1981) – Bondathon

Monday 28 September

7pm – The Way We Were (1973) – Babs Fest

Tuesday 29 September

7pm – Il Bidone (1955) – Fellini Centenary Retrospective

Wednesday 30 September

7pm – Octopussy (1983) – Bondathon

Tickets and more info available here.

Saturday, 29 August 2020

The Current Cinema - Barrie Pattison reports on the Chinese blockbuster THE EIGHT HUNDRED (Guan Hu, China, 2020)

EIGHT HUNDRED HEROES

The new Chinese film The Eight Hundred, directed by Guan Hu, is a major piece of contemporary film history - or history itself. Touted as a monument to the 70th Anniversary of the founding of the Republic it has been given the full treatment - giant budget, star names and the first use of IMAX cameras on a Chinese film.

Its subject, the 1937 defense against the Japanese advance of the Shanghai Sihang (Four Banks) warehouse on the north bank of Suzhou Creek is a marker in the Chinese national self-image, something comparable to Dunkirk or Gallipoli - or the Spanish Siege of the Alcazar. Retreating Chinese forces left a single regiment claiming they were eight hundred men, though actually the number was near half that. Against all expectation, these held the position for four days and four nights beating back six enemy attacks. The story was made more dramatic and strange by the fact that across the river in sight of the fighting, the British concession was protected from attack under tacit agreement that foreign interests would not be damaged for fear of bringing their countries into the conflict.

The original subject was irresistible to Chinese filmmakers, with a couple of films made at the time, one released silent because the Japanese had occupied the area that had sound equipment and in the seventies it became of one of the great successes of Taiwanese film, Ding Shanxi’s 1976 Ba bai zhuang shi/The Eight Hundred Heroes which managed to employ most of the notables of the then booming Chinese off-shore film industries and was widely shown in Australian Chinatowns. In particular, the last half hour was a suitably rousing action spectacle and that film appears to have established itself as the popular record of the event.

The new production starts with the advance to the warehouse featuring troops who insist they are not deserters but stragglers from other columns. The building formerly used by multiple banks has four feet thick walls which resist easy attack. Japanese close in and sweep through the open entrance only to have a roller door rung down trapping them inside to be slaughtered. They respond with gas bombs like those they have used in other campaigns, with the Chinese using masks and urine soaked scarves to protect themselves.

At this stage we become familiar with several of the stragglers and the officers, recognition which is easier for the home audience spotting performers known to them but not familiar to us. We also discover the film’s most striking and surreal element - the pleasure quarter of the British Concession within hailing distance of the embattled forces. Curious residents gather in the street to watch the fighting just across the river. A British soldier mutters “Mustard gas!” as fumes reach him. The film makes the leisure center more glitteringly opulent than it was in real life, with Western Brand Names recognisable in the signage - RKO and Paramount prominent among them. We later get a clear view of the Coca-Cola sign painted on the side wall of the Sihang Warehouse - decoration or comment.

We are also introduced to a white horse which has been stabled in the building and which Zhang Junyi the young peasant straggler is able to relate to and calm. This one’s a relation to those given (obscure) symbolic value in Viva Zapata or Lawrence of Arabia but as events work out it will be deployed more skillfully in this film’s scheme than those were.

A few of the stragglers have worked out that they can escape the warehouse through the water ways in its basement and start off, only to be faced with the tattooed kamikaze troops attacking - setting up another of the film’s set-piece battles.

When the Japanese work a breach with an earthmover Chinese soldiers strap bombs to their bodies and leap down to their deaths blasting it and shouting their names to be repeated to their families.

A Chinese flag is prepared and a girl scout swims the river with it - intense debate over whether raising it is worth the retaliation it will provoke and the decision that, with confusing signals coming from the Generalissimo, their function is symbolic and this is a suitable defiance. It develops possibly the most impressive of the film’s action scenes with Japanese planes strafing the roof and troops being mown down keeping the flag in position. A Goodyear blimp above observes this from close range and across the river erratic fire sends spectators diving for cover. The final shot of the flag still flying above the smoke of battle is possibly the film’s most stirring image.

At this point the piece changes direction. The Japanese Commander calls for a parlay explaining that he’s being replaced for his failure and his successor will bring up heavy artillery which will end the battle. Xin Baiqing the opportunistic Chinese Press photographer accused of being disconnected from the action finds himself immersed in it. Inside the building, a historic shadow puppet is rigged for one performance for the troops who shower as part of the preparation for death.

