Editor’s

Note: This is the third part of an expected twelve part series about the German

and American master director Douglas Sirk (Detlef Sierck). The two previous

parts were published on

22 April 2017 and

on

27 April 2017. Click on those dates to access the earlier posts.

Bruce is a

long time cinephile, scholar and writer on cinema across a broad range of

subjects. The study being posted in parts is among the longest and most

detailed ever devoted to the work of Douglas Sirk. In the following text films

in Italics are regarded as key films in the director’s career. References to authors

of other critical studies will be listed in a bibliography which will conclude

the essay.

The Independent years 1943-51

Of the eight features Sirk directed in his

first years in America six were independently produced mainly on B budgets and

are largely overlooked. However, Hitler's

Madman, Sleep My Love and perhaps Lured are to be counted

with his late (melo)dramas The Tarnished Angels and A Time to Love

and a Time to Die among his most personal works. At this time Sirk formed a close long-term

friendship with the actor George Sanders who played the integral central roles

in three important early films.

Tag Gallagher in his retrospective essay in Film

Comment endorsed the filmmaker's belief that Summer Storm and

especially Scandal in Paris as among his best films (a view I endorse

and I would add The First Legion), Sirk being able to work “in a

freedom...able to indulge his fantasies” working with a group of intimate

associates, himself writing the scripts in collaboration. The failure of the Scandal

to gel with American audiences was in all probability something of a turning

point for Sirk in his engagement with Hollywood, a reawakening of the

implications of working successfully in popular genres that he had experienced

at Ufa.

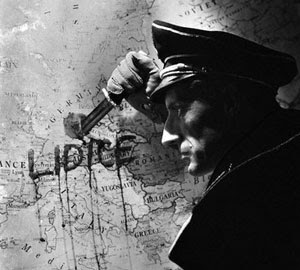

His first film in the U.S., Hitler's

Madman (1943), directed under the name Douglas Sirk, deals with the

Nazi massacre in 1942 of the people of Lidice, a small Czech village. John

Carradine plays Rudolf Heydrich, whom Sirk had once met at a party and said

“behaved and looked just like Carradine [with] the same edginess of speech.” It

was an independent production, filmed in a week, set up by a group of German

emigres shortly after Heydrich's assassination in Czechoslovakia and was bought

by MGM for distribution. It was almost wholly photographed by the great Eugene

Schufftan who could not be credited in this role as he was not a member of the

American Soiciety of Cinematographers (ASC). The studio required Sirk to direct

re-takes of a number of scenes which he felt reduced the “documentary quality”

of the original “in an unsuccessful attempt to make it into another kind of

picture.”

Richard Combs questions Sirk's claim stating that the film “never for

a moment resembling any form of documentary...the grouping of figures,

composition and lighting [and] expressionist use of sets...bringing his German

films to mind.” The most fascinating aspect of the film is Carradine's

portrayal of Heydrich “characterising the 'Protector' in semi-abstract

fashion.” Much attention is lavished on subsidiary characters with “a more

powerful tribute to the ordinary people” than Fritz Lang's quasi-Brechtian treatment

of the assassination, Hangmen Also Die, filmed at about the same time.

|

| John Carradine as Heydrich on his death bed |

|

| John Carradine, Hitler's Madman |

|

| John Carradine as Heydrich |

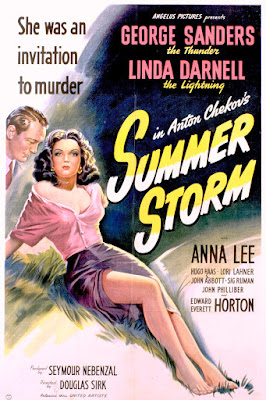

Sirk's second American film was another

independent production, an unrealised Ufa project, Summer Storm

(1944), based on Anton Chekov's only novel, The Shooting Party, with a

strong cast including George Sanders, Linda Darnell, Edward Everett Horton and

Hugo Haas. It was produced by Seymour Nebenzal, an emigre, one of Hollywood's

first independent producers, whose productions in Germany had included G.W.

Pabst's Pandora's Box (1929) and Fritz Lang's M (1931). Sirk co-scripted

the film under the name of Michael O'Hara, re-structuring the novel to contrast

the social forces at work. Michael Stern author of the first book length

monograph in English on Sirk's American films, points out that the first shots

of this film - the close-up of a pair of feet walking on a cobblestone street

with the camera then pulling out to reveal the context is “a figure of style

that characterizes Sirk's mise-en-scène [that] immediately establishes the

primacy of the camera's point-of-view.” Stern sees this opening image as

revealing of Sirk's vision: “so much of Sirkian cinema works to express the

impotence of human will...in the face of fate, accident and...time. The tension

between the characters' needs and desires to break free and the irrevocability

of the human condition is what energizes Sirkian melodrama...We know from the

first shot that Summer Storm will be

a film about uncertainty, doubt and choice.”

