Editor’s Note:

John C Murray died on 1 May 2019. At Adrian Martin’s suggestion I got in touch with John’s family and friends and asked them to send in their thoughts for publication on this blog. What has happened since is this spontaneous festschrift from his former friends and colleagues devoted to John C Murray’s life and work. It is a pleasure to publish it here. The internet at its finest….

|

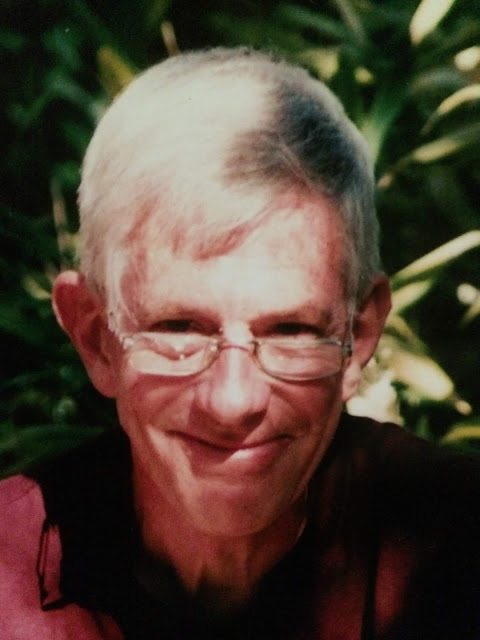

| John C Murray |

From Lee, Kristen and Steven Murray

Thank you Geoff, this was particularly welcome on the day we received notice that dad’s ashes were available for collection.

It has been a revelation for us, John’s three children, to realise how influential our father was. I suppose we just assumed that everyone’s father explained to them how Jack Clayton made the viewer know that Peter Quint was an existential menace and not a mere figment of a fragile governess’s imagination.

We greatly look forward to reading the tribute.

From Adrian Martin

I never met John face to face – I don’t believe he much frequented the burgeoning academic conference circuit of the 1980s – but I corresponded warmly with him for a time, and successfully encouraged him to return to writing about film in the early 2000s. By that period, he was mainly expressing himself on TV-related topics in newspaper pieces, thanks to commissioning editor Debi Enker. At my urging and request, John did several pieces for Senses of Cinema in its early, Bill Mousoulis-initiated days: one of his very finest essays, on Claude Sautet’s Nelly and Mr Arnaud, as well as a lovely recommendation in 2000 of “Ten Gems from the $3 Weekly Shelves ” (including Tremors, Desert Bloom and Living in Oblivion), a blast from the VHS-store past. He also did some very sharp, anonymous academic “reporting” on and assessing of submissions to issues of the academic journal Screening the Past for me. His writing and thinking, in all contexts, were precise, clear, nuanced – generous but also to-the-point where criticism and suggestion were needed.

Earlier on, back in the 1960s at the Coburg Teachers' College, John was a true pioneer of screen studies education and critical analysis in Australia, both on the intellectual and institutional levels. He made great strides in the study of audio-visual form and style (whatever the medium, film or TV), auteurs and genres, cinema and society … a large agenda that would find itself hastily reassembled (and sometimes unfairly dismissed) when the formidable legionnaires of “film theory”, 1970s-style, rode onto the field and took possession of it.

Still, during the ‘70s, John – always with a kindly eye trained upon those eager teachers in secondary schools, in country areas or other far-flung places, needing the basic but solid analytical tools to begin from – managed to write two small but important guide-books, one on cinema (Ten Lessons in Film Appreciation, 1972) and the other on TV (The Box in the Corner, 1974 – both published by long-defunct Georgian House); I donated my rare copies to Monash University when I left there in 2015. One can glimpse online, behind various university journal paywalls, John’s diverse curriculum recommendations of the ‘60s and ‘70s, when screen education was still in its earliest phases.

It might be true to say that John has been, to some extent, “left out of the history” of screen studies in Australia, but it would be fairer to state that this history has yet to be completely and comprehensively written, outside of the felt pressure to push one ideological/pedagogical barrow or another. Those who knew John and/or his work have a clearer picture of one neglected corner in this history.

