A WAR Tobias Lindholm, Denmark, 2015, 115 minutes

I imagine it would be very difficult for any war film to substantially avoid cliche since the genre is quite possibly the most sustained in cinema history. I myself grew up with the almost endless round of British films about the Second World War and just about everybody in Eastern Europe and Russia must've had similar experiences for the endlessly repeating films of the Great Patriotic War. So in this earnest and very well produced story of a company of Danish soldiers in present-day Afghanistan we find almost all of those cliches.

I imagine it would be very difficult for any war film to substantially avoid cliche since the genre is quite possibly the most sustained in cinema history. I myself grew up with the almost endless round of British films about the Second World War and just about everybody in Eastern Europe and Russia must've had similar experiences for the endlessly repeating films of the Great Patriotic War. So in this earnest and very well produced story of a company of Danish soldiers in present-day Afghanistan we find almost all of those cliches.

Captain Claus (Pilou Asbaek – a regular of the director Tobias Lindholm) who is entitled by virtue of his position to remain within the compound of the Danish troops, nonetheless goes out on patrol with them following the especially brutal and bloody death of a young, fine looking Danish trooper – to bolster morale (cliche one). He is ably supported on a "personal level" by his 2ic played by Dar Salim. Meanwhile, back at the ranch, sorry, I mean back home in Denmark, Claus's beautiful wife grows increasingly anxious about him and the increasingly aberrant behaviour of one of their three children. The company of men in the field is bored, probably not wanting to be where they are. But they display overwhelming loyalty to their boss.

Scenes in Afghanistan occupy about the first half of the film. Wherever they were shot it certainly wasn't Denmark, because the sense of a genuine desert country, possibly Afghanistan itself, of a battle zone and modern soldiers and soldiering (there is absolutely no spit and polish amongst any of the troops, and I warrant that I did not see a salute at any time at all), were all, so it seemed to me, faultless. The "haze of battle" with the troops constantly in radio contact between themselves and home base, with numeric coordinates being rattled off and continuing uncertainty about the level of appropriate response, seemed to me well-nigh perfect. This may reflect the fact that the film which runs for 1 hour 55 minutes does not seem to be at all long.

The critical inciting event is the order by Claus to return fire in an Afghan village where the company has come under attack on a particular building which may, or maybe not, contain civilians. Rules of engagement for returning fire in such circumstances require confirmation that enemy soldiers are present and it is quite possible that my concentration lapsed at this point, uncertain whether Claus knew that there were rebels in the particular building, thought there were, or ignored the possibility because of the intensity of combat. That was a crucial lapse on my part but at the same time I don't think the scene was particularly clear. In any event it subsequently becomes clear that the gung ho days of old don't apply, at least to the Danish army. With everyone else, especially apparently the Americans, whenever there is the slightest serious sphere of "the enemy", all hell lets loose, with complete impunity.

Thereafter more senior officers arrive at the compound to interview the officers and men as to the prior action. This seemed to be handled quite perfunctorily that I would have found this aspect more interesting had more treatment being given to it. It's pretty clear that the senior officers have no loyalty to anyone, especially an officer in the field labouring under all the difficulties one might expect and indeed which the viewer sees. Claus is returned to Denmark to face trial for breaching orders of engagement. He has his own defence counsel,Soren Malling, so along with Mr Malling, Mr Asbaek and Mr Salim we have all the regular male leads that appear in just about every Danish production.

Inevitably with the second half being concerned with a trial, a court room is bound to seem overwhelmingly static, compared to what has gone on before. The Danish court system, at least at this level, is quite informal, so for me, an Anglo-Saxon trained lawyer, I could never quite gel to the idea of this being a place of law. Most reviews emphasise that Claus in the shootout is aware of his breach of the rules of engagement and therefore during the trial he must either confess with all the adverse consequences to himself his family and presumably the reputation of the Army, or give false evidence. Ultimately (spoiler alert) he is saved by one of his senior troopers who swears that he, the trooper, emphatically told Claus of the presence of enemy insurrectionists. This is rather facile because, while not strictly inconsistent with his prior evidence, it has never been raised before.

