|

| Julien Duvivier |

This means that I get to the director’s work when he is already established and assured and miss the apprentice works.

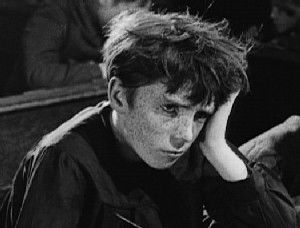

The earliest accessible Duvivier film is a first pass at the Jules Romain short stories which will become something of a signature work for the director. It’s is not altogether characteristic, though we can see his misanthropy and his envelope pushing technique. Bushy bearded Henri Krauss (a 1913 Jean Valjean) heads up the family with masculine looking shrewish mother Charlotte Barbier-Krauss, son Fabien Haziza (who cabaret tootsie Susanne Talba is vamping into stealing the family cash to take her to Paris), daughter Jean who barely figures and young freckle faced André Heuzé, called Poil de Carotte/Carrot Top, who mum mistreats. Only maid Lydia Zaréna whose heavy eye make up and lipstick don’t really jive with her simple peasant blouse and skirt, stands up for the boy despite her subservient place in the household.

The kid is delighted at the chance to go shot gun hunting with dad but mean mum forbids

it and he has to pretend disinterest to avoid her giving him a beating like the time when she’s laying into him (convincing) and sees Krauss coming to stop and ask him whether he

likes his mum or dad better. When the brother empties the cash box, mum puts suspicion

on Heuzé and it all gets to be too much. He decides the barn, the beam, the rope.

However Krauss is holding a council meeting and the board members clue him in on his wife’s mistreatment of the boy. He rushes back to grab the kid’s feet just when he kicks the support away. Embrace and explanation that he was born too late and unwanted so, though Barbier-Krauss is still his mum, from then on they will be two.

The Haute Savoie backgrounds - distant mountains, hay stacked in the fields, the fair with its merry go round, train trips, striking constructions and twenties rural community in peasant costumes, which elects Krauss as mayor, all contribute atmosphere and a few striking scenic wide shots like Heuzé’s vision of going hunting with dad Krauss in the cultivated fields.

The effects heavy style is equally conspicuous, occasionally to effect - the six Poil de Carotte’s doing the yard chores in long shot around Krauss - but the superimpositions, split screens and (curiously) shots into mirrors to produce divided image tend to distract. However I will pay the revolving mirror, that comes to a halt reflecting the brother.

A creditable effort though Duvivier did better with sound, Bauer & Lynen. The film also relates to Feyder’s remarkable Visages d’enfants (France/Swtizerland, 1925), in its child - parent relations, and the marriage game young Heuzé and Yvette Langlais play to the indignation of the girl’s mum has a hint of Les Jeux Interdits (France, 1952).

Le Tourbillon de Paris/ The Maelstrom of Paris,1928

Trashy but accomplished Duvivier silent which anticipates Au Bonheur des dames (France, 1930), as it opens with the train bringing white haired Scottish Lord Gaston Jacquet to Tiges in the Swiss Alps (very Visages d’Enfants/Mother), reading the newspaper coverage of the disappearance of Paris star Marie Duval. Jaquet finds the house where elegant Duval / Lil Dagover (Caligari, Congress Dances) enters distant. Telling cuts closer anticipate The Great Waltz. Turns out Lil’s the wife who left him because he wouldn’t let her continue her stage career.

The elderly housekeeper-mother explains she’s sick and he convinces her to go back to Scotland with him in the waiting sled. As they are about to leave, they confront her friend with black lipstick and brilliantine, Raymond Bary.

Back in London, Lil is again the toast, dancing with Bary at Claridges and feted by the diner suit critics.(“You should have left me at Tiges. There I would have been forgotten”) She resumes her stage career - scene of fittings for gowns and the necklace tried in front of one of those three face mirrors. At a reception, Bary moves on her but Jaquet has sent in his card and he comes out to tell the husband she won’t see him, only for the men to reconcile and Bary agrees to act in her interest.

