This is the latest in a fascinating series devoted to the relationships between a number of major Hollywood directors and the actors they worked with. The previous essays can be found if you click on the links below.

Ford almost always worked

closely with his writers from the beginning of the film, and over decades with

many of the same people across the spectrum from actor to editor - they knew

exactly what he wanted and collaborated in shaping a recognisably 'Fordian'

world on the screen. He had the added advantage of entering film making before

the studio system had begun to impose itself wherein the role of director

became more circumscribed as film production came to be organised along Fordist

(Henry not John) lines. This allowed Ford maximum opportunity to shape his mode

of directing which he was able to maintain even through a higher proportion of

studio assignments in the thirties. Gary Wills comments that, as the studio

system took hold, “if he could not control what he made, he would try,

at least, to control how he made it.” He also had scant regard for

institutionalised rules such as the Screen Actors Guild's imposition of

employment demarcations. Ford expected actors, for example, to change roles on

the set at his direction if they weren't immediately engaged in their acting

role.

1. In 1917 Ford directed the first of 25 silent

westerns with Harry Carey Sr, The Soul Herder, which Ford liked

to consider was his first film as director. He acknowledged Carey as his mentor

and Harry seemed to have been instrumental in persuading Carl Laemmele to

promote young Jack to director. They became estranged in later years, Ford only

casting him once as the fort commandant in The Prisoner of Shark

Island (1936). John Wayne developed a close friendship with Carey during

the war and paid tribute to him in The Searchers when, silhouetted in

the doorway, he holds the elbow of one arm with the other hand – an on-screen

gesture associated with Carey. His son Harry Jr had a long acting career,

including seven films with Ford.

Ford's personal

favourites based on his

comments to Peter Bogdanivich in what was almost certainly the longest

interview he ever gave, conducted over a seven day period in 1966: Dr Bull, Judge Priest, Stagecoach, The Grapes

of Wrath, Tobacco Road (“I enjoyed making it”), The Fugitive, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, Wagon Master, The

Sun Shines Bright (with Wagon Master and The Fugitive, “the closest to what I

wanted to achieve”).

**** **** ****

|

| John Ford, 1915 |

As verified by

Joseph McBride, John Ford was a first generation American born near Portland,

Maine in 1894 of Irish immigrant parents and named John Martin Feeney at birth.

He was the tenth of eleven siblings, five of whom died in infancy. In 1913 he arrived in a Hollywood in the

early phase of transitioning to 'Hollywood'. Ford rode with the Klan in D W

Griffith's The Birth of a Nation (1915) while at that time (1914-16) he

also acted in at least twelve 2-4 reelers directed by his brother Francis who

had adopted the name Ford as did John who was credited on films as 'Jack Ford'

until 1923.

|

| The Iron Horse |

In 1917 he wrote and directed a 2 reel western, The Tornado,

the first of 33 films under contract to Universal. Ford's first 5 reeler

(approx-imately 60 mins), his earliest surviving film, was Straight Shooting,

starring Harry Carey Sr., with a cattlemen vs homesteaders theme. He is known

to have directed more than 60 silent films of 5 reels or more between 1917-28.

His major silent, an epic western, The Iron Horse (1924), a William Fox

production, was made on a budget of $280,000 with a cast of thousands filmed

over ten months. It made Ford's name internationally. He completed his first talkie, a three

reeler, Napoleon's Barber, in 1928 with The Black Watch (1929)

being the first of 58 sound features, thirteen of them westerns. His last

feature film was 7 Women (1966). Drums Along the Mohawk (1939)

was his first film in colour. He said it was much easier for the cameraman than

black and white. Ford, Allan Dwan, Raoul Walsh and Henry King were the only

survivors from the earliest Hollywood years still directing features in the

early to mid-sixties.

In a moment of

erudition, for he was not often a cooperative interviewee, Ford told Jean Mitry,

author of the first book length study of Ford's cinema published in 1954, “that

you don't compose a film on a set. You put a predesigned composition on film.

