It seems that the eccentric films which tell us so much about how the aesthetic field is centred, are made despite, not because of, the intrinsic character of this industry – The Screening of Australia

Australian feature films have historically interacted with international cinema on unequal terms especially after the introduction of sound. This inequality became entrenched in the postwar decades when most of the small number of critically and/or commercially successful features were made by British and American companies, in the case of the latter using Australia as little more than exotic background. From 1960-70 local filmmakers produced only 18 features (including several short features of 50-60 mins) most of which received little or no commercial release. Seven of these were 'Carlton' films (six shot on 16mm) plus two - Jack and Jill: a Postscript and Two Thousand Weeks - which were low budget by industry standards (the latter had a $90,000 budget) Melbourne based films with no direct link to the Carlton films. Both were released theatrically (with nil returns to the producers) on 35mm.

2017 marked fifty years since the first public screening of Pudding Thieves for an audience of at least two thousand at the St Kilda Palais, Melbourne in September 1967, a short feature (54 mins) more than four years in the making, mainly self funded by its writer-director Brian Davies with some assistance from the Unifed, a fund set up by the Victorian Federation of Film Societies and the Melbourne University Film Society (MUFS) to support local production with some of the profits from the Melbourne Film Festival.

There had earlier been mainly halting individual aspiration to filmmaking in the fifties linked to student film societies on university campuses in Melbourne (1) and Sydney. In the sixties, inspired in part by the French New Wave, the impetus to make films grew out of group critical practice centred on Melbourne University Film Society (2) and the availability of some support from the Unifed fund which coalesced into what I have termed 'the Carlton Ripple'.

Pudding Thieves was made at the low point of the postwar hiatus in local feature film production.

Other than the work of Charles and Elsa Chauvel (Sons of Matthew, Jedda), the most notable features made here were, as indicated, overseas productions such as several produced by Ealing Films in the UK. The Carlton Ripple at the time attracted little attention outside Melbourne, despite the absence of sustained local feature film production. The Ripple was, in its way, symptomatic of this hiatus, reflecting impatience rather than frustration with “the sad fifties,” as they has been labelled, for indigenous production of feature films.

It might be said that such local filmmaking practice, rather than celebrating place like the early films of the French New Wave, although driven by Melburnian cinephilia, as Adrian Danks has suggested “offered its own kind of cultural model (with Carlton) acting as a ghetto of film culture, connecting only sporadically with the world outside.” He describes the films produced “as a curious hybrid, definitely influenced by the French New Wave with its penchant for pastiche and quotation, but also very localised in their view of Melbourne... an avenue of 'escape' from an (apparent) moribund local culture.”

It can be said that those involved had for the most part no serious notion of generating an Oz film revival comparable to that of the Cahiers critics which also began in a cinephile culture. Yet they were inspired by the New Wave - the possibility of making commercial films with lightweight equipment on a low budget. Truffaut, Godard, Rivette, Rohmer, Chabrol et al, in varying degrees looked to the animating spirit in cinema which they called mise en scène. In Godard's words “instead of writing criticism I make a film.” Looking back on PuddingThieves in 1967 Davies saw it as “an incredible act of gall” to set out to make a feature film in this way and that “we were all genuinely surprised that the first scenes we shot looked good.”

There was a spark of wish fulfilment in Davies' observation, a glimmer of ambition for a lower budget narrative cinema (and the creative freedom that afforded) which morphed into the “Eccentric” stream of feature films in a revived Oz cinema that persisted through at least the seventies and eighties retrospectively identified in the second volume of The Screening of Australia (see note 3 below). The commentary accompanying “The Eccentrics” listing on pp 73-4 of The Screening of Australia is worth re-reading in this context. It was a notion upon which Davies himself seemed to have some second thoughts on completing Brake Fluid and one brought potentially alive by Bert Deling in Pure Shit.