The makers assume that the audience is now sufficiently familiar with the characters to follow their individual narratives, not altogether warranted with the old problem of men in uniform looking like one another. These stories are unclear and not all that involving - the soldier for whom cigarettes are his life etc.

However, parallel with this is the development of the far bank. With the defenders being mowed down as they cross the river to safety (and the surrender of their weapons), characters we have seen as spectators become foreground - the girl guides, the school children. Brothel owner Liu Xiaoqing breaks out chests of needed morphine. A British soldier opens fire on the Japanese and, most interesting, the Chinese Opera Troop who have been entertaining are now inserted into the action with cuts of their drama shown unrealistically as studio constructed myth spectacle. The film achieves the intended effect of suggesting Chinese history. Chinese experience is concentrated into this moment.

Realised on an enormous scale with impressive attention to detail (no wooden pistols with streamers here) the film can stand with the Christopher Nolan Dunkirk or Peter Weir’s Gallipolli. However, that’s not the end of the story.

The Eight Hundred arrives in a swirl of speculation, having been pulled from its festival dates and original release last year with hardline Communists complaining about celebration of an event in which the party had not participated and in particular about the glorification of the Chinese flag still cherished by the Nationalists, not unlike the controversy over the Confederate flag in the States. Guardians of Chinese history are quick to ridicule this stance as rewriting truth.

The version of The Eight Hundred now circulating is a quarter of an hour shorter than the originally announced length and there is speculation as to whether there was erratic timing or actual deletions.

This leaves the viewer with mindset problems. Along with the question of whether the film is involving and whether it is accurate, we have the distracting question of what its home country wants it to tell us. Outside the Chinese speaking market, it’s likely to antagonise more than it converts to the Mainland cause as people detect or imagine its message content.

I tend to see this as clouding the issue. The films of the Shaw Brothers, Jackie Chan, Sammo Hung and Tsui Hark gave us a pathway into the Chinese experience without having to stop at any propaganda toll booth. That was one of their appeals and indeed one of the things that filmmakers like Chen Kaige rejected them for.

Here we lose immersion in the scene by pondering whether the captured Chinese troops crucified on the building opposite are a stark example of the savagery of the campaign or are included to justify scenes of Chinese soldiers, some with pistols held to their own heads shooting unarmed Japanese prisoners. The silhouettes of the dead Chinese are seen again in the background of the final night’s action - as a reminder. Do the Chinese continue shooting deserters (that first instance makes it into the trailer) or is the offer to leave taken up by several of the soldiers lined up for the probably fatal battle meant to be genuine. The editing deliberately obscures this. Is the absence of a close up of the Chinese flag an artistic choice or a concession to the ideologue?

As in their John Rabe films, it’s still culture shocking to find Nazi good guys sheltering under the Swastika flag, as the Germans attempt to aid our heroes. The British and Americans are shown with considerable ambivalence.

Film makers second guessing themselves always become ridiculous. Think of Mikhail Romm’s 1937 Lenin on October/Lenin v oktyabre where a foreground silhouette appears in the sixties re-issue obscuring its benign Stalin figure or the voice-over added to the 1943 Lewis Milestone North Star to tell us the Russians aren’t good guys anymore. This is not unlike symbolism seeping into the sixties art film. Is the Church the first thing seen on the return to civilisation in Deliverance because it is the tallest building in the town or because it represents a break with barbarity. By the time you’ve figured that out you’ve lost immersion in the scene.

Apparently the new Zhang Yimou production One Second is having similar problems and the same fog enshrouded Feng Xiaogang’s I Am Not Madam Bovary. Feng is the country’s most prominent film maker and it seems odd that he hasn’t been entrusted with one of these milestone historical epics. His last film to arrive, the New Zealand shot 2019 Zhi you yun zhi dao/Only Cloud Knows was almost perversely noncontroversial. We did see Feng acting in the excellent Mr. Six directed by Eight Hundred’s Guan Hu whose background is in prestige Chinese TV.

It will be interesting to watch the course this one takes in international distribution. At home it’s going gangbusters.

For more detail check Derek Elley’s Chinese Cinema Blog.

