This week’s Fandor Criterion offerings

were a selection of films from the great Japanese director Akira Kurosawa. In

the early days of my film fandom, I made my way through IMDB’s top 250 list, which

contained number of Kurosawa films, but most of those covered there were his

samurai films. This week’s offerings were all set in the 20th century, and I

was glad to find time to catch up with three of them.

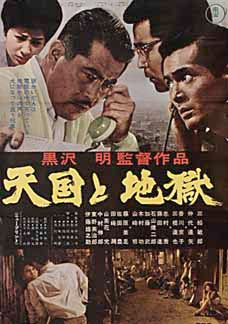

High and Low (Akira

Kurosawa, Japan, 1963) is an excellent film about a kidnapping, split neatly

down the middle. The first half focuses on the kidnapping itself, shown from

the perspective of a rich shoe company executive named Gondo, played by

Kurosawa-regular Toshiro Mifune. The kidnapper was trying to take Gondo’s son,

but after capturing the wrong child he realises he can still probably demand

ransom for the son of Gondo’s driver. The second half changes tone completely.

The film becomes a fantastic police procedural, showing the efforts of local

law enforcers as they try to locate this criminal. The logic of the search is

shown with great clarity, and the tension builds beautifully as they get closer

and closer.

Kurosawa fills both halves of the plot with

great moral complexity. He’s interested in examining why such an event would

have taken place. What about this society caused a man to take such drastic

action? The film does not forgive him, but it aims to explore him. There’s a scene

in the first half which Roger Ebert included in his list of the 100 greatest

moments in the history of cinema, where the two fathers discover the mistake,

and look at each other, realizing that with the lowered personal stakes, Gondo

could easily choose not to pay. There’s moral ambiguity in the latter scenes as

well, with the police taking a course of action which seems downright

villainous. The film skips quickly over this detail at the time, but Kurosawa

wants us to dwell on it, and to wonder whether or not we’re supposed to take

issue with it. This is great filmmaking.

The earlier film Stray Dog (Akira

Kurosawa, Japan, 1949) is another police procedural, also crafted with great

skill. Toshiro Mifune plays the lead here as well, this time as a rookie

policeman named Murakami who has his handgun stolen by a pickpocket on a

crowded bus. Murakami feels great shame at his own carelessness, which grows

much deeper when he realises his weapon is being used in a series of crimes. He

teams up with an older detective named Sato (Takashi Shimura), and the two work

their way through Tokyo’s criminal underworld in search of the thief.

Importantly, the film takes place in immediate

post-war Tokyo. The landscape is damaged, but not as damaged as the returned

soldiers. Kurosawa investigates the way the war has changed these people, for

the better or for the worse. Their actions are their own, of course, but the

situation forced upon them also takes some of the blame. The film takes place

during a heatwave, and in every scene characters are constantly mopping the

sweat away from their brows. Nobody here is ever comfortable, and that feeling helps

to raise the tension for the audience. The film’s climactic showdown is a real

highlight, showcasing the utter exhaustion suffered by both parties. It’s

another great film.

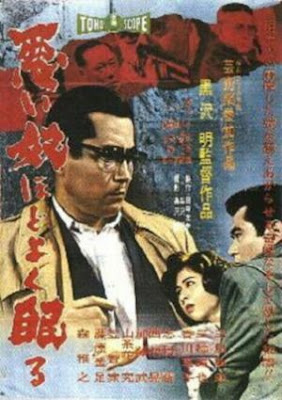

The third film I watched was another real

winner. The Bad Sleep Well (Akira Kurosawa, Japan, 1960) also takes

place in post-war Japan, with a number of important scenes taking place in a

recently-bombed factory. The themes of the week’s other two films display some

disappointment with society and hope for improvement in the future. This film

is far grimmer than that, finding only despair, and finding it in places which

make the film disappointingly relevant today.

The film opens with a scene of somewhat

clumsy exposition, as the major players and relationships are explained. In

short, the plot is about a kickback scheme between a large corporation and a

government department. Caught in the middle of this is a secretary named Nishi

(played once again by Toshiro Mifune), who has recently married the daughter of

the head of the corporation involved in the scam.

The plot becomes much denser over the

course of two and a half hours, with a bunch of faked deaths, assumed

identities and seemingly forced suicides. I make it sound vague, but there’s a

tight web of detail here, which is revealed cleverly piece by piece. It’s a

very good thriller from a masterful filmmaker, and it has a seriously powerful

ending.

With the recent announcement of Criterion’s

exclusive partnership with TCM for an upcoming streaming site (which I suspect

I will not be able to access), I’m not sure how many more weeks of Criterion

articles I’m going to get out of Fandor, but I’ll carry on as long as they’ll

let me. For now, I can tell you that next week’s article will be about sci-fi

films. I’m hoping to find a spare four hours or so to watch Rainer Werner

Fassbinder’s World on a Wire as a

part of that, but no promises on that one.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.