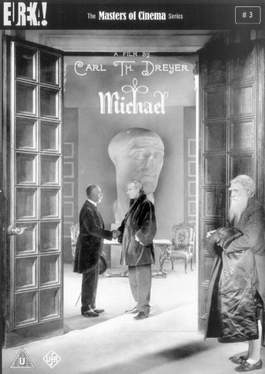

Dreyer’s

only German UFA film, Michael was

shot at Neubabelsberg in 1924, and brought him into contact with the great

cameraman Karl Freund whom he also cast in an inspired brief comic role as a

critic in the picture, together with screenwriter Thea von Harbou, who was, at

this point in history, Fritz Lang’s wife. The material for Michael comes from a novel by then openly admired gay writer Herman

Bang who was one of the pioneering figures of Weimar era gay lib in Germany

along with Magnus Hirschfeld whose 1918 picture Anders als die Anderen (Different from the Others) with Connie

Veidt was directed by Richard Oswald (Gerd’s dad) in 1918 and remains the first

groundbreaking film to deal with homosexual characters and issues. Among many

other things, Michael is in effect only the second such path-breaking film.

Bang’s novel comes from a popular genre of

tragi-romantic, sentimental writing of the period and the novel focuses on the

end of a gay romantic association. But the screenplay takes this material into

fascinating new ground by switching the tragi-Romantic era liebestod ending of

an illicit romance to a heterosexual parallel couple, in the movie the Duke du

Montheuil and another man’s wife, ending à la Schnitzler in the Duke’s death by

duel.

Dreyer’s movie opens at a point where the

sexual relationship between Michael and his patron and lover Claude Zoret (“The

Master”) is ending. The movie itself starts with a title card proclaiming “Now

I can die content, as I have known a great love”. The movie also ends with this

line, spoken by the dying Zoret, just as Dreyer’s last masterpiece Gertrud will also end with the heroine

of that film saying the same words.

So, Michael is for a start a groundbreaking

Weimar German gay film of incredible sophistication even for a society like

ours nearly a century later in which the sheer unapologetic and extremely

dignified matter-of-factness of the homosexual milieu of Zoret’s salon is a

given. Indeed, most of the movie and its characters in this artistic circle are

essentially expats to Berlin from places as far afield as Eastern Europe.

The film’s completely blithe presentation

of gayness is so embedded into the fabric of the movie even a modern day

commentator like cinephile Caspar Tybjerg cannot seem to quite bring himself to

overcome his obvious embarrassment at the films’ subject matter in a commentary

track for the 2005 MoC DVD which is carried over to the current Blu-ray

upgrade. I could live without ever again having to hear Tybjerg floundering for

some “justification” to even mention the homosexuality, as though ascribing

such “vulgarity” to a film by Dreyer might tarnish his reputation as some kind

of Sainted Exemplar of Transcendental Beatitude.

Dreyer in 1924 was already a man of the

world. And it becomes almost mandatory at this point in such a great artist's

career to note some comparability with none other than Shakespeare. Dreyer's

own small filmography includes pictures whose heart is with such central

characters as a witch, a deluded religious fanatic dying a martyr, an ageing

widow who supernaturally watches over a young married couple to guide their passage,

a neurasthenic cocaine-addicted aesthete, thrill-seeking vampires, murderous religious

crazies, a saint and halfwit witnessing a miracle, and a woman who has lived

her life alone for the sake of an undying and unfulfilled love affair.

Michael adds to this astounding role call an ageing homosexual

artist who accepts the loss of his male lover to an enterprising and glamorous

woman on the make, and who dies, like Gertrud from a broken heart, yet like

Gertrud without any regret or trace of antipathy.

Dreyer’s association with Freund, who shot

almost all the film, with Rudolf Maté coming in to finish when contractual

commitments took Freund to another job (possibly Murnau’s Die Letzte Mann/The Last

Laugh) gave Dreyer the perfect chance to enlarge his mise-en-scène,

revolutionarily indeed - thus for the first 20 minute exposition of Michael he

takes the relatively new narrative format of shot/reverse to its highest

possible level with Freund in extended decoupages of growing complexity, thus

varying shot lengths, and even more prodigiously he utilizes a plot device like

Zoret asking Michael to fetch the floodlight to illuminate the salon’s nude

painting of Michael to the Countess.

Michael’s bit of business here with the

floodlight initiates a series of shots in which the light takes its own part in

the mise-en-scène, within the cross-reverse cutting within which Dreyer and

Freund literally shift focused light from face to face, closing and opening the

image up within the frame without an iris or any other “external” device,

obliterating not only other background details but even other faces in the two

shots.

Thus the static decoupage becomes entirely

kinetic, and immensely more expressive. He also instigates a visual mode of

isolating the faces in close and two shot from the cavernous, stifling

sumptuousness of the set and background. Thus he retains an ongoing backdrop of

literal spectacle while pushing the film formally into the tighter frame and

the mood of Kammerspiel/Chamber drama. You can see Dreyer’s formal genius

literally taking off here, where he visibly engages with more and more

technical expansion.

The film at these points literally pulses

with both the excitement of visual discovery and the engagement with narrative

pacing. Early in the second act Zoret who has agreed to paint the Countess’

portrait is nearly finished but is unable to bring the eyes to life. Dreyer

sets up the sequence with the same shot/reverse decoupage as before, but with

his first shot of Michael stepping in to help, Freund instigates the film's

very first travelling into close as he dollies in to Michael approaching the

unfinished painting for which he completes the eyes. Freund dollies out when Michael

finishes and turns to face the camera and Zoret, and pulls the lighting

suddenly back out from the close facial framing to recover the set and

background into a flat wide shot of the studio. All in one shot.

