|

| Austerlitz |

It is only two months since I visited

Auschwitz. It was a tourist visit with

many unique aspects. Not least, our

arrival. My tour group had an appointed time to meet our guide. We were coming to Krakow and Auschwitz from

Warsaw. In the summer, northern Europe carries out its road works, and we were

getting caught up in long bottle necks on the highway, and delays of hours. I

started getting anxious – would we get there in time? And then, I’d remind myself that we were

going in comfort to a place where thousands had not wanted to get there at any

time.

With this fresh in my mind, Sergei

Loznitsa’s new film Austerlitz had a

very personal reverberance for me. It

reflects on the experience of visiting a concentration camp now that they have

become tourist attractions. The film is composed of a series of long, static,

contemplative shots looking not at gas chambers, crematoria, barracks, display

boards, but at the throngs of tourists who are looking at these. The shots are not connected in any

shot-reverse shot way, but are rather each a separate element. However, there is a degree of chronology as

the film starts with tourists arriving at one of the camps, and ends as we

watch them leave after their visit. There is no commentary, and no non-diegetic

music or sound. The only descriptions of what may be there is when we’re close

enough to hear one of the guides talking to their group.

|

| Austerlitz |

The title is not explained in the film, but

the reviewer in the Guardian noted,

The title of Sergei Loznitsa’s mysterious,

challenging, disturbing film is said by the director to be inspired by

the 2001 novel by WG Sebald, in which a character

called Austerlitz, after an upbringing in Britain as a Kindertransport refugee,

sees a Nazi propaganda film about the Theresienstadt camp and thinks that he

recognises his mother. It is a book partly about the petrification and

nullification of history created by official memorials. Of course, it has

another meaning: the title looks in the first fraction of a second like

“Auschwitz”. It is a

linguistic trompe l’oeil. The horrors of the 20th century are receding into the

dusty tomb of history, joining the battles of the 19th century: Auschwitz is a

word that may one day have as little electrical charge as Austerlitz.

The MIFF

program note mistakenly says that it was filmed at Auschwitz. Rather, it was

filmed at Dachau and Sachsenhausen,

camps near Munich and Berlin. However, I am sure the experience would be the

same at any of the camps open to today’s visitors.

This approach

takes as granted that we know about the camps.

We no longer need to be told about the showers that were gas chambers,

or the piles of hair, or glasses. It is

over sixty years since Resnais’ Night and

Fog.

Instead, we can reflect on what the experience means today, and what it

means for people visiting today.

|

| Austerlitz |

The approach leaves the audience plenty of

room to run through many thoughts, trivial and deeply philosophical. What do

you wear to go to a place where thousands were killed? Some T-shirts certainly seem inappropriate –

rather juvenile slogans ‘daring’ to use ‘fuck’. But these are probably out of

place in many places. There aren’t any priests running around covering up

women’s bare shoulders – but after all does it really matter. Very quickly a visit becomes a private thing,

not a place to show off yourself.

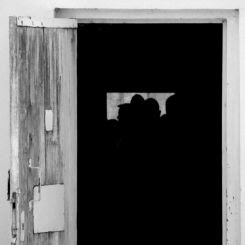

I couldn’t help noticing in fact how it did

become a private matter, even when you’re among the throngs visiting on a

lovely summer’s day. You see this is in a simple moment – one person holding a

door open for the person behind him. There is none of that eye contact we’re

used to. The door holder does this without expecting any acknowledgement of his

gesture. The person coming through is lost in their own thoughts anyway.

In fact, what are these thoughts? This is

something the film can’t communicate. There are no talking heads exploring the

experience. This is both appropriate and a limitation of the film. Perhaps it is the right approach – because it

is what such a visit means to you that is important, not what someone else made

of it.

We can be critical of some of the people at

the end turning the exit gates into an excuse for some more selfies. But

perhaps for them this is a legitimate part of their visit – a reminder that

they were able to come and go freely past gates with the notorious slogan, Arbeit Macht Frei.

Loznitsa’s film will not replace any of the

films already made on this subject, but it is a unique perspective, and repays

the time spent allowing it to provide you a space for your own reflections.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.