The story of a peasant woman Olga's (Darnell) affair with a provincial judge Fedor Petrov (Sanders) which ends in tragedy, is told in a flashback to 1912 from post-revolutionary Russia; the novel was written in pre-revolutionary times. Sirk was interested in bringing out contradictions in behaviour in the portrait of a doomed class, its decay ironically evident in the cynical self-awareness of the judge that leaves him vulnerable to the wiles of 'a bad woman'. Flashbacks and voice-over narration emphasise the 'pastness' of events and the inevitability of Fedor's hopes being forever unfulfilled, “a characteristically dramatic device” suggestive of a “European” fatalism. This is seemingly amplified by Sirk's “ironically detached point-of-view toward characters' folly” although viewed not without humour and a certain compassion. Sirk is pessimistic about the judge's ability to act responsibly, but in leaving options open for him he is more of a realist than a fatalist like Fritz Lang, for example. The drama lies in Fedor's conflicted state of self-awareness evident in his narration. He tells himself that the will to live is “greater than conscience, stronger than pity.” Fedor is responsible for his fate. The film is structured around a density of occurrences and a rich level of darkly ironic humour such as the way several fortuitous interventions let Fedor off the hook when he is on the brink of confessing to murder only to have his hesitation finally force him into destructively precipitous action. Gallagher calls Summer Storm a 'black melodrama': Fedor betrays the love of a good woman (Nadina who becomes a Commissar) for that of a 'bad woman'. Olga is not a classic femme fatale in the film although less of innocence corrupted as apparently portrayed in the novel. Sirk spoke of his interest in the suspense of ambiguity through a certain distancing of the viewer, what he referred to as 'the ambiguity in technique'. This meeting of European culture and Hollywood production style found its critics among those with little expectation that the former can survive such an encounter. Others have praised Sirk for capturing the spirit of Chekov and finding something of an equivalent for his condensed narrative.

A Scandal in Paris (1946) produced by another emigre independent Arnold Pressburger,

is a picaresque, ironic film based on the memoirs of Vidocq who rose from a

life of crime in nineteenth century Paris to become chief of police, with a

“brilliant script” by Ellis St. Joseph to which Sirk contributed uncredited, as

he did on many of his films, with contributions by two other European exiles: a

music score by Hanns Eisler, photography by Eugene Schufftan (again, as in Hitler's

Madman and Summer Storm, uncredited) and the sets designed by

Oscar winning set decorator Emile Kuri. It was not a success perhaps being too

deeply ironic for American audiences but Sirk considered it his best picture:

“if you talk of Art...a European film really – in a total European style.” Sirk

speaks of how he “tried to go beyond realism...almost surrealist” in the way he

presented the story in which he “brought out the irony.” He felt he could have

made a whole series of films out of Vidocq's life but for Scandal he

chose the best part for irony – “the cop-thief oscillation.” It contains some

of Sirk's recurrent themes, most notably that of identity - his attraction to

'in-between' characters of which he felt George Sanders had a deep

understanding; Sirk described his playing of Vidocq as “masterful”. In talking about Sanders and acting with Jon

Halliday, for a man with such a background in theatre direction, Sirk revealed

deep insight into the nature of performance on film. Although he never directed

John Wayne, against the critical grain Sirk recognised him as “a great

actor...an outstanding personage of undiminished power and simplicity –

simplicity not marred by any 'acting tricks'.”

|

| Mimi (Jo Anne Marlowe), A Scandal in Paris |

The first of two independent productions

directed by Sirk on loan from Columbia was produced by Hunt Stromberg who had

previously been a talented and successful producer at MGM under Irving

Thalberg. A bizarrely ironic comedy in Sirk's hands, Lured/Personal Column

(1947) had its origins in a film, Pièges (Personal Column),

directed in France by Robert Siodmak in 1939 with apparently stronger noir elements. Sirk's film is set in London in the

early1900s. A young woman (Lucille Ball), a taxi dancer, is recruited to work

for the vice squad by a police inspector (Charles Coburn cast against type) to

trap a serial killer in the course of which she encounters an insane dress

designer (Boris Karloff). A womanising nightclub owner (George Sanders) becomes

a prime suspect. Lured soon drifts away from any film noir ambience.

