Editor’s Note: This is the sixth part

of an expected fourteen part series about the German and American master

director Douglas Sirk (Detlef Sierck). The previous parts were published on

7th May 2017 (Sirk at Universal 1951-53)

Click on the dates to access the

earlier posts.

Bruce is a long time cinephile,

scholar and writer on cinema across a broad range of subjects. The study being

posted in parts is among the longest and most detailed ever devoted to the work

of Douglas Sirk. In the following text films in Italics are regarded as key

films in the director’s career. References to authors of other critical studies

will be listed in a bibliography which will conclude the essay.

|

| Title, The Tarnished Angels |

Two films released in 1958 - The Tarnished Angels and A Time to Love and a Time to Die - are Sirk's most personal pictures and stand apart from the 'weepies' in their fatalism, the seeming impossibility of happiness in Angels, realised only fleetingly in Time to Love. Sirk had read William Faulkner's novel Pylon in Germany and wanted to make the film there but his proposal was turned down by Ufa in 1936, its pessimism not being in tune with the demands of the Nazi regime for positive thinking. Speaking to Halliday about the attraction to him of making Pylon into a film, Sirk said he was interested in the characters and flying. Although it was a long standing project, Sirk spoke of Angels as also growing out of Written on the Wind – in their insecurities the Shumanns in Angels are extensions of the brother and sister in Wind. Sirk invoked the French word échec which means much more than failure, it also means 'no exit'; 'success' was not interesting to him. Sirk said that he was not interested in the neo-romantic idea of “the beauty of failure” and that Wind and Angels are about “an ugly, hopeless kind of failure... [as in] all the Euripidean plays.” The scriptwriter George Zuckerman, who had also written the script for Wind, was instrumental in selling it to Zugsmith “whose main interest was in the Malone part, particularly the parachute jump... Zuckerman understood that the story had to be completely 'un-Faulknerised', and it was.” Sirk was nevertheless committed to remaining faithful as possible to the spirit of the novel.

The adaptation is a desperate

attempt to translate into intelligible Hollywoodese the groping, inchoate idiom

of Faulkner's characters, their murky motivations and tortured relationships.

The film can only dramatize and over-verbalize what had been meant as a

twilight glimpse of reality sifted through the consciousness of a ruminative

and habitually drunk narrator...These limitations, however, are the medium's

limitations. They do not prevent the film from succeeding on its own terms, or

for that matter, from being by far the best screen version of a Faulkner novel.

|

| Robert Stack |

|

| Dorothy Malone, Rock Hudson |

|

| Lana Turner, Sandra Dee, Juanita Moore |

The conventions of

the 'woman's weepie' are manipulated in a melodramatic schema of American class

and race relations. Surface reality of plot and characterisation in Sirk's

melodramas, Willemen suggests, is criticised by techniques of stylisation, a

layering of the narrative through intensification of the rules of genre

developed in the theatre. Sirk said that what most engaged him about the script

of Imitation of Life was the title, adding that “there is a

marvellous saying in English, which I think expresses the essence of art, or at

least of its language, 'seeing through a glass darkly'.” Tom Ryan points out

that “imitations are everywhere in the film” with characters “adopting roles in

virtually every scene. Sirk's compositions persistently suggest the everyday as

a form of theatre... surroundings deployed as frames for performance...observing

them through doorways, against windows, in front of mirrors, on landings and

stairways, as if to underline the artifice of their exchanges.”

In the first half,

an ironic success story takes shape as Lana Turner realises her aspirations as

an actress at the price of neglecting the emotional needs of her daughter

(Sandra Dee). This merges into intensified melodrama on the theme of race and

identity given more weight as the light skinned black daughter (Susan Kohner)

rejects her mother and tries to escape inevitable racism in its multiple forms

by passing as white. Fassbinder could

recall no other film that formulates with such precision the failure of the

protagonists to see “that everything, thoughts, desires, dreams arise directly

from the social reality or are manipulated by it.” There is however a form of

apparent closure for the audience in a growing realisation that money does not

buy happiness given full expression in the moving finale, a funeral service for

the black mother in realisation of her final wishes, but Sirk intended it to be

more than a vale of tears. In the 1979 BBC interview he spoke of Annie's

emotional investment in the funeral in terms of “a demonstration of equality”

given expression in death, “Mahalia Jackson's singing a triumph...an outburst

of black power” before its political expression in the sixties. The film was a

major box office success proving to be very popular with black audiences whom

surveys showed made up a third of the audience, out of proportion to population

share. Stephen Handzo concludes that in 1959 “Imitation of Life provided

white audiences with a novel twist on a familiar soap opera plot and black

audiences (for which Susan Kohner's feelings provided a highly accurate

imitation-of-life) with a rare emotional release.” See Tom Ryan's discussion

of the Stahl and Sirk versions in Magnificent Obsession and

Imitation of Life online in Senses

of Cinema 73.

|

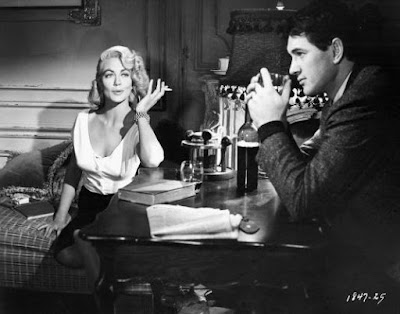

| Lil Pulver, John Gavin |

What connects Angels

and Time to Love, and separates them from Sirk's other films, is the

fatalism hanging over them. The characters cannot find happiness in Angels

because of the intrusion of the world in directly expressive terms. “In Time

to Love frames are not filled with simultaneous objects and events,

competing for our attention, images are more stark, drab and clear and hence

symptomatic of a general despair which, because of this, is less distanced than

in other Sirk films. Mirrors which recur through Sirk's work are, in Time to

Love, more integrated into the form of the whole film “as if everything is

a reflection” (Coursodon). A Time to Love is his most personal statement

about happiness expressed with great simplicity.

I was striving for this

relationship between love and ruins...Not just a boy and girl story, but two

lovers in extreme circumstances. I put a lot of myself into the love part of

the picture. It is a story close to my concerns, especially the brevity of

happiness. I am not as pessimistic as I may sometimes appear. I do believe in

happiness...happiness must be there because it can be destroyed. (Sirk on Sirk 144)

|

| Lilo Pulver |

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.