Of Dreyer’s early work I've always loved The Parson’s Widow from Denmark as his

first great film and Michael always

seems to me his first masterpiece. Every other film from that point is also a

masterpiece. And at this stage of life it’s impossible not to link Michael with Gertrud as the great bookmarks of his career. Even more staggering

to me is the sheer inclusiveness and breadth of a vision of humanity that can

span from a homosexual milieu for the narrative and character setting in one

picture to a heterosexual one in the other without ever dropping a beat. There

is nobody else like Dreyer in movies. Only Mizoguchi comes close.

Some critics, notably David Cairns in his

superb 17 minute video essay on this disc go to great lengths to discuss

Dreyer’s formal immersion in the material. The new 2016 “restoration” of this

film finally gives it the astonishing visible detail, contrast, depth and

clarity it has never had before to be able to actually see in all its

magnificence Dreyer's and Freund’s genius at work. The new transfer, at its

best now faithfully presents one of the great visual masterpieces of late

silent cinema, like Sjostrom’s The Wind

and Sternberg’s last three silents at Paramount.

One of my top ten of all time.

MoC's

new Blu Ray is taken from a 2016 restoration out of Murnau Stiftung and several

other parties. The prime source used is the 35mm 2005 reprint restoration also

from FWMS, and the new 2K could have clearly benefitted even more from a large

cash injection to allow a substantial amount of photochemical work, especially

with shrinkage-related tearing, print damage and frame jumps. But what really

counts here is the literally complete illumination the new 2K brings to the

film for the first time since its premiere in 1924, along with all the clarity,

pristine resolution and visual nuance. Thus it rescues this masterpiece from

over 90 years of censorship, notoriety and neglect.

Bordwell in his extensive study "The Films of Carl -Theodor Dreyer" notes that Erich Pommel changed the film's ending without Dreyer's consent adding "that the nature of the changes remains obscure." In his analysis Bordwell comments that "all the relations are eventually subsumed by a religious one when Alice's lover dies by a cross. Similarly once Michael rejects Zoret, the film uses art objects to transform Zoret's doomed passion for his protege into a spiritual state. Worldly wealth no longer matters to Zoret..."

ReplyDeleteBruce, I can only think Erich Pommer's "changes" are indeed so obscure that Dreyer himself was unaware of them. Here is Dreyer speaking about the film, as reported in translation in Mark Nash's 1977 BFI Monograph.

ReplyDelete"For Michael I had a practically free hand. As for success this was (UFA's) fist big success in Germany. It was called the first Kammerspiel and I was very flattered by that... THe action takes place during a period when passion and exggeration were in fashion, when feelings were wilfully exacerbated; a period with a certain false manner, which is also seen in its decoration with all its outrageously supercharged interiors... Herman Bang the author belonged to the same period as Hjalmar Sjoederberg the author of Gertrud. Whether Bang imitated Sjoederberg or the other wyt around, it turns out they knew each other and were quite friendly....

I collaborated on the decors which were done by an architect.... Hugo Haring . He had never done decor for the movies bnefore this and after he never did again."

Further research into the first printed monogprah on Dreyer I have read - from then Head MOMA Curator, Eileen Bowser's 1966 monograph for MOMA's first Dreyer retro that year to coincide with the release of Gertrud in New York. Bowser duly notes the homoxsexuality of the text and then talks at length about the censorship issues including the English language release which was called "The Inverts" and after doing battle with the NY Board or Crnsors in 1926 it went on to play at what was the equlivalent of a 1920s grindhouse to successul business.

THe reading of the art/suxiality displacement is more than amply canvassed and dismissed by Mark Nash in his highly (very Brit 70s style) text based reading/semiological intertpretation. His own work is actuallyu very good on Freudian and Lacvanian analysis into manipulation of images and displacementof desire and the rest of this stuff but he never sinks to the level of making a religio-spiritual claim for Dreyer's film as working towards some baloney spiritual state. Read the movie, I says. When the movie opens the couple are no longer even living together - Zoret has set Michael up in a separate flat. As Michael is sucked into the Countess' charms and stays there even through Zoret's death, Michael starts "Stealing (it seems to us the audience) Zorets' paintings and possessions. At one point Switt, Zoret's cloose friend and diarist points all this out . Zoret replies gently to him with something beyond sanguinity. "

So what, he inherits it all anyway." Zoret's accpetance of solitude and rejection had begun before the movie began and the movie is eplxoring the path of a man who already understamds what he has gained more than what he has lost. Not often mentioned in commentary is the other great character, Switt, also gay who is obviously deeply attached to Zoret if not in fact compeltely in love with him. When Zoret dies it is Switt who is devastated and inconsolable. Michael has by now ceased to even figure in the triangle. Switt was Bang's creation in the nmovel and Dryer gives him an incredible multi layered part for anyone with eyes to see. But not perhaps David Bordwell who seems more interested in yet aagin ascribing to Dreyer some fucking sprituality of intent.

thanks David. I also have Nash which is somewhat weighted down with analytic jargon as you say. I have not seen Michael for many years but have quite a good copy a Murnau-Stiftung restoration released by Kino-International. Religiosity and spirituality to my mind are not synonymous although there is reference to religious symbolism. But i need to revisit.

DeleteYOu have to do so Bruce it's a masterpiece and tecncially what he is doing with Close up and visual manipulation very much anticipates Jeanne d'Arc. I am even tempted to think it's a greater masterpiece than Jeanne. It certainly sits there with Gertrud as the peak of his titanic work. THe older Moc PAL dvd was also the same FWMS 2005 restoration which was OK but far from ideal. The new one is using that as a basis but they have done totally new grading on the image and the clarity, blakc levels and dynamic range now are outstanding, as are resolution and definition. They need around another 100k euros to complete a really great job, I would guess. If I were filthy rich it would be the first thing I would give money to.

ReplyDelete