It is wrong to liken a director to an author. He is more like an architect, if

he is creative. An architect conceives of his plan from given premises – the

purpose of his building, its size, its terrain. If he is clever he can do

something within the limitations.”

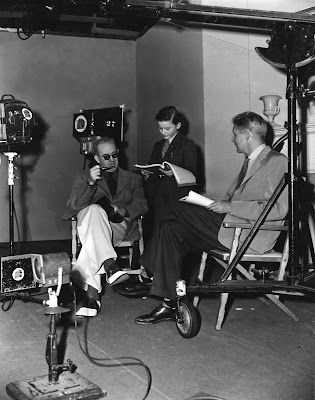

|

| Ford (l) on set |

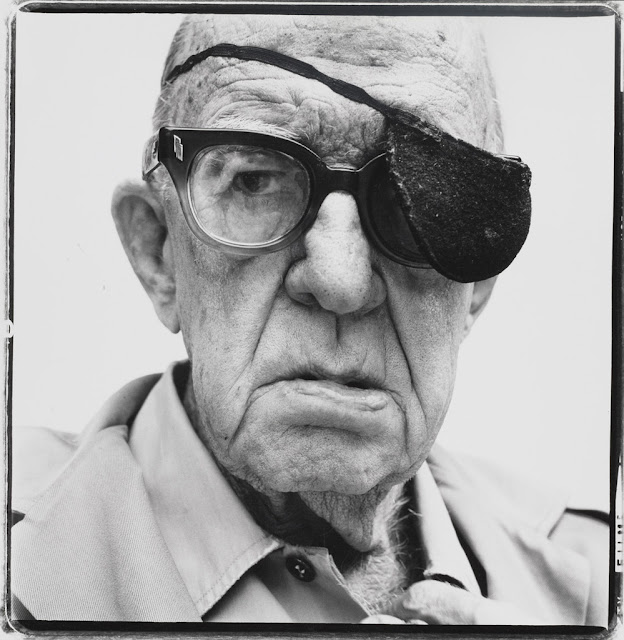

|

| Ward Bond |

He continued to

successfully set his own mode of operation throughout his long career to an

extent that was unique in Hollywood after c1930. Tag Gallagher concludes that

if working on a Ford set was “for most people a reunion, for new comers it

could be “a trial by fire” when they were singled out and given a hard time in

what amounted to a form of bullying. He

didn't only pick on newcomers but also singled out established members of the

inner circle. Often at odds with his extreme red-baiting, despite his affection

for Ward Bond, who was with Wayne his favourite actor, McBride notes that Ford,

“behaved with sadistic cruelty toward (him), making sarcastic remarks and

playing elaborate practical jokes that invariably bounced off (Bond's) 'rhinoceros-thick hide.” He was known to have reduced Victor McLaglen

and John Wayne to tears, his way, it seems, of imposing discipline on the whole

company. This said, his sets were not tense,

(bit player Danny Borzage and his accordion a frequent presence) and

Ford himself was more often “the soul of kindness” (although less so as he aged)

than unremittingly unforgiving. Many of the regulars counted their time making

Ford pictures amongst their most memorable experiences.

Andrew Sinclair in

his critical biography, observes that Ford worked more by instinct than a

standard method, profiting from the talents of actors and crew with techniques

of simplicity based on a deep knowledge of camera technology and management. A Ford

film proceeds “in a series of visual statements sparing in the use of dialogue,

rich in phrasing, simple in structure” mostly observed with a static camera,

drawing on “a language of human heritage which lay in the ritual of family –

the community, the military and the tribe” which Ford “observed with an

impatient sort of pity, a world in which moral choice meant something - he

remained a judge.”