John retired from teaching in March 1988 after 40 years of service. 40 years, think of that! His influence on screen education was immeasurable, and notable people who were his colleagues or students, and in some sense his protégés, included Barbara Creed, Geoff Mayer, and my good friends Freda Freiberg and Tom Ryan. I (as a teenager) first encountered John, in print, as a critic in the 1970s pages of Lumiere and Cinema Papers magazines – his brilliant, detailed, superbly written reviews were precise and instructive, but with an unmistakably Australian sensibility and wit. I well remember, for example, his review of the horror movie The Omen in Cinema Papers (no. 11, January 1977), very alive to the role of genre conventions, elements of film style, moment-to-moment inventiveness – while being, in a measured and reasonable way, critical of it at a “humanist” level. You can see the affinity there between John and the writers of Movie magazine in the UK, such as Robin Wood or Victor Perkins.

Not far into this piece on The Omen, John remarked that its “shape and development are held so firmly within generic rules that, inevitably, questions about what is going to happen next take a bad second place to an interest in how things will be shown to happen”. That style (and content) of commentary wielded a big impact and influence on me. In his VHS list for Senses, John praised a bunch of films that he felt might never “be the subject of scholarly analysis; perhaps a flash of recognition and a respectful comment en passant is the best they can hope for. Yet I find each of them to be completely satisfying in their own distinctive way. Unassuming and quietly competent, every single one does its job admirably.” There is a whole ethos of cinema, cinema-watching and cinema appreciation in those words.

John’s daughter Kristen told me: “I can safely say that I was the only kid at school who thought Jack Clayton was a genius, who had been kept up at night to watch Don’t Look Now, who saw The China Syndrome at The Capitol when they were six, and who was told, again and again, that Badlands was genius”. What better “screen education” could there be than that?

By chance, as I prepared this text for Film Alert 101, I spotted a phrase of John’s that I had quoted in a 1997 appreciation of the now-classic TV series Seinfeld: “the comedy of companionship”. A beautiful name for a televisual genre – and for a way of living. Rest in peace, John, you are a true inspiration, and you gave so many of us so much.

Adrian Martin is an Australian-born Spanish domiciled scholar, critic, writer and film and video maker. His criticism is collected at and regularly added to at his Personal Website. His latest book Mysteries of Cinema: Reflections on Film Theory, History and Culture 1982-2016 has been published by Amsterdam University Press

From Freda Freiberg

Dear Kristen,

Unfortunately I was unable to attend the service for your father, John Murray, because I was away from Melbourne at the time. I would have liked to come because John was very helpful to me and played a significant role in my professional career.

Unfortunately I was unable to attend the service for your father, John Murray, because I was away from Melbourne at the time. I would have liked to come because John was very helpful to me and played a significant role in my professional career.

I was employed at Coburg Teachers College in 1971 to teach film under John, and remained there until the middle of 1975. I learned a great deal from John, who was the major pioneer of film studies in Victoria.

From attending his lectures introducing students to film language and film criticism, I learned how to teach film appreciation. I had studied English Literature at university and taught English expression and literature

In senior high school film was not included in the academic curriculum in those days. In addition to teaching me how to teach film, John also gave me valuable advice on techniques for writing film reviews for the press.

I was offered a temporary job replacing the regular film critic of a trendy weekly paper and the prospect was exciting but I had no experience writing journalism so I turned to John for advice and he delivered in spades.

Your father was very supportive to his staff and students and a great mentor. I moved on to a successful career in academic and journalistic film criticism and in film education. I owe a great deal to John’s support and mentoring in the early years of that career.

Freda Freiberg is a long time film scholar, critic and teacher. She was a Foundation Member of the Board of the Melbourne International Film Festival.

From Tom Ryan

John was a force to be reckoned with, probably the single most inspiring influence in Australian film studies during the 1960s. Like Robin Wood in the UK, he was a pioneer in the area. Wood established his empire at Warwick University in the UK in the early 1970s, under the umbrella of the Department of Philosophy and funded by the British Film Institute. John’s emerged from inside the English Department at Coburg Teachers’ College a decade earlier, more by subterfuge than official decree because the college’s designated task was the training of primary teachers.

It’s important to note, though, that there was a key difference between the ways in which Robin and John made their presences felt. Those who came under Robin’s influence knew what they were in for from the start, or at least should have. His reputation as the author of the groundbreaking auteurist study, Hitchcock’s Films (1965), preceded him, in fact played a major part in his appointment to the university post in the first place. Those who encountered John’s inspiring lectures at Coburg (in the shadow of Her Majesty’s Prison Pentridge) had simply chosen “film appreciation” as an appealing-looking elective in their teacher training course, only to find themselves ambushed by his irresistible charisma, intellectual rigour and agile wit. And his ability to surreptitiously guide them from what they knew about films into a place where they’d never imagined they’d find themselves.