Friday, 28 August 2020

Il Cinema Ritrovato Online (2) - DONNE E SOLDATI (Luigi Malerba & Antonio Marchi, Italy, 1955), I CENTO CAVALIERI/THE HUNDRED HORSEMEN (Vittorio Cottafavi, Italy, Spain, Germany, 1964)

|

| Marco Ferreri (l) Donne e Soldati) |

I only picked up on Donne e Soldati when the Facebook chatter got into gear. Not having ever heard of the film or the oneshot duo of film-makers, Luigi Malerba and Antonio Marchi, I hadn’t paid attention at all if the truth be known. But there it was , a film rescued from oblivion because of the involvement of Marco Ferreri as actor, writer and some sort of producer.

Curator of the section Emiliano Morreale describes it as a ‘decentralised’ production, i.e. something not made in Rome and calls it ‘the final practical output of the critical and theoretical work of the Parma cinephiles who gravitated around the magazine “La Critica Cinematografica”. The first script credit goes to Attilio Bertolucci, Bernardo’s father. Who knew.

It’s all about Italians waging war and the general level of incompetence, lack of enthusiasm, readiness to make informal peace and the influence of women in the scheme of things, they being infinitely smarter than the idiotic generals and dukes who line up on each side. Very playful and shot in a manner (lots of mud, grime, crumbling castles and improvised searches for food) that suggests both an acknowledgement to neo-realism and a desire to puncture social norms. A beautiful black and white restoration by the Cineteca di Bologna did full justice to Gianni Di Venanzo’s photography. A real discovery, another notch on Bologna’s gun.

Barbara Frey, Antonella Lualdi, I Cento Cavalieri

By chance the same playfulness is also present in a much more sumptuous effort, again restored by the Cineteca for the same distributor as Donne e Soldati Compass Film, Vittorio Cottafavi’s I Cento Cavalieri/ The Hundred Horsemen. I remember this film getting a supportive review in Movie back in the day, like about 1966, but nobody as far as I know picked it up for distribution or even festival screening here, at least not with subtitles.

Once again there is much amateurish military activity on the part of the Spanish peasants who find themselves being taken over and their goods and women sequestered for use by the invading Moors. The Moors are rather better organised and have matching dashing blue uniforms and gold shields. But canniness and enthusiasm win out. This must have been quite an expensive production in its day. The locations are authentic, the battle scenes with horses and men filmed with great dexterity. An American star, well Mark Damon, possibly fresh from Corman’s The Young Racers was brought in and the scrumptious Antonella Lualdi, previously seen In Chabrol’s A Double Tourbut an actress who made dozens of movies, so many that even Barrie Pattison may have seen no more than half, was the female star. Once again it’s the women who are smart and who save it all and though the chief Moor dies in battle, his second in charge stays on and is involved in the double wedding of the finale.

Some kind of day..

Wednesday, 26 August 2020

Il Cinema Ritrovato Online (1) - LADIES SHOULD LISTEN (Frank Tuttle, USA, 1934), MELVILLE, LE DERNIER SAMOURAI (Cyril Leuthy, France, 2020)

|

| Cary Grant, Frances Drake, Ladies Should Listen |

Ladies Should Listen is part of a strand curated by Ehsan Khoshbakht, dedicated to a "'comparative' retrospective' of Frank Tuttle and Stuart Heisler, 'celebrating brilliance outside the pantheon' and 'inspired by the philosophical and political visions they shared, the similar terrain they walked, which led to them tackling almost the same subjects, albeit in two vividly contrasting styles - each often mirroring the work of his fellow director'. Phew.

There's a lot of assertion packed into that sentence and a number of others in Ehsan's introduction and I imagine some cinephiles might care to take it apart. So... first things first, I dont think the selection, at least as far as I can see has Heisler doing an adaptation of a French bedroom farce like Ladies Should Listen, an early Cary Grant picture from 1934 in which Grant is playing Julian de Lussac, a well to do Frenchman who has put all his money into the purchase of an option to buy a nitrate mine in Chile. The plot involves Grant resolving both this financial imbroglio and a more complicated situation with three different women - a rich heiress, his building's telephone operator and an on the make Chilean and her gangster husband.

The whole farce lasts just an hour and after the initial opening scenes marking Julian's return to Paris just a few sets. The opening has "Falling in Love Again" playing on the soundtrack and its shelter skelter from there via a script by Claude Binyon and Frank Butler adapting Guy Bolton's English-language theatrical adaptation of Alfred Savoir's original. I hope you got that. Grant's buddy is the well to do Edward Everett Horton who plays Paul Vernet who keeps trying to become engaged to Susie Flambeau the bespectacled heiress who keeps hurling herself at Grant.

