Editor’s Note: This is the fourth part of an expected twelve part series about the German and American master director Douglas Sirk (Detlef Sierck). The previous parts were published on

22 April 2017 (Introduction)

27 April 2017 (Notes on the Weimar and Nazi years)

2nd May 2017 (The American independent years, 1943-51))

Click on the dates to access the earlier posts.

In 1950 Sirk joined

Universal-International where he spent the rest of his American career. He said

he remembered nothing about some of the first seven assignments at Universal

(up to Take Me to Town) which are “best forgotten.” His first

assignment, Mystery Submarine (1951), is a routine war story with “a

poor script.”. Thunder on the Hill (1951) has recurring Sirk themes of

the uncovering of reality masked by pretence and deceit in the story of a woman

(Ann Blyth) sentenced to the gallows after having been wrongfully found guilty

of murder and a nun's (Claudette Colbert) belief in her innocence. Sirk was

adamant that he “wanted this picture to have nothing to do with religion,” with

the entire focus to be on the Ann Blyth character and that the religious aspect

was forced upon him by the studio and the producer “who blew most of the 'A'

budget building a fantastic convent in Hollywood when we could have gone on

location somewhere.”

Sirk was then

assigned two romantic comedies – The Lady Pays Off (1951) in which a

widower and a widow (Steve McNally and Linda Darnell) meet by chance and become

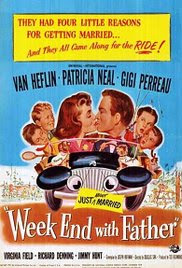

a couple in a comedy with “an uncomfortably sour ending.” Weekend with

Father (1951) with Patricia Neal and Van Heflin is wittier but still

permeated with disquiet, a family comedy “in which the parents rather than the

children are in need of protection.” The couple are nevertheless able to build

a warm relationship (perhaps attributable at least as much to the casting of

Neal and Heflin as to the writing) amidst

the grotesqueries of the bourgeois household. Sirk said he had little feeling

for these films and although he had to stick to the rules of family

entertainment, he restructured them with an emphasis on the situation rather

than the resolution. Sirk also came up with the idea of creating comedie

humaine or contes moraux (tales about peoples' morality) centred on

“average people - samples from every period of American life”. Tom Ryan terms

the above two pictures and the earlier Slightly French, “uncomfortable

comedies.”

Sirk was then

assigned two romantic comedies – The Lady Pays Off (1951) in which a

widower and a widow (Steve McNally and Linda Darnell) meet by chance and become

a couple in a comedy with “an uncomfortably sour ending.” Weekend with

Father (1951) with Patricia Neal and Van Heflin is wittier but still

permeated with disquiet, a family comedy “in which the parents rather than the

children are in need of protection.” The couple are nevertheless able to build

a warm relationship (perhaps attributable at least as much to the casting of

Neal and Heflin as to the writing) amidst

the grotesqueries of the bourgeois household. Sirk said he had little feeling

for these films and although he had to stick to the rules of family

entertainment, he restructured them with an emphasis on the situation rather

than the resolution. Sirk also came up with the idea of creating comedie

humaine or contes moraux (tales about peoples' morality) centred on

“average people - samples from every period of American life”. Tom Ryan terms

the above two pictures and the earlier Slightly French, “uncomfortable

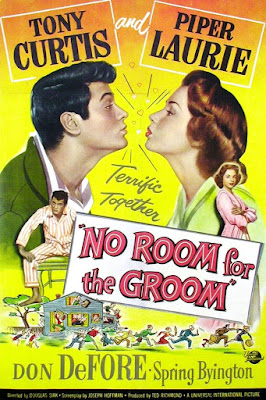

comedies.” The third comedie humaine, Has Anybody Seen My Gal (1952) is a light fable set in small town America in the twenties which plays on the distance between a narrative situation and a character (Charles Coburn) excluded from the action of which he would like to be a part. It was Sirk's first film in colour and the first of his eight films with Rock Hudson. It was also James Dean's first film appearance briefly making his mark in about a minute on-screen. Sirk was the first to identify Hudson's star potential while he was an anonymous bit player. Despite his lack of engagement with these assignments they do presage the 'happy unhappy end' in his melodramas. As Tom Ryan points out, the superficially happy endings in the comedies are “unsettling” to the extent that the underlying issues remain unresolved, none more so than in the most 'uncomfortable' of the series, No Room for the Groom (1952), a savage satire, “an excruciating comedy to watch” in which the forces of greed and hypocrisy appear victorious with the extended family in small town America monstrously intruding on Tony Curtis/Alvah's repeated attempts to consummate his marriage with Piper Laurie/Lee in his own house.

Sirk told Halliday

that he had “no memory of it at all,” but after a re-viewing felt it held up

“never becoming doctrinaire” with Tony Curtis representing the antithesis of

the negative forces, if only by default. Like Kyle Hadley (Written on the

Wind), Alvah is unable to act out his repressed sexuality. In contrast to Groom,

Sirk's final assignment of the 'series' is a musical comedy also set in small

town America, Meet Me at the Fair (1953), in which, according to

Howard Mandelbaum (quoted by Stern),

Sirk “neither deepens nor counteracts the heavy sentiment of the script.” It's main significance for Sirk would seem to

be the first notable appearance of a black character (a boy in the orphanage)

in his films. See Tom Ryan's

discussion of “the uncomfortable comedies” online in Senses of Cinema 74.

