This is the eleventh essay in

Bruce Hodsdon’s erudite series devoted to Hollywood directors and the actors

they worked with. This essay digresses from his consideration of classical

Hollywood by focusing on one of the first, key American independents.

The previous essays can be

found if you click on the links below.

Mitchum, Monroe and Dietrich

The

Melbourne Cinemathèque is screening six films by John Cassavetes beginning on

February 28. Click on the link for details.

* * * * * * *

|

| John Cassavetes |

Cassavetes' cinema was a harbinger for the rise of

stronger and more diverse independent American cinema in the seventies which

brought with it a loosening of the system of storytelling in post classical

Hollywood. The eight feature films John Cassavetes made independently (often

financed by himself and friends) from Shadows (1959) to Love Streams (1983)

- to which should be added Gloria (1980) - have been both celebrated and

dismissed for their subjectivity that goes beyond classical norms in

establishing new sets of form and language.

Four of his films - Shadows, Faces, A Woman Under the

Influence and Gloria - connected in varying degrees with wider

audiences in a way which would have been unlikely two decades or so earlier.

When he couldn't interest any distributor in Faces, A Woman.., The Killing

of a Chinese Bookie and Opening Night he distributed them

himself; the first two set near record grosses for an 'art' movie while Chinese

Bookie and Opening Night were box office disasters. Husbands,

Minnie and Moskowitz and Love Streams were generally poorly

received by critics and audiences in America while Love Streams was a

success in Europe. Chinese Bookie and Opening Night failed to

find a theatrical audience in America at all, although the former, his only

film with tragic overtones is, with Love Streams, especially valued by

aficionados.

What follows are notes on Cassavetes' nine independently

completed features, intended to supplement the career essay by Jeremy Carr

readily accessible online if you click here from Senses of Cinema 'Great Directors' series.

|

| Lelia Goldoni, Anthony Ray, Shadows |

Cassavetes' first film Shadows (1959) began

as an improvisational exercise in his actors' workshop in NY. What becomes

clear as his filmmaking method began evolving in a second version of Shadows

with substantial scripting and reshooting, is that “improvisation” as he spoke

about it, for him had a special meaning. While always starting with a fully

developed script, he left the camera operator as free to shoot a scene as he

left the actors to discover what their character and the scene meant. He was

willing to give minor players the same room as the leads to develop their

roles. He always insisted on the hybrid nature of his art (“the emotion was

improvised. The lines were written”) and that his subject matter changed with

changes in his own life.

|

| Gena Rowlands, Faces |

The two Hollywood studio produced films which followed Shadows,

Too Late Blues(1962) and A Child is Waiting (1963)

should not be be dismissed to the extent that his biographer and advocate Ray

Carney does and, not surprisingly, Cassavetes himself also did. Following a five year gap he made a self-financed

and distributed film Faces (1968). It is centred on

a marriage crisis set against a background of life style fatigue among the

middle aged upper middle class on the west coast, materially well off but

basically passive about the crisis in their lives which dismayed him, filmed in

what are twelve master scenes, with connecting footage, on 16mm in b&w

using mainly actors he had worked with.

He said he wanted to see how people communicated with each other. Although

fully scripted he told the actors that the characters were theirs, not his, to

express as they want to.

|

| Peter Falk, Ben Gazzara, John Cassavetes, Husbands |

Cassavetes' method was to first discover the film as he

was writing it and rediscover it when rehearsing and filming. Faces is

“about people just getting by”, while Husbands (1970), in Cassavetes's

words, “is about (three) guys who want to live to find something in themselves

and others to do the same...Each moment was found as we went along without

preconceived notions of telling a predictable story.” He considered that Husbands

depicts these American males “without camouflage...no better than they are,” a

trenchant look at a certain alienation and homelessness, a contrast to the

middle class alienation represented in Faces. It clearly relates to machismo but Cassavetes

is resistant to scoring points through overt analysis. Myron Meisel writes that

“it takes common denominators of the contemporary experience and struggles to

create gestures, both behavioural and stylistic, to express Cassavetes' private

view of manners in a changing society.” It is Cassavetes' most improvised film.

He admitted he was something of a martinet on Faces but with Husbands

he was working with very experienced actors. It was the crews wanting to

follow conventional filming procedures that were often the problem.