Grant gives Horton some advice about what women like men to do and as a result Horton throws off his inhibitions to have his way with the heiress, a scene rendered by a gap in time and then her asking him to borrow a pin so that she can repair the torn shoulder strap of her dress. Sex on screen has a million markers.

That's as close as anyone gets to being caught in flagrante and Grant ends up with the money he needs and the pretty switchboard girl played by Frances Drake (Frances Drake?!). Whatever happened to her?

|

| Jean-Pierre Melville |

Melville, Le Dernier Samourai is a 53 minute TV doco made for Arte by Cyril Leuthy about the life and times and movies of Jean-Pierre Melville. It is very good indeed and would serve as a useful primer for anyone about to embark on a crash course of Melville's films, no matter how selective that course may be. There are four contemporary interviews threaded throughout (Taylor Hackford, Volker Schlondorff and two of Melville's nephews) and by turns each of them is complemented with a lot of footage of Melville himself and his film-making confreres. One revelatory moment is a piece of an audio recording done during the film of L'Aine des Ferchaux when Jean-Paul Belmondo explodes and gives Melville the benefit of his views on his film-making technique insofar as it goes with Belmondo. He does call the director "M. Melville".

It seems that Melville fell out with many, maybe most, of his leading actors over time. Alain Delon, Simone Signoret and Lino Ventura all come to explain how they weren't speaking by the end.

A very good example of its kind - well-researched, good archival material and a subject of endless fascination, especially as his thirteen feature films yielded up a higher quotients of masterworks than most and did it notwithstanding much career adversity that ran from the dangers of the French Resistance, early film industry indifference, a catastrophic fire that destroyed his business and personal health issues that saw him join both his father and grandfather in being dead at the age of 55.

Tuesday, 25 August 2020

On Alfred Hitchcock's VERTIGO (USA, 1958) - David Hare ponders what might have been with Vera Miles in the lead

Thanks to Joseph McBride for this terrific shot of Vera Miles in wardrobe tests for Vertigo.

Monday, 24 August 2020

On DVD and Streaming - John Baxter revives the original of THE ITALIAN JOB (Peter Collinson, UK, 1969)

A SELF PRESERVATION SOCIETY.

One pleasure of those periodic lists of the 100 Best British Films is watching worthy pieces of kitchen-sink realism fall behind while one’s guilty favourites rise. Time was when the 1969 version of The Italian Job would not have made the list at all. Last time I looked, it was at 36.

|

| THE REAL STARS |

I have many and varied memories of The Italian Job. The sweetest must be climaxing a talk on stunt people at the National Film Theatre in London with a screening of the film’s wild Mini Cooper drive through Turin, the first time the sequence had been seen in full Panavision and stereo for over a decade.

The second can be condensed in a single image; sitting in a taxi at 4am on a warm Los Angeles night and seeing the film’s screenwriter Troy Kennedy-Martin nailed in its headlights, naked, pink and steaming as a shrimp just out of the boiler.

But more of that later.

Three Mini Coopers, painted red, white and blue, and loaded with stolen Chinese gold, rocket down a Turin sewer while the thieves, led by Michael Caine, bawl an exultant song in Cockney rhyming slang. Could there be a more apt metaphor for the Britain of Mary Quant, the Beatles, Joe Orton and David Hockney?

A little loose around the morality? Don’t worry, sir; we can have that altered in no time. Clothes, in fact, are one motif of the film. After a two-year prison stretch, the first stop for Charlie Croker, Michael Caine’s character, is Carnaby Street, at that time the navel of the fashion universe. After one look at his old outfits, catastrophically vieux jeux, his short-maker sneers, ‘What were you serving, Charles – life?”

|

| SIMON DEE AS SHIRTMAKER AND MICHAEL CAINE |

By all the rules, the film should never have happened, and almost didn’t. It originated with soft-spoken, reticent and politically principled Troy Kennedy-Martin, best known for his 1986 anti-nuclear TV mini-series Edge of Darkness. But driving between London and Italy, where his sister Maureen then lived, he conceived a lean Eurocaper film with a steely edge. The crime would be dangerous, the thugs real, the ending ironic.

