|

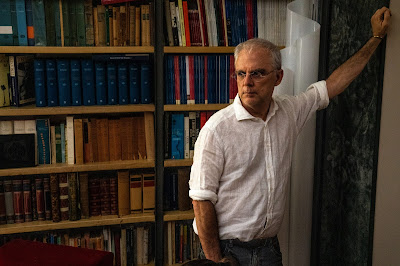

| Director Daniele Luchetti on the set of The Ties – note the word-mural behind him |

Family. That single word with a power to bring comfort and joy and also immense cruelty and destruction. Labyrinthine and pharmakonic (in the sense of Derrida - as both “poison” and “cure”), rarely can you escape your genealogical Eden. The invisible thread that stitches and patterns its roots in a history not of your own choosing. This topiary garden is by design and by the time you’re 5 or 6 years old, it’s formal structure is ingrained to inform your growth and shape your future form.

|

| Luigi Lo Cascio and Alba Rohrwacher as Aldo and Vanda, parents of Anna and Sandro – Giulia De Luca and Joshua Cerciello respectively. |

In Luchetti’s Lacci, timelines and half remembered episodes are woven like remnants of cloth stitched by the thread of time. Sewn together, this tapestry narrates a fragmented story, dense and sprawling, where the viewers are treated with glimpses of an ordinary family’s domestic life and its unravelling.

Vanda and Aldo with their two children Anna and Sandro appear to be the kind of close-knit family one desires. The film starts out in Naples where they were attending a family party, before returning home for bathtime, TV and supper, followed by a story before bedtime. But any familial bliss ends there, because before the end of the night, Aldo (Luigi Lo Cascio) confesses to his wife, Vanda, of having been unfaithful to her, that he is in fact having an affair with another woman and may be in love. Vanda is played by the talented Alba Rohrwacher, (last reviewed here in the 2018 film Lucia’s Grace) whose performance is both vulnerable and cruel. The camera clearly loves her face as it often captures her in close-up. When framed by her curly locks in profile, her classical features make her look as though she has just stepped out of a Botticelli painting. But that aside, Vanda clearly loses it and asks Aldo to leave. Ever so obediently he does, but defiantly, he also does not return home that night, or for many years after that. From here, time is no longer linear, cohesive or rational, and needs to fold back on itself to make sense of what’s happened.

Vanda continues to struggle to keep her emotions in check. Over time she no longer behaves in the manner of a dignified and bereft mother; she has not borne her betrayal well at all. Being jilted has made her bitter and vindictive. She tries to confront him, then she tries to kill herself. But in her every action, her children bear the brunt of the outcomes, silently molding and shaping them. The needle pierces as it stitches all of these episodes together. In a later scene, it is suggested that maybe what Vanda fought so hard to successfully gain, is exactly the opposite of what she wanted; the ties that she made have bound her to a life that was false and unhappy.

-

|

| The tying of the shoelace |

Some of the scenes with the children were incredibly touching. The young Anna and Sandro were played very well by Giulia De Luca and Joshua Francesco Louis Cerciello respectively. The eyes tell their story, flitting from delight at seeing their father, to incomprehensible hurt at the actions of their mother. The bookstore where as teenagers they finally reconnect with their father, was a mnemonic token. Apparently an idiosyncratic way of tying shoelaces was shared between father and son (the daughter missed out), and that metaphor of the shoe lace acts as the tie between the children and father, pulling Aldo back into the noose of the family again. But wounds never really heal, especially with Anna, who as an adult (played by Giovanna Mezzogiorno, last reviewed here in the film Naples in Veils (2017)) has been estranged from her parents for many years. At forty, she bears no resemblance in both physique or sensitivity to her younger self, instead, she bears a closer resemblance to her mother, in both bitterness and entitlement, than she realises.

As for Aldo the word-smith, he has locked his other life inside the chequered box that “can’t be opened”. This, of course, is a metaphor for his heart-box of which the key is also locked within its depths, swallowed up by a web of words. Just like Glenn Gould’s brilliant interpretation of the Goldberg Variations that is played throughout the film, folded within its exterior beauty lies a complex web of form and structure; one can appreciate its charm and delight in its neat unison of notes without having to understand what is hidden within. When I listened earlier this year to Gould’s treatment of the variations during his famous 1955 recording session, with five hours worth of outtakes, it becomes clear that what we have come to know and love is already a distilled version of the truth. The truth, in fact, lies elsewhere.

Aldo wove a protective wall around the apartment with his many bookshelves. These are not necessary books of wisdom, they are instead a kind of word-mural that binds him to this interiority, where truth exists. These are not words that can release him out into the world. Take note of what he has named his cat; it is a word in Latin, so that every time they call to it, they are in fact calling out loud the words “shame”, “the fallen”, “landslide”, “ruined” to the world. As well, the name is the phonetically equivalent of “the beast”, echoing to that which lived inside of him once upon a time, the side that has been tamed, and the name is perhaps a reminder (as the title The Ties does as well) of the collar which chains him to his chosen path.

|

| The box that does not open, Lidia (Linda Caridi) and Aldo |

We will find that what is filled with love and light are but memories, most notably the loving and touching scenes where Aldo was taking nude photographs of his lover, Lidia (Linda Caridi). Their bodies bathed in a golden radiance - the sunlight in Rome is like no other that shines - as though bestowing its citizens with a kind of sacredness. The body is sanctified through this golden lens. And later his precious memory of Lidia is rediscovered in the polaroids taken that golden afternoon. Her image is laid out in the form of a cross on the coffee table, fragmented, a Polaroid-jigsaw, symbolic of the crucifixion of a nude Madonna - when of course she is the other Mary, the whore who has torn apart the family - this other woman is now laid bare, and the magic of that afternoon cannot be restored, (nor her good name), and, just like the destroyed apartment, all is broken, torn, shattered, and left in ruins.

|

| Anna and Sandro as adults, in search of a past |

Having said all that, this film is a lot lighter than what this review has made it out to be. The acting, cinematography, pace, and the intertwining of timelines of these four main characters - they multiply, 4 into 6, into 8 and finally into 10 “different” people - bind the viewers to their lace-like story. Premiered as the opening night at last year’s Venice Film Festival, it is an absolute delight to be able to see it on the big screen in Sydney; especially as my first film at the cinema post-lockdown.

The #ItalianFilmFestival is showing nationally, from the 20th October to the 12th December. (Note that some states finish earlier).