Brian Davies

|

| Brian Davies, personal appearance in the final sequence of Pudding Thieves |

Davies was the acknowledged eminence grise of MUFS through the sixties, and in his writing and filmmaking - a New Wave inflected learning curve – the one most reflective.

Writing about la nouvelle vague at this time Davies saw it requiring “a greater abstraction” because of its diversity “as from all points of the French globe people were directing their first films...In the final analysis one feels the bonds which unite the film long before one knows the nature of these bonds.” In this elusive quality the only other comparable film movement up to then, Davies felt, was Italian Neo Realism. From being applied to any newcomer making a feature film in France, from the late fifties the term la nouvelle vaguewas narrowed to refer to those directors connected to Cahiers du Cinema. In the pages of Cahiers these aspiring filmmakers as critics expressed their ”irritable boredom” with much 'quality' French cinema coupled with admiration especially for genre films in American cinema.

At this time in the early sixties, of the films by frontline New Wave directors, only those by Truffaut and Chabrol had been released here. The first Godard films on Oz screens were Vivre sa vieand Bande à part during 1963-5, Breathless having been banned until the mid sixties until an English dubbed 16mm print became available from the French Embassy for non-commercial screening.

Pudding Thieves was made over four years but was largely conceived and shot in 1963-4. Although commented upon by his peers, the occurrence inthe film of a Godard-like fragmentation of the narrative line (but without using chapter headings as Godard does in Vivre sa vie), Davies felt that this was, for him, little more than fortuitous. He thought it a reflection, especially in low budget filmmaking, of the more frequent departure, such as the deployment of a hand-held camera, from formally rigid rules. At the same time, while the rawness and abruptness in New Wave films was written about, in asserting that he had not embraced the cinéma-veritéstylistics of Rouch and Rozier made possible by lightweight cameras and sound recording equipment, Davies was more in tune with Chabrol's classical approach to camera style. In Pudding Thievesa free camera was contained within a careful structuring of individual scenes.

When asked in 1962, in a three way discussion with fellow aspiring filmmakers Bert Deling and Bob Garlick, what kind of film he'd like to make Davies replied that “when I think about making films I usually think more of sequences than of whole films.” Not then lacking in ambition, he was thinking in terms of making “a comedy of manners along the lines of Smiles of a Summer Night and La Regle du Jeu...while Antonioni and the New Wave directors are the people I would study because this is the only way to learn technique... I think my style would follow that of Chabrol because he has so much command of his art, he is so dispassionate in his style and yet so enthralling at times.”

For Davies directing was a learning curve interwoven with his cinephilia and by directing plays at the La Mama Theatre in Carlton, in the spirit of the Cahiers critics making a film instead of just writing criticism. After making Pudding Thieves he directed a number of plays produced by student theatre companies, also appearing in the title role in David Williamson's first full length play The Indecent Exposure of Anthony East for the Tin Alley Players, a graduate company.

In 1967 after the completion of Pudding Thieves on a final budget of $3,500 Davies spoke of its origin in a central incident - a betrayal- which he had in mind when he started the film working forwards and backwards from this with only a bare outline of the story and two main characters, photographers dabbling in pornography. He also found some inspiration in the Colin McInnes novel Absolute Beginners which has a similar photographer as a character. “Luke's a beginner, an absolute beginner” says one of the characters in the film.

In Pudding Thieves Davies did however see the story “as just an excuse for making a film...I got interested in each scene for its own sake and wanted to make each scene look different from the others. He “wanted to see the effect of a different style, a different set of principles working in each scene.” He further wished that he had made the film more strictly and that he'd like to make a film set over two days in which the story took pride of place.

Davies said that he began Pudding Thieves determined to make a film without a single subjective shot, because of his dislike of the the ramifications of conventional structuring it carried. He did on occasions move the camera around “to create a relationship in a contrived way.”

When he was actually filming PuddingThieves Davies admitted that the he was not “worried about producing a finished gem. We were wrapped up in the activity itself...As we thought of each scene we went out and filmed it.” He agreed that the frequent humour was not intended to send up the material but was more to do with “putting on a bravura front because you're unsure of the degree of seriousness with which it will be taken.”