Michael Caine made a splash as a working-class smart-arse in Alfie and The Ipcress File, only to lose momentum with Hurry Sundown, a failed 1967 Hollywood debut. This inaugurated a series of duds, including a John Fowles adaptation so awful that Peter Sellers, asked what he’d change if he could live his life over, said, “I’d do everything exactly the same, except I wouldn’t seeThe Magus”

The script of The Italian Job kicked about until - in Caine’s version: there are others - he happened to ask his neighbour at a showbiz lunch what he did for a living. “I just bought Paramount studios for $152 million”, Charles Bludhorn said. “Have you got any scripts that you want to make?”

Michael Deeley was the logical choice to produce, since he had just made Robbery,about that other triumph of British criminal free enterprise, the Great Train Robbery. He wanted the same director, Peter Yates, who later directed the innovative car-chase movie Bullitt. Instead, the job went to little-known Peter Collinson - because, if gossip can be believed, he had friends in the corridors of power.

|

| MICHAEL CAINE, NOEL COWARD, DAVID KELLY (PRIEST) and PETER COLLINSON |

At the end of the first script, the gang stashes the gold in a numbered Swiss account, then loses the number. It ends with Caine’s girlfriend randomly sticking a pin in a list, hoping to hit the right one. In the novelisation of the script, the gang gets the gold back to England, only to be told by Bridger to take it back.Of the ending used on the film, Kennedy-Martin was scornful. "I didn't even write it. Michael Deeley added it after they'd run out of money. Peter Collinson hated it so much he wouldn't film it and made the assistant director do it instead." Today it’s one of the most familiar – and most loved - scenes in all British cinema.

The film needed 16 Mini Coopers, which Deeley assumed British Leyland would volunteer. Not so. “Their attitude,” wrote Caine acidly, “was that they did not need us to sell their cars.” Contrast the attitude of Fiat. Not only did Gianni Agnelli allow Collinson to shoot on the Fiat testing track that runs across the rooftops of Turin. If they replaced the Minis with Fiat 500s, he’d give them all the cars they could wreck. Deeley gritted his teeth, thought of England, and paid retail for the Minis he needed.

English character actors filled the film, from Benny Hill as kinky Professor Peach, disappointed he won’t need to wear a stocking over his face, to Tony Beckley as Bridger’s fastidious lieutenant, Camp Freddy – one of the film’s many jokes based on London slang.

|

| DEREK WARE (LEFT) WITH DRIVERS |

For the escape through restaurants, churches, over the tops of buildings, across a weir and finally down a sewer, Deeley hired L’equipe Rémy Julienne, the best drivers in Europe. Notwithstanding irate café owners who soaped their marble floors to make the cars skid and an attrition rate on Minis that had the production accountant biting his nails, they achieved an effect of seamless expertise.

Though The Italian Job did well on first release, critics and distributors alike viewed this as a Kleenex film, to be used and thrown away. In the US, it flopped. “When I arrived in Los Angeles to promote the picture,” wrote Caine, “I was stunned to open a newspaper and see an image of a naked woman sitting on the lap of a gangster who was holding a machine gun.” He caught the next plane home.

Within a year, all CinemaScope prints were worn out. TV versions retained only the central third of the image. Caine, Deeley and Rémy Julienne went on to better things, but Collinson’s career stuttered along until 1980. His last film, The Earthling, was shot, coincidentally, in Australia.

|

| TROY KENNEDY MARTIN |

Half a century after it was made, The Italian Job seems more than ever a film for its times. Not Swinging London, however, but Brexit Britain, with its go-it-alone bravado and insistence that this is once again a self-preservation society. The film begins with the Mafia almost stopping the heist before it even gets going. Maybe this time it won’t be plucky little England but canny old Europe that wins.

Sunday, 23 August 2020

A Major Revival - The Randwick Ritz has a one-off screening of Jean Renoir's great film from 1937 LA GRANDE ILLUSION

Jean Renoir’s 1937 masterpiece La Grande Illusion is having a single screening at the Randwick Ritz on Monday 31 August at 7.15 pm. Book tickets by clicking here

An eternal favourite of many, La Grande Illusion is one of the peaks of Renoir’s career. The Ritz is presenting a beautiful digital restoration that shows off the film to its best.

Here is a sample of some, from the archives, critical opinion about Renoir and the film.

“My judgment that Jean Renoir is the greatest film-maker in the world is not based on a public opinion poll but purely on my own feelings. It’s a feeling, I might add, that is shared by many other filmmakers. And after all, Renoir is the quintessential moviemaker of the personal.

