|

| Cahiers #1 |

|

| Pauline Kael |

|

| Andrew Sarris |

|

| Original Cover |

|

| Louis Skorecki (aka Jean-Louis Noames)* |

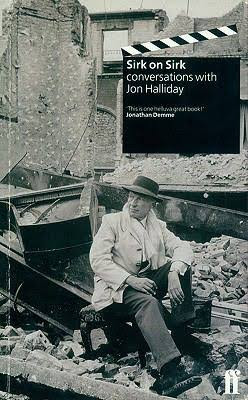

The early seventies were watershed years for film and television studies. The sixties (in the US and UK) saw the emergence of auteur structuralism which 'academised' auteurism, adapted by Peter Wollen in Signs and Meaning in the Cinema from structuralism in France . Previously film studies, mainly in the US, focused on teaching the basics of film production in the academy together with the wider institutionalised focus of film culture on 'film as art', paradigmatically art house and experimental cinema. Bordwell notes that “before 1970 most trends in film interpretation originated outside the academy.” (p 21 Making Meaning). Halliday's interview with Sirk provided a means to seriously shift the focus onto ideological issues around Hollywood films as popular culture. Here was a European intellectual who was willing and able to articulate about his knowing engagement with genre, mise en scène and ideology drawing on his experience of working successfully as a “political auteur” at the centre of Hollywood's studio system. Furthermore, his engagement was with a genre - family melodrama - that had struck a chord with cinema audiences in the fifties and early sixties but the films were either ignored or dismissed by the critical establishment as soap operas or 'woman's weepies'. Christine Gledhill has succinctly summarised that “through the discovery of Sirk a genre came into view.” A case for extending film authorship into a separate discipline of film studies anticipating literary studies by deploying post '68 continental theory (Marxism, semiotics, structuralism and psychoanalysis) was taken up to radically challenge ideological orthodoxy. What was seen to be complacent assumptions about a canon based in a humanist realism epitomised by Italian neorealism had already been bifurcated by auteurism: the relative merits of Rossellini as auteur versus those of De Sica. Screen, the magazine published by the BFI-sponsored Society for Film & Television Education (SEFT), devoted an entire issue (Summer 1971) to Sirk edited by Sam Rohdie. This was followed soon after in 1972 by a twenty film retrospective at the Edinburgh Film Festival accompanied by a booklet of essays titled Douglas Sirk edited by Halliday and Laura Mulvey.

|

| Peter Wollen |

End Note

1. In what

appears to be a typographical error in the 1968 edition of Andrew Sarris's The

American Cinema there is a significant omission in the Douglas Sirk entry (p.110)

when compared with the same entry in the first publication of Sarris's taxonomy

of 200 directors in Film Culture no 28 (1963). The part of the entry in

question (the omitted words in bold) should read: “Whereas John Stahl

transcended the lachrymose dramas of Imitation of Life and Magnificent

Obsession through the force of his naïve sincerity, Sirk

transformed the same plots into hilarious comedies (my italics)

through the incisiveness of his dark humour.”

Editor's Note: I am reminded here of my late-discovered admiration for Louis Skorecki. For many years he wrote a daily column about a movie being shown on TV that night for the left-wing French daily newspaper Liberation. My final sentence still causes much nostalgia: Winter and spring 2004. Bus rides, cinemas, bouffant hairdos, Maurice Chevalier, Mamad Haghighat, Claude-Jean Phillipe, Louis Skorecki, Paul Langevin and, once or twice, snow as we walked from the bus stop to the 7th floor apartment. You can find my memoir if you click here.

Editor's Note: I am reminded here of my late-discovered admiration for Louis Skorecki. For many years he wrote a daily column about a movie being shown on TV that night for the left-wing French daily newspaper Liberation. My final sentence still causes much nostalgia: Winter and spring 2004. Bus rides, cinemas, bouffant hairdos, Maurice Chevalier, Mamad Haghighat, Claude-Jean Phillipe, Louis Skorecki, Paul Langevin and, once or twice, snow as we walked from the bus stop to the 7th floor apartment. You can find my memoir if you click here.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.