One of his

cinematographers, Arthur Miller, said that he appeared to direct “less than any

man in the business.” He didn't want the actor “to imitate the part,” he wanted

the actor to “create the part.” He would start the morning with everyone

informally sitting around the coffee table discussing anything at random until

he suddenly interposed himself without warning, as if driven by impulse, about

something to do with the picture, addressing an actor requiring her to use her

imagination. He would then often detach himself from the conversation

temporarily lost in thought. There were never any long rehearsals, especially

of dialogue. Miller said that he never saw him “act a piece of business for an

actor” or give specific directions or set marks for the actors to position

themselves on the floor.

|

| Maureen O'Hara, Walter Pidgeon, How Green Was My Valley |

Miller, who

photographed How Green was My Valley amongst others, said that it seemed

a miracle that Ford obtained the control he did with such seemingly casual

methods, as Gallagher notes, “every scene and gesture so meaningfully

choreographed.” Henry Fonda concurred saying that Ford didn't “like to talk

about it,” that there was “practically no communication,” although he did give

actors general advice like never taking an emotion to its furthest extreme,

always leaving something for the audience to complete for themselves. Anne

Bancroft described how he arrived every morning knowing exactly what he

intended to film and “with every scene visually worked out in his mind. His

rehearsals (were) so thorough that more often than not he (would) film the most

difficult scene in one 'take'.” To Katharine Hepburn it was his sensitivity

that made him a great director of actors. This ability to almost read minds

meant Ford could prompt an actor to do what he wanted, an ability shared to

some degree by many great directors.

|

| Will Rogers, Steamboat Round the Bend |

Insofar as he was

able (studios frequently assigned lead actors to him in advance, particularly

in the thirties), Ford claimed to spend more time on casting than any other

single task. Over time he tended to build up a stock company of stars, ex-stars

and bit players. He said that a weak or even poor script can be turned into a

good picture by a good cast. Although often praised as a great storyteller, for

Ford story considerations were secondary to character, it being necessary, in

character cameos, to give a sense of “life lived” often building screen

characters on the eccentricities of individual actors. In this way his work was

done before any rehearsals which explains the results he achieved with

apparently laconic methods. He never used story boards. Both he and John Wayne

put great emphasis on naturalness, a minimising of the distance between actor

and role most epitomised by Will Rogers (who improvised many of his lines), as

well as a number of Ford's regular supporting players and John Wayne in Stagecoach

and the cavalry trilogy, for example.

In

say The Searchers (1956) or The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), for Wayne there is a greater

distance between actor and role in what amounts to an extension of his persona.

|

| "That's my steak, Liberty" Van Cleef, Marvin, Stewart, Wayne The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance |

In searching for

information on how Ford worked with actors and as a leading director in the

studio system I found there was also a darker side to his relationship with

stars such as John Wayne and Maureen O'Hara as well as a longstanding close

friend like Harry Carey Sr whose naturalistic style of acting Ford had admired

in their collaborations on the silent screen (1). Tag Gallagher who made a

sustained attempt to understand the relationship between the man and his films,

believes that no one is ever likely to write an adequate biography of him,

although Joseph McBride has since taken us much further on the journey.

Ford hid his sensitivity and erudition behind

a difficult, crusty manner and an often deliberately rough, even at times

unkempt, appearance. There seems no doubt that he was a conflicted, often

troubled man (2). He was difficult to

know or understand, essentially a loner, an alcoholic who went on benders on

his boat between films. He read voraciously and, according to Gallagher, spoke

ten languages but posed as an illiterate, frustrated by his professed inability

to write although writers with whom he collaborated like Frank Nugent spoke of

“his astonishing flair for dialogue.” He needed writing conferences as a

sounding board, Nugent noted, “sometimes groping like a musician who has a

theme but doesn't quite know how to develop it.” Ford hated expository scenes

and would brutally cut dialogue, Nugent saying that the finished film was

“always Ford's not the scriptwriter's”(3).