“La Grande Illusion…is built on the idea that world is divided horizontally by similarities, not vertically by frontiers…(it) is a film precisely about chivalry…The great illusion was to believe that the 1914-18 war would be the last. Renoir seems to consider war as a natural scourge that has its own beauties, like storms or fire. It was a matter of waging war politely as Pierre Fresnay does in the film. For Renoir, the idea of the frontier must be abolished in order to destroy the spirit of Babel, to reconcile men who will always, nevertheless, be separated by birth.” François Truffaut

Pierre Fresnay, Erich Von Stroheim

“How has Grand Illusion held up over the years? It is not enough to say that it has retained its power. Not only has the stature of the film remained undiminished by the passage of time (except in a few minor details), but the innovation, the audacity, and, for want of a better word, the modernity of the direction have acquired and even greater impact.” André Bazin

“his most popular film…an extraordinary achievement. In many ways it is Renoir’s most effective film and also his most accessible…in spite of the elevated nature of the subject matter, Renoir indulged his penchant for the grotesque and for the breathtaking mixture of genres – taking us suddenly from the ridiculous to the sublime.” Richard Roud

Thursday, 20 August 2020

Melbourne International Film Festival (online) - Karl Quinn responds to Tom Ryan and David Stratton about MIFF’s decision to pull THE TROUBLE WITH BEING BORN from its program and reports on his interview with the director Sandra Wollner

Below is a story written by Karl Quinn, senior culture writer at The Age and Sydney Morning Herald, about the Austrian film The Trouble With Being Born, which was due to screen at the Melbourne International Film Festival this month. The story was never published, however, because events took a very different turn, as readers of this blog will be aware, when MIFF pulled the film on the eve of the festival in response to comments by two forensic psychologists quoted by Quinn.

Both Quinn and The Age have come in for criticism from contributors Tom Ryan and David Stratton on this blog over what they have intimated was a "beat-up".

Here Quinn defends his reporting, and offers some background on what unfolded between filing the original story below and the story that eventually did run, some days later.

**********************

Karl Quinn writes:

This story begins a couple of weeks before MIFF opened, when Jake Wilson filed a short review for Spectrum, The Age's weekend culture section, in which he described The Trouble With Being Born as a "detached yet outrageous ... provocation" whose subject matter "is exploitation and specifically paedophilia". Wilson added that the film was "almost enough to make you glad MIFF isn’t running as usual this year. Under any circumstances it’s a uniquely uncomfortable experience, but it would be even tougher to get through in a crowded cinema."

Given that, it was almost inevitable the news desk would want a story, and I was asked to provide one. So I watched the film, found it unsettling and fascinating in equal measure, interviewed director Sandra Wollner over Skype, and wrote - for the news pages, with the likelihood of some controversy clearly flagged - the story you see below.

But that story didn't run. After I filed it an editor asked me to seek and add to it the views of someone expert in the area of sex offences against children. Given the subject matter and the images in the film, that hardly seemed an unreasonable request.

I received responses from three forensic psychologists, two of whom I quoted. All three had serious issues with the film. I fed these responses into the original story, while retaining as much as possible of Wollner's explanation of her intentions. But given the strength of the psychologists' responses, I thought it only fair to share them with MIFF before publication, in case the festival wished to respond.

A few hours later MIFF did respond - by pulling the film.

At that point the story became something else entirely, which is what I reported and what we ultimately published.

Far from a "beat-up", the story arose because I sought multiple viewpoints, and gave MIFF the right of reply. I stand unreservedly behind that, as I do my subsequent report of the criticisms of MIFF by Ryan and Stratton. I concede I did not report their criticisms of my initial report in this second report because it simply seemed too solipsistic to do so.

Regardless of the rights and wrongs of MIFF pulling the film, the fact the festival was online this year was deemed a critical factor, both in the issues identified by the psychologists and the decision made by MIFF. But that point could easily be missed in the responses of Ryan and Stratton published on this site.

Also missed in some of the responses - though not in my reporting - is that while MIFF dumped a film that had been "approved" by the censor, that approval was granted in the form of a general exemption, not a specific assessment of the film in question. MIFF insists that detailed descriptions of The Trouble With Being Born were provided to the Classification Board, as required, and one might argue that those descriptions should have been enough to suggest that this particular film ought to be assessed on its own merits.

One psychologist - responding to my detailed but neutral descriptions of scenes in the film (which she declined to view) - asserted that they likely constituted Child Exploitation Material.

Personally, I think this is unlikely, but I'm no expert. But if she is correct, screening that material - let alone distributing it over the internet - would be a criminal offence in this country.