Meanwhile sleazy critic René Lefèvre attempts to grope Lil and is repulsed, warning that he can turn the tide of opinion. (“I admired an artist but it was only a woman”) On opening night she imagines a well wisher accompanied by his see through derisive doppelganger - nice.

Bary has organised a derisive claque for the second act and their response makes her slump on stage, with the curtain rung down and a swarm of investors, designers and director, complete with diagonal titles, declaiming about their losses. However an aged retainer says think about her public. Bary fesses up and she goes back on and wows them. Lefevre gets his hat knocked off in the rain and Lil goes back to her Scots husband - happy end.

The soapy plot drawn from an obscure novel limits the piece but Dagover’s glamorous presence and pacing and choice of camera angles (Armand Thirard among others) are to be admired. Design and costumes, partly the work of Christian-Jacques, are particularly accomplished.

Maman Colibri/ Mother Hummingbird 1929

The team who put out Le Tourbillon de Paris had gained even more assurance when they got around to this Anna Karenina rip-off featuring the unjustly forgotten Maria Jacobini. She starred in Otzep’s The Living Corpse/Yelizaveta Andreyevna Protasova in the same year.

In the sun drenched Arab streets, Maria abandons aristocrat hunsband Jean Dax for the movies’ then-ubiquitous young lover Francis Lederer (The Wonderful Lie of Nina Petrovna, Pandora’s Box and later Midnight). Passion cools when Lederer encounters younger Lya Lys, leaving Jacobini alone. Her attempts to see the child she has been forbidden wring the hearts of the weepy audience, not to mention Court Dax.

Mounting and performance are imposing and deserve a more challenging story line.

The Algerian opening anticipates the director’s frequent North African projects and

meshes with the Joinville interiors effectively.

Au bonheur des dames 1930

Duvivier’s last silent (it was sonorised) is one of the best films of 1930, with

him and his old associates again mounting an elaborate drama around an international glamour female star - here Dita (Grand Illusion, Mlle Docteur) Parlo who was better and more attractive in her German films but still registers, particularly in her screen filling close-ups.

We kick off with a menacing shot of the smoke belching roof of a locomotive pulling into a Paris rail station disgorging Parlo in her cloche hat into churning pedestrians, complete with “Au Bonheur des Dames” sandwich board men and a line of one letter hoarding carriers, making up the name. Montage with Guido Seeber style composites and the trackings we will get through the film.

Parlo’s finds her uncle, gray haired Armand Bour’s cellar shop-home among the

demolitions, a worn beam supporting its wall. Inside unsuccessfully demonstrating the strength of the cloth in the heavy bale, he is too busy to recognise his niece. In the six months since her father’s death, when he wrote her, the big store (doubled by the real Galleries Lafayette) over the road has engulfed the rest of the district, leaving him the last hold out, living with only ill daughter Nadia Sibirskaïa and her ethnic looking live-in shop assistant fiancé. Bour blames entrepreneur manager Pierre de Guingand (Aramis from the 1921 Three Musketeers), who is prepared to run a ruinous “vendre à perte” policy to wipe out competition.

Determined to earn a living, Dita crosses the road, tracking through the milling

customers dazzled by the luxury goods. A shop lifter is hauled in by the store cop. She waits in the Staff overseer’s office and he selects her as a mannequin, taking her to thedressing room where the models laugh at Dita’s old fashioned underwear and she has to be shown how to swing her hips on the run way. At the window Dita spots model Ginette Maddie flirting with her uncle’s assistant below and tells the girl that he’s already engaged, creating tension.

The burly supervisor granny with the lorgnette is all for cutting Dita loose but manager de Guingand spots our heroine and has her hired. The mean overseer takes the credit. Both the gawky fellow employee and the boss wait for Dita after time. She looks through the window of the cellar home/shop and sees the word “bonheur” in lights opposite.

De Guingand has set himself up with the aid of powerful patroness Mme Germaine

Rouer. She introduces him to financier Baron Hartman/ Adolphe Candé, who sees De Guingand flirting with women at the reception in her presence and warns him that the way he treats women will bring him down.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.