The intellectual impetus behind Pudding Thieves Davies saw as “a reaction to Jules and Jim and Les Cousins:the sentimental ideas about friendship.” He found that the intellectual idea “gets swallowed up by the actual experience of making the film as he got “more interested in the people who were playing the parts” until, for him, there was no difference between the actor and the character. What Davies referred to as “the tension between actor and director” may also have had something to do with the protracted time span of the film's making.

During the making of Pudding Thieves Davies made a short, Watt''s Last Voyage (1965, 9 mins). He dismissed it as “an exercise in film-making” a mistake insofar as there was strict separation of function between director, scriptwriter, cinematographer and actor (Graeme Blundell) who Davies left to his own resources something he felt as a director “you should never do.”.

He spoke less about the making of Brake Fluid (a $2000 budget entirely self funded), his more assured off-centre direction attributable to the experience of the earlier film. He had done a lot of theatre work, coming around in 1969 to the idea of making another film and felt he had more commitment to making a feature in terms of plot structure. Although the script “was modified and improvised as we went along (compared to Pudding Thieves) it has a unity of its own.” He had synch sound and a professional editor for the first time.

|

| Brian Davies filming Brake Fluid (photo: Lloyd Carrick) |

His motivation to make Brake Fluid (the title, which was briefly “the Promethean' on the script, is a red herring suggested by the playwright Jack Hibberd) was also, by his own admission, to overcome his “fear of (film) directing,” his feeling, with Pudding Thieves, that he didn't have enough commitment to the idea that he was “actually directing a feature film,” that he was “far too tentative.” He said that in making Pudding Thieves “I was frightened (I) didn't know the actors, didn't relate to them properly...I don't believe in authoritarian directors but I believe in total involvement of everybody on the job.” He thus considered that Brake Fluid was“scaled down to my world.”

Geoff Gardner the uncredited assistant producer of Brake Fluid, recalls that the New Wave films Davies viewed repeatedly in the late sixties were the innovative cinema vérité of Chronicle of a Summer (Jean Rouch & Edgar Morin 1967), and almost obsessively, Jacques Rozier's Adieu Philippine (1962) with its special sense of spontaneity in the unfolding of the narrative (both were then available for loan on 16mm from the French Embassy).

Barrett Hodsdon has suggested that Davies' films should be “better judged...not as fully realised works but for their sophisticated sense of narrative ellipses.” This is more apparent in the structuring of Brake Fluid and can be seen to be introducing into “the aesthetic force field” of Oz feature film production for the first time a “European” sophistication in structuring a narrative.

It is the “combination of the intensely local and the internationally distant,” seen by Adrian Danks as “a key characteristic of MUFS's activities in the 1960s,” that is also evident in Davies' short features,

Pudding Thieves is more about liberating the camera and narrative from seamless classicism (the 'Jules and Jim' influence); Brake Fluid made on the eve of the revival is more about freeing the narrative from cause and effect continuity while hanging onto to the threads of a unifying idea - 'boy meets girl but finds he can't talk to her' (the 'Godard' effect).

In the first decades of the revival this experimentation was more readily carried over into lower budget features mostly made in the interstices of the industry which have been termed “Interior films” in their kinship with European 'art films' concerned with 'subjectivity and inner states' and “Eccentric films” forming a more diverse grouping. (3)

In 1969 with the amount of filmmaking then going on in Carlton, Peter Carmody (Nothing Like Experience 1969) thought that it “was not just accidental but was at least partly due to LaMama “which provided actors for just about everything. Rather than the Arts Council sending Phillip Adams overseas to study film schools,” Carmody suggested, “the money would be better spent if he came to Carlton to talk to local filmmakers.” Brian Davies thought that “what was happening in Carlton was much more interesting than anywhere else in Australia in films.”

