Nothing new came to the cinemas near me

this week, so I spent most of my time watching films from the

Criterion Collection on the streaming website Fandor

. Each week, Fandor offers a group of 7-10 films from the famous collection,

chosen to fit a theme. Each set runs for twelve days, so there are usually two

themes available at once. I watched four films from ‘The Immigrant Experience’,

and enjoyed all of them.

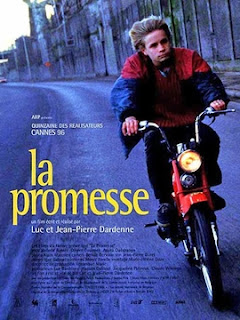

The Dardennes can always be relied upon to

tell deeply touching human stories. They examine the way real people feel, and

the choices they make within their lives. They display a belief in the inherent

goodness within people, in the willingness to make sacrifices for others. Their

films use intimate stories to highlight societal injustice, without ever

feeling like they’re preaching. All of that could be said about any one of

their films, of course, but their greatness lies in their consistency.

Le Havre (Aki

Kaurismäki, Finland/France/Germany, 2011) is another story about an illegal

African immigrant. Idrissa (Blondin Miguel), a young boy from Gabon, escapes

into the French city of Le Havre when the rest of the group he travels with are

discovered and captured. As Idrissa evades the police, he finds himself in the

care of an elderly shoe polisher called Marcel (André Wilms), who is also

caring for his sick wife Arletty (Kati Outinen). The film follows La Promesse thematically, focusing on

the idea that human beings can and will decipher the correct course of action,

even when it clashes with the law. The characters here do what they know in

their hearts they must, and we leave the film with a great sense of

satisfaction.

I’m not yet otherwise familiar with Kaurismäki’s

work, but I greatly enjoyed the tone of this film. It brings a lightheartedness

to a serious situation, without undermining the importance of the story. Marcel

and Arletty’s story in particular feels vaguely magical, especially in the way

it wraps up. There’s no reason I can see that this should work in the context

of the rest of the film, but it simply does. I look forward to seeing more from

this director.

My favourite of the three great films I saw

this week about illegal immigration was El Norte (Gregory Nava, UK/USA,

1983). The story follows siblings Rosa (Zaide Silvia Gutiérrez) and Enrique (David

Villalpando), native Guatemalans who flee from their home when the rest of

their family is captured or killed by government troops. They head north, first

to Mexico and then to the United States, seeking the fabled land of prosperity

and freedom. This long film plays out in three titled chapters, one in each of

the countries.

My favourite of the three great films I saw

this week about illegal immigration was El Norte (Gregory Nava, UK/USA,

1983). The story follows siblings Rosa (Zaide Silvia Gutiérrez) and Enrique (David

Villalpando), native Guatemalans who flee from their home when the rest of

their family is captured or killed by government troops. They head north, first

to Mexico and then to the United States, seeking the fabled land of prosperity

and freedom. This long film plays out in three titled chapters, one in each of

the countries.

The film examines the plight of refugees,

as we see the siblings unable to return home for fear of death, but unable to

live and work in the United States without constantly looking over their

shoulder for fear of discovery and deportation. They’re able to improve their

standing in life, but only as far as exploitative people will allow them to,

and always with the knowledge that it could all be stripped away from them

without notice. This film is utterly earnest. Its characters show desperation,

resilience and above all hope, no matter what life throws at them. It contains

both a wonderful journey and a crushing sense of tragedy, and it’s the best

film I saw this week.

Stromboli (Roberto

Rossellini, Italy/USA, 1950) is very different take on the immigrant

experience. Ingrid Bergman plays Karin, a Lithuanian woman who marries an

Italian fisherman (Mario Vitale) to escape from a post-war internment camp. He

tells her exciting things about the island he lives on, but fails to mention

the active volcano taking up much of its surface. Karin is unimpressed with

this. She refuses to accept the island, and its other inhabitants refuse to

accept her, so she finds herself trapped and alone in a place she hates. Her

husband is sometimes loving and supportive, sometimes brash and cruel. Bergman

spends a great deal of the film weeping.

The setting is so unique, and Bergman’s

performance so good, that they overcome some of the film’s less successful

moments. There’s one fishing scene in particular which drags on and on and on

without actually doing or saying anything, as though Rossellini thought he was

making a documentary. The feeling of alienation is overwhelming, as it must

have been for many other immigrants in post-war societies which wouldn’t

embrace them. The film surprised me with the bleakness and suddenness of its

ending, but upon reflection this is probably the best scene in the film.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.