Had the Classification Board asked to view the film, that matter could have been definitively settled. The fact that no one at the Board did so ultimately left MIFF in the unenviable position of having to play censor to its own programming.

Now, here's the unpublished interview with Sandra Wollner.

******************************

|

| Sandra Wollner with Berlinale Prize |

A film in which an android child has sex with its human "father" is destined to be one of the most controversial offerings at this year's Melbourne International Film Festival.

The Trouble With Being Born, from Austrian director Sandra Wollner, arrives at the digital-only MIFF 68 ½ following its debut in February at the Berlin Film Festival, where it received a Special Jury Award in the Encounters section dedicated to more daring works.

But the slow-burning, barely futuristic tale, which one UK newspaper dubbed an "android paedophile film", also prompted audience walkouts.

Al Cossar, artistic director of MIFF, is unapologetic about its inclusion in the festival's line-up. "The content is certainly confronting, however we do not see it as an empty provocation, but a film that transcends troubling subject matter with substance, craft and voice," he says. "We also hope that any response to the film from audiences – positive or negative – comes from a place that is informed, that people respond to what the film actually is, rather than an idea of what they have in their minds, which may not be reflective of the reality of it."

The relationship between Papa (Dominik Warta) and Elli (the pseudonymous Lena Watson) is inappropriate purely by implication rather than overtly pornographic, though it is almost impossible to miss.

Director Wollner says she knows her film is "strange, weird", and is likely to prompt some strong reactions. But she has been surprised by the personal nature of some attacks – invariably from people who have not seen it.

"We've had some strange responses from the alt.right, saying it's 'praising paedophilia', which is obviously not what's going on there," she says. "Some people have been really angry that I, as a potential mother – I'm not yet – could make this. 'You're able to give birth to children, how could you give birth to something like that?'"

Wollner says she had initially wanted to make an "anti-Pinocchio" film that defied the trope of an artificially intelligent being wanting to become human. It would be a way of exploring what it is that actually makes us human – if not 'memories', which AI can replicate to an astonishing degree of accuracy, then what?

"It's the God question, in a way. Memory is just a very specific way to look at it," she says.

It was her co-writer, Roderick Warich, who first came up with the idea of a sexual relationship between a man and an android "child", but it immediately struck a chord with Wollner.

"I had stumbled upon pictures from a Japanese company selling sex dolls of little kids and pre-teens, that are really life-like, really realistic, and this shocked me," she says. "But it's a doll, it's an object, so where do we draw the line?"

She wasn't interested in making a film about her moral repugnance, though, and she didn't know how to answer the question of what impact such things have – "does it do any good, by letting people live their sexual fantasies with an object, or is it triggering something?"

Rather, she says, "I was more interested in doing a film about the fact this exists ... to see the AI as the mirror of the human soul, of the darkest abyss of the uncanny valley, where there's no light. So I needed to go down this path."

Anyone unconvinced that "this exists" need only look to the fact that last week anti-pornography campaign group Collective Shout pressured Alibaba into removing all listings for "child sex abuse dolls", after attacking the online retail hub for profiting "from normalising the abuse of infants by facilitating users' fantasies of raping a child".

But what of the real child actor who plays Elli? No matter what the intellectual justifications for the film, does it not raise serious duty-of-care issues?

Absolutely, says Wollner, which is why the then-10-year-old was given a false name, wigs, and a heavy silicon mask, applied fresh each day, to hide her identity. "You would not recognise her if you saw her in the street," she says.

The script was shared in advance with the girl's parents, "the nicest family I have ever met". A psychologist with expertise in child sexual trauma guided Wollner through the language she should use in explaining situations to Lena; the child was talked through the subject matter in "child-appropriate ways"; and nude scenes were filmed with her in a flesh-toned bathing suit, which was digitally removed in post-production.

"These matters are always scary," says Wollner. "It's very important how you work with the kids."

One challenge that has so far been insurmountable, however, is that Lena is too young to watch the film. "I think it's weirder for her that she cannot show and see what she did."

Ultimately, of course, Wollner cannot know for certain that Lena's involvement in the film will prove benign.

"I've thought about it a lot, what's it going to be like when she discovers her own sexuality, will it do something to that," she says. "Working with kids you always force, in a way, something on them, but we did our best [to be] transparent.

"She comes from such a healthy environment, and knows it's just a game, that I don't think there will be any trauma."