|

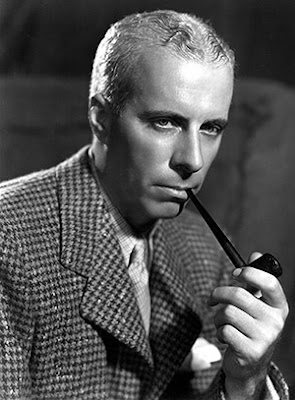

| Howard Hawks |

Hawks was an

accomplished anecdotalist who, like Ford, tended to mythologise his earlier

life and work. His youthful passion for reading fiction encouraged self-education

in storytelling techniques through intensive viewing, watching a movie that he

admired through at least two or three times. Hawks joined the story department

at Paramount in 1922. At William Fox Productions from 1923-6 he accumulated

several writing credits then directed his first film from his own story, Road

to Glory in 1926, the first of 8 silent features. From 1930-70 Hawks

directed 34 features beginning with The Dawn Patrol, also credited as

producing 20 of them, almost invariably worded in order of priority and

emphasis: “Directed and Produced by Howard Hawks.” He had sufficient status

through most of his filmmaking career to involve himself in a project from

casting through to editing, giving him a degree of control matched by few of

his peers working in the studio system.

|

| Rosalind Russell, His Girl Friday |

“I try to tell my

story as simply as possible, with the camera at eye level.” Like Ford, Hawks

did not want to give the studio bosses any other way to cut a scene and, like

Ford, he also never storyboarded; they both disliked flashbacks, unmotivated

camera movements, dissolves and hated “screwed up (camera) angles.” Yet Hawks's

images, to quote Todd McCarthy “actually are the most stylised this side of

Sternberg” reflecting his degree of construction and control of spaces and

places.

|

| Frances Farmer, Joel McRea, Come And Get It |

His collaborations

with writers constitute something of screenwriters’ who's who: Seton Miller and

William Faulkner (his two “fixer uppers”), Charles Lederer, Charles MacArthur

and Ben Hecht (on the screwball comedies), Jules Furthman (an on-going major

influence), Dudley Nichols (Air Force, The Big Sleep), Borden

Chase (Red River) and Leigh Brackett (The Big Sleep, the 'Rio

Bravo' western trilogy) whom Hawks said approvingly “writes like a man.”

Male actors

When he worked with

actors like Cagney and Bogart Hawks said that he made sure that they were “free

to try anything.” He made it clear how collaborative it was working with them,

trying different things then deciding together if they worked. “Having scenes

with good actors - Wayne and Mitchum, Bogart and Bacall – relating to each

other on the screen is always going to be better than the scripts.”

|

| John Wayne, Red River |

|

| Montgomery Clift, Red River |

|

| Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, To Have and Have Not |

|

| Dorothy Malone, Bogart, The Big Sleep |

|

| Walter Brennan (without teeth) |

Pacing

In three of Hawks's

four screwball comedies (Twentieth Century, Bringing Up Baby, His

Girl Friday and I Was a Male War Bride) the woman is aggressively

pursuing a shy man. Hawks agreed that he rather liked a relationship where the

woman is the aggressive one. Hawks's screwball comedies are based in a

dialectic opposing believability and lunacy in a love story, uniquely for

romantic comedies without any trace of sentimentality in an oeuvre notably

devoid of it, Redline 7000 (1965) perhaps being a revealing exception.

|

| Paul Muni, Ann Dvorak, Scarface |

In the Hawksian

dialectic lines of dialogue only become funny because the attitudes of the

characters are contrary to what they are trying to say. Pacing is an essential

element. In His Girl Friday (1940) they pushed the dialogue faster than

it was in The Front Page (Lewis Milestone,1931) in which it was already

fast. It was not done with editing. The dialogue was reworked, written like

real conversation which naturally overlaps, then putting extra words in the

front and end of a speech so that it was overlapped, giving a sense of speed

that doesn't actually exist, then making the actors talk a little faster. All

that was needed is for the audience to be able hear the essential things. In a

preliminary reading of the play before filming commenced, Hawks decided that it

was better to centre the comedy between a woman and a man rather than between

the two men in the original play. Ben

Hecht agreed.

Starting new

|

| Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant, Baby, Bringing Up Baby |

Hawks had a way

with launching new actresses overcome by the occasion. When a new girl was starting

a picture he had members of the crew build her confidence by prompting her to

repeat her lines to whistled appreciation. Another way was to spring surprises

if a scene was dying because a new actor was trying to play it, as when

he instructed Cary Grant without warning to empty a jug of ice water over Rita

Hayworth playing a drunk scene in her first film role. It won praise from the

critics and Harry Cohn, crucially boosting her

confidence in her debut film, Only Angels Have Wings.

|

| John Barrymore, Carole Lombard, Twentieth Century |

If at the coalface,

genre was the province of the journeyman, the measure of the auteur director in

classical Hollywood was located in the inclination and ability to orchestrate

(or as John Ford saw it, to 'predesign') the elements in both reinvigorating and

testing the constraints in storytelling conventions. Films like Bringing Up

Baby, Only Angels Have Wings and Rio Bravo are, as David

Thomson terms them, “masterpieces of the factory system” in which genre is

central. With the exception of domestic based drama (1), Hawks's intuitive

imagination was realised in at least one superior work in each individual genre

across almost the whole range in the industry within which he was more or less

content to work.

As Peter Wollen

noted, Hawks has a special place in Hollywood with the global reversibility of

genre in his oeuvre: adventure dramas have comic sub-texts while the comedies

parody the dramas. Within the films there are often mercurial shifts of mood.

What further makes them the most 'modern' to come out of classical Hollywood,

is Hawks's treatment of sexuality and gender (2). He acknowledged A Girl in

Every Port (1928) and The Big Sky (1955) as “love stories between

two men.”

An essential variant in the Hawks ethos, which he did not explore in

the earlier film with Louise Brooks, is the presence of an “honorary male” as a

single strong female in the patriarchal male group. This is made most explicit

with Jean Arthur in Only Angels Have Wings (1939). The heterosexual couple

are portrayed as equal sparring partners in the screwball comedies; Bogart and

Bacall's iconic love story is mythologised on the screen. These films remove

the traditional roles occupied by women in classical narrative, as Robin Wood,

in his 1981 second edition commentary points out, leaving them in the position

of male fantasy-figures while at the same time investing them with something of

“a fresh aliveness in their refusal to be confined in the traditional role.”

|

| Cary Grant, Jean Arthur, Only Angels Have Wings |

1. He made only one feature film in a domestic setting - Monkey

Business (1952) which Robin Wood rates as “his greatest comedy

because his most organic.” The closed groups in about ten of his other films

constitute a form of 'family'.

2. See comment on Gentlemen Prefer Blondes in Part

1 of this series.

Main Sources: Todd McCarthy Howard Hawks The Grey

Fox of Hollywood 1997; Robin Wood Howard Hawks 1968;

Jim Hillier &

Peter Woolen eds. Howard Hawks American Artist 1996; Joseph McBride Hawks

on Hawks1982; Jean-Pierre Coursodon American Directors Vol 1 1983; David Thomson The

New Biographical Dictionary of the Cinema 6th Ed. 2014; Barrett

Hodsdon The Elusive Auteur 2017; Adrian Danks “Space, Place and

Community in the Cinema of Howard Hawks” essay in Howard Hawks New

Perspectives 2016.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.