I can call them John and Robin because I was fortunate enough to study under both of them and came to share long-term friendships with them. They never met, although it was John who introduced me to Robin’s work and who wrote a wonderful piece about it for the London-based journal, Screen, entitled “Robin Wood and the Structural Critics” (Vol. 12, Issue 3, Autumn 1971, pp. 101-110). Screen’s editorial position at the time had been arrogantly dismissive of the influence which Robin (and Movie, the magazine for which he was writing) was having on the direction in which scholarly film commentary was moving, and John had managed, as it were, to infiltrate the ranks of the enemy. Because of his innovative ways, he found himself at odds every day with those of a more traditional bent, but he wasn’t taking “no” for an answer, his guerrilla-like modus operandi enhanced by his deceptively mild manner.

His approach in the lecture theatre and the seminar room was exemplary. Instead of looking down his nose at students for what they didn’t know and making them feel inferior and inadequate – an approach I’ve seen taken by more so-called teachers over the years than I care to remember – John drew creatively and compassionately on what they/we knew and built on it.

|

| Margot Kidder, The Best Damn Fiddler from Calabogie to Kaladar |

He would show films in class, drawing extensively on the lending library that had been lovingly built up by Ed Schefferle at the State Film Centre in Melbourne. They weren’t necessarily his first choices, but Coburg provided little if any budget available for hiring films (of all things) and the SFC’s collection was available for free. As a result, John’s program included a host of short films from the National Film Board of Canada: Norman McLaren’s work of course, but I also recall, in particular, a masterful 50-minute slice of social realism from director Peter Pearson, The Best Damn Fiddler from Calabogie to Kaladar (1968), starring a then-unknown Margot Kidder (in a role reminiscent of Jennifer Lawrence’s in Winter’s Bone). There were others too, including John Schlesinger’s memorable 33-minute documentary, Terminus (1961) and Lindsay Anderson’s evocative shorts, O Dreamland (1956) and Every Day Except Christmas (1957). Somehow, Schlesinger’s Billy Liar (1963) also found its way into the mix.

John’s focus was always on how we made sense of what we were seeing, urging us to think about the expectations we’d brought to it and the kinds of assumptions that were driving our thinking. He’d gently challenge us, nurturing our journeys into unknown terrains, showing us the way to deeper understandings. At the same time, he was dedicated to a bigger picture: the role that lay ahead for us, as teachers. His feelings about education in general are best summed up in the valedictory address he gave on the occasion of his retirement in 1987, and which I quote from here with the generous permission of his children, Lee, Kristen and Steven.

Recalling his early experiences of teaching a Grade 4 class at Fairfield Primary School, he reflects on the “innocent happiness” of one special day, where he found himself practising a folk dance with his class in the “otherwise deserted playground”: “Picture the scene – the warm afternoon sun, the children moving through the patterns and measures of the dance as I called the changes and clapped my hands to emphasise the beat of the music… I think that the reason why I recall (it) so vividly is that it encapsulated – rendered material – one of the great dignities of being a teacher, especially a primary teacher: that one could create the conditions for the expression and sharing of kinship, trust and communal affection – that one could make a small world for children within which, in the best sense of the phrase, they felt it was good to be alive…”

John’s special gift was that he was able to bring this kind of feeling to any classroom or lecture theatre over which he presided. During my time at Coburg, he’d discuss specific teaching strategies, inviting us to think about the ways in which we might find what worked best for us as teachers-in-training, and that was all well and good. But the thing that spoke most eloquently for him and his profession was the role model and the methodology on display whenever he was practising his glorious art as an educator.

My fellow students at Coburg were as in awe of him, and inspired by him, as I was. And his legacy is now spread throughout the land in ways that are impossible to measure but that reflect the way brilliant teachers will always leave their marks on the generations that follow.

His educational philosophy and his unabashed commitment to thinking seriously about film (and television) can also be found in his work as a commentator and a columnist (for mainstream and specialist publications) and in the three monographs he wrote: The Box in the Corner (1970), 10 Lessons in Film Appreciation (1972) and In Focus (also 1972, co-authored by his then-wife, Jan Murray). John was a wonderfully precise and often very funny writer, as concerned for the words he chose to put on the page as for the subjects with which he was dealing.