Husbands was Cassavetes' first film

financed by a major studio (Columbia) over which he had complete control. He

threw the script away in editing the 1.5 million feet (280 hours) of film shot

over an unprecedented 23 weeks in order to leave open the option of “changing

the narrative, the relationships, the emotional through-lines and tones of

scenes as he studied the footage in the editing room to reflect what he learned

during the course of shooting the film. Cassavetes said that he set about

re-working the first version edited by Peter Tanner, presumably the assigned

editor, when Columbia executives found it entertainingly humorous. Cassavetes

edited the footage into four different versions over 12 months. It has

circulated in at least two versions, the shorter one (around 90 mins.) without

his approval.

|

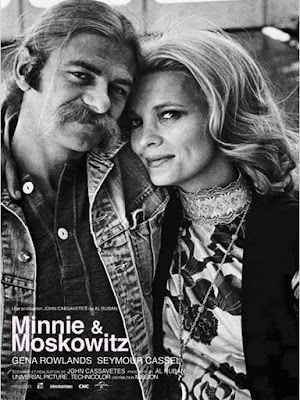

| Seymour Cassel, Gena Rowlands, Minnie and Moskowitz |

Cassavetes acknowledged that the relationship between Minnie

and Moskowitz (1971) is a veiled portrait of aspects of his

relationship with his wife Gena Rowlands. He also acknowledged his indebtedness

to Renoir's Boudu Saved from Drowning. This screwball comedy, in

which the lovers have nothing in common, was Cassavetes response to what he

felt was an aspect of American cultural programming in which individuals gave

up their individuality. He further felt that people keep private feelings too

much to themselves and should intellectualise less and rely more on feelings

(above all the power of love) in a world of pervasive loneliness and isolation

as was projected in Faces. So Minnie and Moskowitz is fantasised

as a romance taking place “in a time before intellect.” In this Cassavetes felt

intention was for the film to force viewers to open themselves to different

experiences beyond the “life as a movie” constrictions of comedy as

entertainment, in “a way of thinking that doesn't conform to lifestyles, actors

being asked to free themselves from programmed behaviours.”

|

| Peter Falk, Gena Rowlands, A Woman Under the Influence |

A shooting style fully established by A Woman Under

the Influence (1974), as described by Myron Meisel, “involves

tight focal lengths and discomfiting compositions sustaining cadenza-like

master scenes that achieve an intensity that is both theatrical and cinematic,

as in the films of Orson Welles.” The

autobiographical elements running through other of his films are particularly

strong here as noted in Jeremy Carr's essay. This is a film that thematically

could be compared with Hollywood women's melodramas like Gaslight and Home

Before Dark in which the wife's mental instability is simply the result of

her husband's machinations. But Cassavetes' film is affectively quite

different. For him, “Boudu is a woman named Mabel,” similar to Moskowitz in her

performative eccentricity. In Cassavetes' film the wife is far from being only

a victim, Nick is her opposite in his gender based dysfunction. They are tied

in the “wounded togetherness” of a working class family both committed to the

three children who in turn are attached to them.

Cassavetes said that “in replacing narrative you need an

idea. In Woman it was a concept of how much you have to pay for love.”

Gena resisted turning Mabel into a victim, or a case, or a feminist. According

to Cassavetes Gena “had a lot of consideration for the character and the woman

behind the character.” Peter Falk “an introverted closed-in man” was also left

free to interpret Nick's character. Carney said that the director always aimed

to give the actor freedom to be a person, he paid little attention to staging

of scenes for the camera, the concentration being on the actors. In speaking of

the film Cassavetes said that “all good humour comes from pain” and that he

could not make an unrealistic type of picture. Woman is open-ended but

in the writer-director's words shows “that love is possible.”

|

| Ben Gazzarra, The Killing of a Chinese Bookie |

Carney comments

that The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976) marked a

change in Cassavetes creative methods. Woman was his first film that

wasn't drawn from simple feeling. Cassavetes told Carney that it was

frightening for him “to work not out of enthusiasm but as a craftsman.” Earlier

films grew out of personal experiences. For him Chinese Bookie“was an

experiment made out of an intellectual expression of innermost feelings.” It is based on the imaginings of a self

contained world, an idea he had “tossed around” with Martin Scorsese and Sam

Shaw (producer of Woman.. and Opening Night). In Meisel's words

it “plays like a collage of Cassavetes materials...given only the superficial

trappings of a gangster melodrama, devoid of the genre's emotional thrust in

order to undercut them.” Cosmo, as played by Ben Gazzara, to Carney is “an

ordinary man defined by his work” something of an alter ego for

Cassavetes. When Gazzara told the director that he was having difficulty

understanding the character he was told that the gangsters Cosmo meets with are

reflections of the meetings Cassavetes had with studio executives, producers,

distributors and exhibitors that “in one way or another turned into double

crosses.”