What was ignored in the

Cahiers and Screen Sirk issues, as Jean-Loup Bourget points out,

was the relationship between the auteur, the studio and the genre. While Sirk

directed 8 features in Germany between 1935-7 and 29 features in Hollywood

between 1943-59, it is the melodramas of the late American period at Universal

beginning with All I Desire (1953) and ending with Imitation of Life

(1959) that constitute a coherent and structured body of work thematically and

stylistically. This was made possible by the team of collaborators at the

Universal studios, what Bourget called “the Sirk ensemble.” Sirk was nevertheless, by his own account,

very much a 'hands on' if quietly authoritative director, evident in his

reference to “my cutting and my camerawork” (author's emphasis).

He favoured a mobile camera in longer than average takes which the Studio

“didn't interfere with.”

His most important ongoing collaboration was with cinematographer Russell Metty on 10 features, with whom Sirk seems to have had an almost symbiotic relationship on the set describing Metty to Halliday as “a man with a great eye for detail and an appreciation of what I wanted.” Bourget notes that “ one of the innovations of the 'Douglas Sirk' ensemble is the creative, near systematic use of colour, and, to a lesser degree, of the widescreen. Bourget further notes that there were precedents in such use of colour, notably in John Stahl's Leave Her to Heaven (1945), “with the same use of violent colours, symbolising the world of the characters, as are used in Written on the Wind and Imitation of Life.” Metty was also a master of chiaroscuro - he photographed The Stranger (1946) and Touch of Evil (1958) for Orson Welles. Metty was celebrated as “a sculptor of darkness with the camera (Sam Staggs, 220).” As characters move around the room, in a Metty photgraphed film, they often move in and out of shadowed areas in a way unusual for a Hollywood film (Michael Walker in Film Dope). Sirk's collaboration with composer and arranger Frank Skinner began on the comedies to which Sirk was assigned shortly after commencing with Universal in 1951 and continued on most of Sirk's films from Magnificent Obsession, high points being the scores for All That Heaven Allows and Written on the Wind. Russell Gausman (set decorator) and Alexander Golitzen (set design) worked on the design and art direction for all Sirk's films after Magnificent Obsession. Both spent a considerable part of their careers with Universal, specialising in historical or fantastic decors in colour. European décor was another strong point, both working together in Max Ophuls' Letter from an Unknown Woman (1948) which has been described as “the most European film ever made in Hollywood.”

Golitzen in an interview in 1990 acknowledged that Sirk “was very conscious of the physical domain around him” and his penchant for making films “entirely within interiors ...meticulously designed...(but he) didn't interfere at all with the actual design” beyond making minor suggestions when it was submitted to him. Ross Hunter, according to Golitzen, exerted more visual control on a Sirk-Hunter film than the director” (Staggs, 223). Hunter also greatly involved himself in the wardrobe and “loved to have a white set in the picture.” Golitzen emphasised that “when the picture started shooting it was Sirk. Period.” This was confirmed by Betty Abbott Griffin, the script supervisor on many Hunter-Sirk pictures. Sirk. like John Ford, was a very economical director who shot very little excess footage. He had a productive relationship with writer George Zuckerman working with him on three adaptations, most productively on Written on the Wind and The Tarnished Angels. Sirk spoke of his preference for working with flawed or otherwise limited material for adaptation rather than fully realised novels which leave the filmmakers with “nowhere to go.”

Sirk had the benefit

of the relatively small number of stars under contract to Universal allowing

greater flexibility in casting as the studio would sign up major stars for one

or two picture contracts 'borrowing' actors for lead roles, such as, Barbara

Stanwyck for All I Desire, Stanwyck and Fred McMurray for There's

Always Tomorrow, Jack Palance for Sign of the Pagan and Lana Turner

for Imitation of Life. Rock Hudson, Jane Wyman, Robert Stack and Dorothy

Malone are the actors most identified with Sirk at Universal. Sirk first

identified Hudson's star potential but was aware of his limitations as an actor

in relation to Sirk's ongoing interest in divided characters which were best

served by Robert Stack's persona and his ability to project barely repressed

neurosis.

Take Me to

Town (1953) with Ann

Sheridan in what was, Sirk noted, “something of a farewell to cinema for

her...she had real presence...there was some sadness about her underlying the

gaiety of the part” playing a woman with a past on the run from the law. She encounters a part-time preacher and

widower (Sterling Hayden) with three young sons. Her relationship with him and

his sons is played with real warmth and naturalness by Sheridan, Hayden, and

unusually for Sirk, delightfully by the three young boys. Stern describes it as

a “melodramatic fairytale...one of Sirk's most likeable forays into nostalgic

Americana” much of it shot on outdoor sets and locations marked by “an openness

which is atypical of Sirk's work. Characters are free to recreate their lives...A

picture of Eden before the fall...Sirk's looking back at an America he once

imagined.” Robert E. Smith notes that the couple played by Hayden and Sheridan

“are able to bridge a social gap unthinkable in any other of Sirk's films in

America. Captain Lightfoot and Take Me to Town are the most

successfully lyrical of Sirk's films. He said that he had “very happy memories

of this picture” which he described as “a lyrical poem to the American

western's past.” This was the first of his films produced by Ross Hunter and

photographed by Russell Metty evident in the signature low key lighting in some

interiors. The relationship with Hunter resulted in Sirk's all-important switch

at Universal from comedies to melodrama with All I Desire the transition

film with a similar plot to Take Me to Town, the last of Sirk's 'moral

tales' set in small town America.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.