But there was more to him than his public face and I was privileged to discover parts of his private side. Early on, I was a regular visitor to the home he and Jan shared with their young family in Ivanhoe. I was even able to contribute to its décor during one of their renovations: courtesy of the manager/projectionist at the Ashril Cinema in Greensborough, the outer Melbourne suburb where I’d grown up, I was able to provide a treasure trove of old movie posters which they turned into a wallpaper collage for a study. I’m sure the value of their property multiplied many times as a result.

We both shared an interest in television as well as film. During the 1970s, I remember embarking on a project with John compiling a record of the names of TV writers and directors whom we believed were receiving insufficient attention. Working separately, we’d laboriously take down the credits, our labours eventually laying the foundations for a feature in an early issue of Cinema Papers. This was, I hasten to add, long before the arrival of computers, the Internet and IMDb.

Then there was the time he and I went together to an early screening at Melbourne’s Rapallo cinema of William A. Fraker’s Monte Walsh (1971), starring Lee Marvin and Jack Palance. Like me, John was a devotee of the Western. I always used to josh him that, had he been a foot or so taller, he could have played Marvin in a film about the actor’s life (joshing that drew a winning grin from him when I reprised it a few weeks before his death).

At the Rapallo, with only a few people in attendance, we took our seats side-by-side in a suitably isolated spot in the cinema: notebooks were at the ready, and our demeanours discouraged any distractions, or so we thought. Shortly afterwards, a young couple, for some unaccountable reason, made the extremely unwise choice of the seats directly behind us. I like to remember them as being on a first date. For a while, they sat quietly watching the film. You wouldn’t have known they were there. But then they made the mistake of opening a packet of potato crisps, which, in a further and even more serious error of judgement, they proceeded to share.

I was annoyed, of course, but I could feel John positively bristling alongside me. The bristle built and, after what was probably only a few minutes, even if it felt like a proverbial eternity, John exploded. Leaping to his feet, he spun around to face the astonished young lovers (allow me a little dramatic license, please), and exclaimed, “Jesus Christ!”

Then, the fury having passed as quickly as it had apparently arisen, he turned without any further word, resumed his seat and continued watching the film. God only knows what went through the minds of the foolhardy unfortunates on the receiving end of his counsel about cinema protocol. I suspect they had no idea what was going on or what they’d done wrong. John didn’t go on to explain that it might be better if they masticated somewhere else. Perhaps they still wake at night with John’s call for order ringing in their ears. Perhaps they’ve even been reciting their version of what happened around dinner tables for the past 48 years. Theirs, no doubt, would be a story about a crazy man with a notebook who, for no apparent reason, leapt up and yelled at them in a cinema. Whatever they thought about what had taken place, we didn’t hear another peep from them. And they were long gone by the time the credits had finished rolling.

More recently, and more sedately, John became an occasional and always delightful dinner guest, entertaining my wife, TV critic Debi Enker, with his tales about television, and sharing an enthusiasm for Buffy the Vampire Slayer with our young daughter. I think there was a time when she actually thought she was Buffy, and he did nothing to dissuade her of this notion. She says she now never thinks about her childhood heroine without also thinking about John.

To end on an even more personal note: I can’t even imagine what direction my already fortunate life would have taken without John’s influence. Courtesy of my wonderful parents, I fell in love with films at an early age. But it was John who began the process that turned that passion into a profession. His mentoring led to my introduction of film studies into the English curriculum at Watsonia High School in the early 1970s. He offered me the opportunity of filling in for him at Coburg when he took two years leave to pursue post-graduate studies. He steered me in the direction of continuing my own post-graduate studies under Robin Wood at Warwick. His inspiration was always there during my time teaching film at Melbourne State College and Swinburne University and beyond. And, from early on, he encouraged me to continue writing about film. I will always be indebted to him.

Tom Ryan is a long time teacher, critic and scholar. His latest book, The Films of Douglas Sirk: Exquisite Ironies and Magnificent Obsessions, was published this month by the University Press of Mississippi.

From Ken Mogg

A real loss. He was a marvelous head of the Film Department at Coburg State College where I found myself teaching for a while. He respected all of his staff and was a laissez-faire leader in the best way. Given that the Film Department was situated within the English Department, John was suitably knowledgeable of both his Leavis theory and his auteur theory - while (correctly) having doubts concerning the limitations of both.

He wrote two very useful books: The Box in the Corner and Ten Lessons in Film Appreciation.

I can't forget John's loping, sporty walk - nor his telling us one day that good film criticism should be like the best sports commentary (interpret that how you like). I also knew John for his stimulating role within TSEAV (Tertiary Screen Education Association of Victoria) which later became ASSA (Australian Screen Studies Association).