His family life is now potentially stabilised but the final scene shows Claus sitting in his backyard, smoking and contemplating his future. What would it be, considering his senior officers have apparently abandoned him, some people at least must regard him as being dishonest, so his military career must be in jeopardy. And like all soldiers he must have the continuing concern about taking life. Unfortunately I think this was all handled in rather too perfunctory a way, and the really interesting parts of what could have been an exemplary movie were not touched upon. On the other hand it is hardly for me to tell a director what sort of story he needs to tell. It all seems rather too cold and perfunctory to be emotionally convincing.

Nonetheless, as previously indicated, viewing time passes quickly so the film must be considered quite watchable.

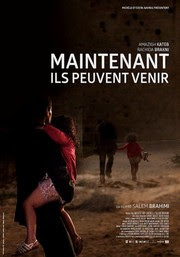

LET THEM COME Salem Brahimi, Algeria/France, 2015, 96 minutes

Let Them Come is the first narrative feature of Salam Brahimi, otherwise known as a director of documentaries. It seems to be a "slow burner" at the recent Festival but nonetheless left a significant mark on those who watched it.

Let Them Come is the first narrative feature of Salam Brahimi, otherwise known as a director of documentaries. It seems to be a "slow burner" at the recent Festival but nonetheless left a significant mark on those who watched it.

In a previous review, I believed I saw a theme behind the actual narrative concerning the individual characters, namely the state of the nation in which the film is set, and indeed exposing "dark" issues, which from a national perspective might best be left untouched.

During the 1990's in Algeria, a nominally socialist country, pretty much kept afloat by oil revenue and remittances from immigrants into France, but highly corrupt and despotic, Islamic terror and fundamentalism of the most incredibly brutal nature developed. Its brutality at the time was overwhelmingly unparalleled and it took the full resources of the state over a long period of time to overcome it.

This is the background to the film concerning a middling civil servant in one of the country's nationalised industries. Seemingly without much ambition or prospects, he is sustained by an active inner life as a writer/poet, albeit unpublished. He seems relatively untroubled by the increasing Islamisation of his country: calls to ensure that everyone attends prayers regularly, the replacement of secular institutions like credit unions with Islamic ones, et cetera. Of course he has good reason to be relatively indifferent, being the unmarried son attending to an absolute harridan of a widowed mother replete with bad temper and psychosomatic illnesses. Substantially under pressure from his mother, the protagonist,Noureddine marries Yasina, a striking and very secular young woman, previously a childhood neighbour and now recently returned to the neighbourhood. He is very used to being put upon!

The film traces the disintegration of the marriage without particular drama, but nonetheless effectively, only hinting that the background of Islamic assertiveness is to some considerable extent involved. She ultimately leaves but Noureddine is troubled by her departure and searches for her, only to find that she has been thrown from her parents' house by her acutely radical father who nonetheless seems to have acquired his radical nature very recently! This leads to a search and it is within these scenes that the best photography and set pieces of the film occur. They are within the Casbah area of Algiers and the harbour foreshore. An area of tightly constricted alleyways, cheap accommodation and poverty, it was pretty much a no-go area even in the days of French colonialism.

This leads to a reconciliation of sorts and the birth of a further child although the penultimate scene or semi-climax is one acute horror for the family. This is the accidental death of the newly born daughter. One then realises that the very first scenes of the film are the give away: Noureddine is finally leaving, presumably for France and it is leaving another woman. Clearly his inner life of writing is nurtured by his country and surroundings and he is frequently shown writing and not participating in family life in the family apartment, to the frequent annoyance of his wife. So ultimately even this final defence of personal integrity is taken from him and he has to leave the country.

There is no particular attempt to explain radical Islamisation. This must've been a temptation for a documentary filmmaker. Instead it simply is, something experienced and needing to be dealt with on a daily perhaps hourly basis, rather than something to be immediately escaped from. I found this aspect of the film, the need for submission to external reality very powerfully drawn. Very well photographed and interesting, at least to me, because it displayed areas I had no personal knowledge of, at least in terms of colour footage. I am pretty well aware of black and white cinematography for some great classic films set in Algiers. The acting seems appropriate and is very low-key.

This seems to me a very appropriate selection for a film festival although ultimately the film is a relentless downer and I can't imagine will have wide theatrical interest. I however was very pleased to have seen it.