Sirk said he got on well with Hunt Stromberg “who liked my direction” and was

given a very free hand on Lured which he co-wrote with Leo Rosten. He

saw it as a continuation in style and the ironic theme of A Scandal

in Paris, also remembering it with affection for the productive

collaboration with the cast, talented Russian art designer Remisoff and

cinematographer William Daniels.

|

| Boris Karloff, Lured |

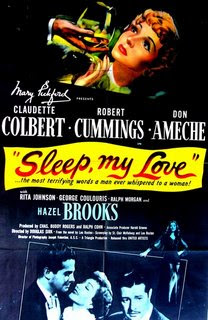

The other indie was for Mary Pickford's

Triangle company with her husband Charles 'Buddy' Rogers as co-producer. Sleep My Love (1948) was also

co-scripted by Leo Rosten from his own story (“a witty guy, but he was pushing

the thing back to melodrama all the time”). The plot resembles that of Gaslight

in which a husband (Don Ameche) is planning the death of his wife (Claudette

Colbert) by persuading her that she is losing her mind. Sirk would have liked

the Colbert character to have been more ambiguous. Joseph Valentine's

expressionistic photography (“a good cameraman although I felt I couldn't bend

his style”) and deployment of the main sets are suitably atmospheric. The

blandness of the characterisations by Colbert and especially Robert Cummins (as

the hero) tends to undercut the melodramatic noir elements.

Sirk finally directed two films for Columbia

with which he had a seven year writer's contract. He wrote several scripts none

of which were filmed. Harry Cohn refused to let Sirk direct until Slightly

French (1948) a musical on which he said he had “no freedom at all,” a

Hollywood-on-Hollywood satire with Dorothy Lamour and Don Ameche “in which what

is real and what is artifice become indistinguishable” (Tom Ryan).

More interesting is Shockproof (1949), with a script by Sam Fuller (originally titled The Lovers) which Sirk “liked tremendously” because it contained “something gutsy” in the story of a law officer (Cornel Wilde) who falls in love with the parolee (Patricia Knight) for whom he's responsible. Sirk found connections in Fuller's script with two plays he had directed in Germany, one having a similar situation, the other a similar theme which Sirk felt he could have made something out of - “a critique.”. Fuller's emotional directness contrasts with the more oblique distancing of Sirk's style and had potential, as Sirk recognised, for a uniquely interesting dialectic which only partially comes into play. The studio brought in another writer to also co-produce and make major changes to the script at the studio's behest including an absurdly unconvincing happy ending although, if this is disregarded, something of Fuller's original intention remains. Sirk saw it as “a very minor picture of mine, and not one that is in any sense my own.” Fed up with Harry Cohn and Columbia's interference, Sirk left the studio, spent a year in Germany and returned to Hollywood “completely demoralized” by the state of the German film industry.

More interesting is Shockproof (1949), with a script by Sam Fuller (originally titled The Lovers) which Sirk “liked tremendously” because it contained “something gutsy” in the story of a law officer (Cornel Wilde) who falls in love with the parolee (Patricia Knight) for whom he's responsible. Sirk found connections in Fuller's script with two plays he had directed in Germany, one having a similar situation, the other a similar theme which Sirk felt he could have made something out of - “a critique.”. Fuller's emotional directness contrasts with the more oblique distancing of Sirk's style and had potential, as Sirk recognised, for a uniquely interesting dialectic which only partially comes into play. The studio brought in another writer to also co-produce and make major changes to the script at the studio's behest including an absurdly unconvincing happy ending although, if this is disregarded, something of Fuller's original intention remains. Sirk saw it as “a very minor picture of mine, and not one that is in any sense my own.” Fed up with Harry Cohn and Columbia's interference, Sirk left the studio, spent a year in Germany and returned to Hollywood “completely demoralized” by the state of the German film industry.

|

| Charles Boyer, The First Legion |

|

| The First Legion |

|

| The First Legion |

End Note

1. In its

displacement of cause-effect logic in a realistic setting The First Legion

represents an early example of art house cinema in Hollywood (see David Bordwell

essay on The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice). It was, for example, very

unusual at that time in Hollywood for a feature film to be shot entirely on

location. The First Legion foreshadows the rise of independent 'art

house' feature film production in America parallel with the New Hollywood. In

the studio era independent features were primarily low budget genre pictures

for release on the lower half of double bills. Sirk's film does have a major

star, Charles Boyer, in for him an untypical role.

|

| Don Ameche, Claudette Colbert, Sleep My Love |

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.