My debt to John is enormous, and I'm so grateful - as I am saddened by his death.

Ken Mogg is a lifetime scholar of Alfred Hitchcock's films. His recent writing on Hitchcock includes a chapter in Hitchcock and the Cold War: New Essays on the Espionage Films, 1956-1969 (ed. Walter Raubicheck), a profile of Hitchcock for Screen Education #87 (Australia), and a chapter on Hitchcock's television work for Children, Youth, and American Television (eds. Adrian Schober and Debbie Olson).

From Debi Enker

I was lucky enough to be John’s editor on a short-lived monthly film and video magazine called Freeze Framein 1987. He was our TV writer and had a column called Fine Tuning. The magazine only lasted for four issues and John wrote about Channel Seven’s long-running and incredibly long Sunday afternoon sports panel show, World of Sport, Cheers, St Elsewhere, and choice moments from a host of comedy series (MASH, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, All in the Family). After Freeze Framefolded, John also wrote occasional stories for the Gold Guide, the weekly TV, video and radio section I edited for Melbourne’s now long-gone afternoon newspaper, The Herald.

He was the sort of contributor who fretted about being up to the task, about having anything meaningful to say, and about getting his column or his story in on time. Then he invariably filed early and his words were always exquisite: thoughtful, perceptive, witty, wonderfully elegant and eloquent. His work had a fluidity and an ease that other writers could only aspire to, although I’ve been told by members of his family that the illusion of ease came from painstaking toiling over precisely how he expressed his views.

In person, he was neat and polite, almost gentle in manner. But when he got talking about TV or films, his eyes sparkled and the passion was evident.

It was a joy and a privilege to know him and to be able work with him.

Debi Enker is a longtime film and TV critic who has contributed to a wide range of publications in Australia. She writes regularly about TV for the Age and the Sydney Morning Herald, is the television columnist for the Age Green Guide and the TV critic for Jon Faine’s Morning Show on ABC Radio 774 in Melbourne.

From Geoff Mayer

Some film scholars are primarily interested in using film as a means to another end — to provide insights into culture, psychology, gender, politics, history, etc. Others, just love film. John Murray was clearly in the latter category. Many years ago, at the age of 30, I was vaguely interested in a career change after 10 years in the secondary school system. I noticed an ad from the State College of Victoria at Coburg for a senior tutor position in Film. At the time I was vice principal at a secondary school so the financial downside was great. Nevertheless, I contacted the College and spoke with John about the position — which was vacated by the departure, I think, of Freda Freiberg. John told me exactly what I wanted to hear — that this was a position to teach film — not film as literature, not film as a primary/secondary classroom tool, but film as film. I subsequently applied and worked with John for more than a decade and never regretted my decision.

As a new appointee at Coburg I monitored a number of John’s classes. As a teacher he was a revelation. Having experienced years of tired, disinterested university lecturers with ancient lecture notes and an eagerness to clear their teaching duties, John clearly wanted to teach — and it showed. He was warm, articulate and there was an impressive atmosphere of learning in his classroom. His great interest was close-analysis and to this end he gathered an impressive array of visual materials to clarify, and break up, the dialogue driven sections of the lecture — as all good teachers should.

As a writer, John functioned in the same way. Arcane theories never intruded upon, damaged or confused his clear discourse. He was always precise and analytical. John demonstrated the same qualities as the leader of an eccentric/motley collection of lecturers that included myself, Barbara Creed and many others. His sunny disposition never altered. John was always inclusive, never confrontational or divisive and an exemplary leader and colleague.

For those interested in the history of cinema/film studies in Australia, a closer examination of John’s contribution in the late 1960s and early 1970s is required. To my faltering memory, his work in establishing the foundations of the discipline predates the work at La Trobe University.

One last story, which I have mentioned elsewhere. At the first class I monitored with John, he taught one of his favourite films, the 1968 forty-nine minute award winning Canadian film The Best Damn Fiddler from Calabogie to Kaladar, featuring a very young Margot Kidder in her first feature film.John, who had assembled an impressive collection of 16 mm feature films and shorts, immediately opened my eyes to the emotional, thematic and cultural possibilities of film and The Best Damn Fiddler remains one of my favorite films — thanks to John.

Geoff Mayer is a scholar and critic currently teaching at La Trobe University. He has taught Media Studies and Film Studies in Australian and New Zealand Universities as well as secondary schools. His most recent publication isThe Encyclopaedia of American film serials

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.