When I first saw this film at a Coolangatta cinema on Queensland’s Gold Coast in 1959, I was barely 15. As a youthful but seasoned aficionado of the western, I found it held my interest but considered it overlong and talky by the standards of John Wayne’s usual material. I certainly responded to Wayne’s casual drawl and battered hat and even more so to the sight of Dean Martin in western garb. What’s more Martin was in the centre of most of the action. I had virtually grown up on a steady diet of Martin and Lewis and the transformation came as quite a shock.

By the time Rio Bravo was doing the rounds again a decade later, I was in my phase of exploring art-house films and running the University of Queensland Film Group which I co-founded jointly with my new found friend and soul mate Roger McNiven. Roger and I were busily “educating” each other exploring all kinds of film. I introduced Roger to John Ford and he re-introduced me to Howard Hawks. I first thought he was insane when he described Rio Bravo as a western masterpiece worthy of taking its place among the greatest films ever made. It took only one screening of it, in the shed at Roger’s rented house at Kangaroo Point in Brisbane, to convince me that Roger was correct in his assessment: it became one of the major revelations of my young adult life and central to my re-assessment and understanding of mainstream Hollywood cinema.

I was still young enough and ignorant enough to be genuinely surprised that the kind of behavioural nuance and subtlety displayed in Rio Bravo was exceptional in Hollywood genre films. Surely this was exclusively the province of the arthouse circuit with its currently fashionable directors like Bergman, Truffaut, Renoir, Antonioni and other foreigners of their persuasion (or, occasionally of Ford, Welles or Hitchcock who had sometimes, and in the case of Hitchcock, almost always, set up and made films on their own terms). I began reading avidly the auteurist analyses of Cahiers Du Cinema, Robin Wood and the mob from Movie magazine instead of Sight and Sound and the local dailies.

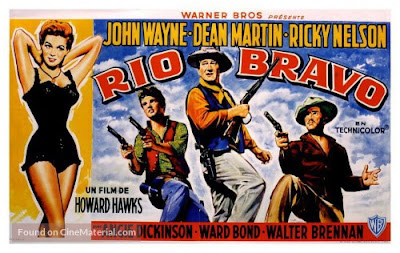

|

| French Poster |

From the present perspective, I still think Rio Bravo is a great film, one of the greatest in the Hawks canon, and certainly a quirky, individual high point of the sub-genre of town westerns. Made as a calculated response to High Noon (Fred Zinnemann, 1952) and "5.10 To Yuma" (1957) as Hawks disdainfully called the Delmer Daves film, Rio Bravo turns the situation of the Zinnemann film on its head. John Wayne as Sheriff John T Chance (T for trouble in Angie Dickinson’s words) becomes Hawks’ antidote to Gary Cooper’s Marshal Will Kane in High Noon : although both men are under severe threat against overwhelming odds from determined foes, Cooper’s response is to seek help from any source who is willing to offer it and finds none - a situation described as unbelievable and un-American by High Noon’s severest critics. Wayne on the other hand rejects all offers of aid from “well-meaning amateurs” and decides to “tough out” a siege in his own jail by a family of powerful men (led by TV’s John Russell) who are trying to bust their relative Claude Akins, a murderer, out of jail.

Wayne’s only supporters are his deputies: an “old cripple” (Walter Brennan, Stumpy, in his most substantial role for Hawks) and a drunk (Dino - in an astonishing performance that virtually re-directed his career). In the course of the film’s lengthy narrative they are joined intermittently by gambler and shady lady Angie Dickinson; a young kid (Ricky Nelson) hell-bent on revenging Wayne’s loyal friend, trail boss Ward Bond who is ambushed and murdered when he loudly offers Wayne help; and an excitable Mexican saloon-owner (Pedro Gonzales-Gonzales) dominated by his fiery wife (Estelita Rodriguez).

|

| Brennan, Wayne, Martin |

Wayne’s only supporters are his deputies: an “old cripple” (Walter Brennan, Stumpy, in his most substantial role for Hawks) and a drunk (Dino - in an astonishing performance that virtually re-directed his career). In the course of the film’s lengthy narrative they are joined intermittently by gambler and shady lady Angie Dickinson; a young kid (Ricky Nelson) hell-bent on revenging Wayne’s loyal friend, trail boss Ward Bond who is ambushed and murdered when he loudly offers Wayne help; and an excitable Mexican saloon-owner (Pedro Gonzales-Gonzales) dominated by his fiery wife (Estelita Rodriguez).

Rio Bravo is talky and leisurely (like most of Hawks’ later films) but the dialogue is chock full of Hawks’ reflections on professionalism and group dynamics. Indeed the film’s very leisureliness allows Hawks to develop his preoccupations in unusual behavioural depth. This unfolding is served by a cast which responds magnificently to the considerable demands Hawks places on them. Among the film’s many delights are a brilliant and moving experience of moral regeneration: after a particularly nasty bout of the DTs which almost has him deserting his post and scurrying back to his accustomed haunts as Borachon (town drunk), Dean Martin pours his whiskey back into the bottle (“Didn’t spill a drop”). It’s a scene that long lingers; with just a few minutes of screen time, Hawks creates something more emotionally harrowing than The Lost Weekend (Billy Wilder, 1945) in its entirety.

Hawks evolved himself into an effortlessly professional director of mainstream genre films and eventually the most laid back artist in Hollywood screen history. Rio Bravo appears to ramble along switching from frivolity to deadly seriousness while hardly seeming to change gears. It is deceptive in its density, including in its stride a quasi-Shakesperian musical interlude involving all the leading male characters; and a climactic gun battle involving dynamite, exploding buildings and extended horseplay between the film’s hero and a petulant old man that veers dangerously close to slapstick but still doesn’t depart from the expected western codes and conventions.

Most of Rio Bravo is shot indoors in confined chamber style but the behavioural detail and interaction among the characters is so strong this never for one moment becomes claustrophobic. All the players are seen to their best advantage, the screen time allowing them great scope to shape extraordinarily rounded presences, not least of all Wayne, more human and less mythic than in his work for John Ford. He is at his most endearing when he runs down the street like a herd of stampeding elephants; or when he is completely flummoxed and at the mercy of gorgeous Angie Dickinson. Her “Feathers”, incidentally with its echoes of Evelyn Brent in Sternberg’s great Underworld (1929) - is one of the film’s many delights: her legs, to Wayne’s embarrassment, are splendidly on show frequently throughout the film.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.