Gary Wills in his

book about John Wayne writes that Ford resorted to verbal humiliation, even on

occasion physical, of Wayne and other actors, often directed at those from the

stage. Like a dutiful son (the Duke called him 'pappy') Wayne just took it,

others like William Holden did not and were 'excommunicated' by Ford on the

set. Harry Carey Jr thought Wayne was frightened of Ford although Maureen

O'Hara took a somewhat different view - that she and Wayne took what Ford

dished out because of respect for his ability (4).

|

| Wayne, Stagecoach |

When the Duke was an

established star Ford embellished the beginnings of their friendship in 1926

with mythology, but it was twelve years before Ford found a major role for Wayne

in Stagecoach (1939) for which he was paid a fee substantially less than half

that of supporting actors such as Thomas Mitchell (5). Glenn Frankel reports

that while Ford and Maureen O'Hara bonded through their shared Irish heritage

and she was impressed by his competence, describing him as a magician but also

as a tyrant with an ugly streak- she was physically on the receiving end at

least once.

The paradoxes and

contradictions in Ford's personality and persona as a man and a film director -

his deliberate obscurantism and myth making about his life and relationships,

his creative rigour alternating with indulgence in his portrayal of gender

relations, sentiment and tradition, the economy in his command of visual

storytelling through the ability to edit in the camera, personalising of the

filmmaking process in which benevolent patriarch coexisted with bullying

authoritarian, his ability to create the sense of community both on the set and

in a world on the screen, his open hostility to constrictions placed on him by

producers in coexistence with his legendary position in the industry as an

unprecedented four time Oscar winner for

best director - together make John Ford classical Hollywood's most enduringly complex

creative artist.

|

| Homage to Harry Carey Snr Wayne, The Searchers |

2. When he was younger Ford had affairs

including most notably with Katharine Hepburn, the complexity of which is

discussed at length by McBride. At the end of his life Hepburn called Ford the

most fascinatingly complex man she had ever known who even did not understand

himself entirely. In later years, according to Frankel, he was not only given

to ogling young women but there were signs of repressed bisexuality as he

tended to gather handsome young men around him. O'Hara told of once walking

into his office without knocking to find him kissing a famous leading man.

3. This was Ford's preferred form of

collaboration developed in his early years directing silents, the only

exceptions being three films with Nunnally Johnson, pre-war, including The

Grapes of Wrath, and How Green was My Valley with Phillip

Dunne, which more closely followed the conventional notion of the film being

more fundamentally tied to the original script (Gallagher 464-5).

4. O'Hara also acknowledged that Ford gave her

a freedom as an actress that she otherwise never felt she had in Hollywood

which “was like being in a prison.”

5. Ford appears to have deeply resented Wayne

starring in Raoul Walsh's epic western The Big Trail (1930).

The following

are 30 Ford films of which I have a clear enough memory to rate; in bold are my

'key films'.

The thirties: The Lost Patrol, Judge Priest, The

Informer, Young Mr Lincoln, Stagecoach, Drums Along the Mohawk. The forties: The Grapes of

Wrath, How Green Was My Valley, The Long Voyage Home, They Were

Expendable, My Darling Clementine, The Fugitive, Fort Apache,

She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, Three Godfathers. The fifties: Wagon

Master, Rio Grande, The Quiet Man, The Sun Shines Bright, The Long

Gray Line, The Searchers, The Wings of Eagles, The Rising of the

Moon, The Horse Soldiers. The Sixties: Sergeant Rutledge, Two

Rode Together, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Donovan's Reef,

Cheyenne Autumn, 7 Women.

|

| Wayne, Harry Carey Jnr, Pedro Armendariz Three Godfathers |

Main Sources: Tag Gallagher. John Ford The Man and

His Films 1986. Gary Wills; John Wayne The Politics of Celebrity

1997; Andrew Sarris. The John Ford Movie Mystery 1976; Glenn Frankel. The Searchers The Making of

an American Legend 2013; Andrew Sinclair John Ford 1979; Joseph

McBride Searching for John Ford 2003; Scott Eyman John Wayne

The Life and Legend 2014; Barrett

Hodsdon The Elusive Auteur, 2016; Peter Bogdanovich John Ford

1967.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.