What makes this and his other films often

disconcerting viewing is that for Cassavetes, Carney suggests, “truth lay in

presenting sudden surprising behaviour” rather than adhering to story lines -

an example in Bookie is the emcee Mr Sophistication (played by writer

Meade Roberts) inspired by Professor Rath in von Sternberg's The Blue Angel. The unusual dramatic strategies in Chinese

Bookie sidetrack the narrative from its thematic path- “anticlimax

without a point” as it has been described.

Adrian Martin points out that the narrative goes in multiple directions

as the voice of Cosmo returns on the soundtrack following his apparent death.

Perhaps it's his only film that can't be classified as a comedy of sorts,

having tragic overtones instead.

|

| John Cassavetes, Gena Rowlands, Opening Night |

Opening Night (1977)

The idea of doing a backstage drama went back to 1968. The film is centred on

three generations of actresses performing in a play by an aging female

playwright. The three actresses are all experiencing varying feelings of

exhaustion, doubts, even despair, about the value of their lives. Myrtle (Gena

Rowlands) is also sharing with the playwright Sarah (played by Joan Blondell but originally

written with Bette Davis in mind) her mid-life doubts. Another of the obstacles

Myrtle has to deal with to make it through to the opening night is the ghost of

a disturbed young fan killed in a car accident (an alternative take on All

About Eve) that plagues her. This becomes a metaphor in which Cassavetes

anchored Gena's own feelings about acting – “being a medium, channeling, going

into a trance, letting ghosts inhabit you.”

He didn't want audiences to easily understand Myrtle, to identify with

her. For Cassavetes “the actor is a performer whose instrument is his ego.”

Richard Combs in Sight & Sound (Summer 1978) noted Cassavetes usual lack of self consciousness

“about the layering of ironies in art imitating life, and vice versa, since the

meaning of the film is generated almost entirely by the performances.”

Cassavetes re-cut the film after the preview to make the

fate of the play more ambiguous. He saw Myrtle as the other side of Mabel in Woman

Under the Influence. She is alone and fearful of losing the sense of

vulnerability she feels she needs to be a successful actress. The enlarging of

the self through “theatricality that is in all of us,” was important to Cassavetes

-“how it can take us over.” The failure of Opening Night caused him in

frustration to condemn his filmmaking as “an expensive personal madness.” Self

financed and distributed and without an audience in America he said “it came

close to destroying our family.”

|

| Gena Rowlands, Gloria |

Although he scripted as well as directed Gloria

(1980) for Columbia , presumably without interference, Cassavetes regarded

it as an assignment and Ray Carney omits it almost entirely from serious

consideration “as among his weakest works.” It should not be so easily

dismissed. It is certainly the most integrated of his films becoming, as Meisel

puts it, “the integrated collage of movie memories and nurtured themes.” As in

his more personal films Cassavetes is in command of the consequences of style

exploring a range of options in what begins under stress as a fraught

adult-child relationship proceeding to the embrace of the bonds of profoundly

'familial' feelings played out against conventional expectations of genre

payoff. Even here he does not allow one point of view to dominate.

|

| John Cassavetes, Gena Rowlands, Love Streams |

Like A Woman Under the Influence, Love Streams (1984)

is family focussed and the most formalist in method of his later films, it is

structured around the theme of the search for love, “a continuous stream that

doesn't stop.” Cannon Films wanted an art film and Cassavetes gave them the

script of Love Streams adapted from a two hander play by his friend Ted

Allan. He said that Allan “had an enormous obsession with family loss

and pain” and that Ted was really the Robert Harmon character. They worked on

it together over four years completely rewriting the play. Cassavetes said that

Love Streams “raises troubling questions about love for which

there didn't seem to be an answer that neither I nor Ted Allan could find.” He

described it as “psychologically dangerous” - he did not know what the brother

and sister really thought of each other. Carney comments that “instead of

telling a story, scenes compared and contrasted ways of being.” Like the

majority of his films Love Streams also has strong

autobiographical elements. Cassavetes said that “Gena and I learned to be

brother and sister as the film went on.” Adrian Martin has described how

Cassavetes uses location of the home (and the club in Chinese Bookie) as

“ a generative space “ for the story, the house here more than a backdrop is

integral to generating the sense of “hallucination, reverie or madness.”

Part 2 will look at 'the Cassavetes system'.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete