|

| (Click on any image for a slideshow) |

"Lovers come, lovers go

And all that there is to know

Lovers know

Only lovers know."

And all that there is to know

Lovers know

Only lovers know."

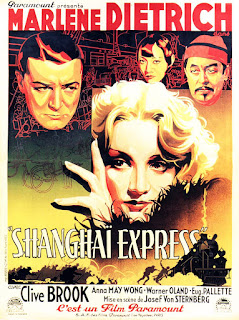

Borodin's sumptuous Polovtsian Dances and the second String Quartet slow movement are subsumed by Andre Previn and Conrad Salinger into a giant Arthur Freed score for Kismet (1955). Mind boggling production design credited to Cedric Gibbons and Preston Ames but ultimately Minnelli's own. Photographed with totally careless rapture by Joe Ruttenberg and choreographed by Jack Cole (and Stanley Donen, uncredited) in the most visually hallucinatory Eastmancolor picture ever made in the American cinema.

Howard Keel winds up the show with this surprisingly melancholy but ultimately Minnellian number, "Sands of Time", screen at top, scored by the great Conrad Salinger with strings and cor Anglais (like the Liebestod from Tristan) which simply defies categorization beyond being one of the supremely final works in the Arthur Freed canon.

Kismet cost Metro more than $3 million and has never (and will never) make its money back. But it lives and breathes still, some kind of insane folly, one of the maddest and most beautiful in movies, every bit of it pushing the parameters of "camp" or (better put by Nabokov) poshlosht with more taste and insider genius than any other 20th century art movement.

It's as though Minnelli dragged everyone who mattered (including Stanley Donen who hated his guts at this point) into the deranged fabulosity. Any movie that can give Dolores Gray (above) so much range, and explore her own considerable skills as an artist while she wears nothing but appliqued chiffon and gold lame is something out of the bag.

Kismet was a show I always disdained, partly from the snobbery of fearing what destruction might be wreaked on classical scores I loved as much as anything in music. If there were ever proof that a movie reborn in a premium form can be a new force, born again, this now four year old Blu-ray is just that, taken from a new 2K, extracted by a forensically perfect transfer from the Eastman O-neg to a new, flawless inter-positive. The disc now seems to be about to explode from the screen pulsing with every grain of Minnelli's color schemes to burn your eyeballs. And the Warner engineers seem to have found the original multi-track audio stems to deliver a hair-raising DTS HD master five channel audio.

It would be more than impossible for even the most dedicated Freedophile to deduce from the constant tracks, cranes and crab dolly shots what is Donen's or Minnelli's. I can only surmise, because there is only one signature Donen frontal crab dolly wide, down to face, back to wide and finish on face (like Audrey's "How Long has this Been Going On" from Funny Face) that the rest of the travellings may as well have been both of them. Plus Jack Cole.

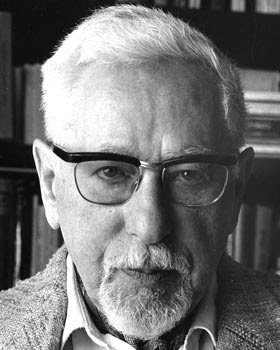

Here are more screens, two studio production shots in B&W from one of the edited documentaries someone at Warner Archive dug out from under a rock, missing for 60 years in the vaults: first of these above is Freed with leads Keel and Ann Blyth. Next screen below is Minnelli, left and Joe Ruttenberg right, with Howard Keel in costume towering over both of them in the centre.

And then the rest.