Having tentatively realised more overall structure in his second feature Davies seems to have begun to lose motivation to test this with the audience. In contrast to the time and money he invested in premiering his first feature for the public, in an interview just as he was completing the editing of Brake Fluid, he said that he was not concerned whether it was finished in time for inclusion in the Perth Film Festival. Ironically, up against the Peter Weir's more accessible Homesdale, Brake Fluid won the award for best short fiction (for films under 60 mins) at the 1971 Sydney Film Festival (4). Davies made little attempt to 'cash in' on the award and Brake Fluidsubsequently had scattered single screenings mainly around Melbourne.

Clear in his own mind that he would make no more self funded experiments on16mm, Davies had in mind films for a wider audience dismissing “the whole underground thing as self indulgent” while at the same time avoiding making a film “deliberately aimed at any particular section of the cinema going public.” It is difficult to escape the feeling that he had been primarily investing in overcoming the nouvelle vague mystique attached to film directing, almost as an end in itself. There was the challenge of reconciling his interest in experimental narrative structure and classical style if he had moved on to mainstream features with commensurately bigger budgets.

Davies did express the belief that “with improved technical facilities and the current anxiety over the lack of a domestic film industry... the time was not very far away when there'll be a place for independent filmmakers.” He said he looked at himself as “a maker of feature films... that certain conventional disciplines must be adhered to.” As possible future projects he referred to a film about Burke and Wills (“but I've already been beaten to that”- a reference to Joseph Losey's ultimately unrealised plans), a musical, a film about the Kokoda Trail and especially a film adaptation of a novel by Randolph Stow, “To the Islands.” He did not pursue funding or as far as is known approach any of the commercial production houses or producers to realise any of these projects even as government support for the industry was materialising. In 1970 Davies in effect quit filmmaking and moved to Adelaide to pursue what proved to be a successful business career.

In the 70s an offer was made to him to discuss the possibility of directing Jack Hibberd's highly successful play Dimboola but he was not interested even though many of the film's principals were old comrades from his days in student theatre and at La Mama. For Nigel Buesst “there were no special insights to be found among Davies' confidantes for this abrupt change of direction only “the implication that if one has to choose between dreams and reality you choose the latter.” (interview, Senses of Cinema no.27)

Bert Deling

Deling was anything but tentative. There is no denying that this outbreak of filmmaking in Carlton epitomised by Nigel Buesst's own substantial body of work and contributions to other people's films, remained pretty much local in scope and outreach until Bert Deling's intent to break out of the cinephiliac ghetto in search of a 'drive-in' audience. Bert, in an attack on “The Local Scene” launched in MUFS' Annotations on Film (Term 4 1963) outlined what Jacques Rivette had achieved “with a minimum of equipment and an excess of enthusiasm and talent in making his first feature Paris nous Appartient...shooting over four months on locations familiar to the principals...the cameraman and actors were personal friends and no-one was paid until the film had been sold.” The shooting script was constructed “to facilitate improvisation during filming.” Entirely post-synched it was changed considerably during dubbing to correct any weaknesses. As Bert emphasised “it could have been made in Melbourne or Sydney under conditions similar to those imposed on Rivette in Paris... shot in the spirit of 16mm production,” as Rivette described it.

In a final admonition Bert took to task “the thousands of technicians at present engaged full time in the Australian film industry (who) have not attempted their own production...a strange situation,” he proceeded to explain, by a cursory survey of the industry “populated by fifth rate Paul Rothas at their best producing at great expense, vast quantities of useless film...hopelessly inadequate for international distribution. In this age of Pennebaker, Leacock, Drew, Rouch, Marker et al.,” Deling concluded, “this is simply not good enough.”

|

| Bert Deling |

About the time Davies started filming Pudding Thieves Deling was commencing his first film with the working title Student Action which was never completed. It was funded by the University of Melbourne's Student Union and after some filming the Union simply pulled the plug on additional finance. He was actively involved, with Sascha Trikojus (who was also the cinematographer on Pudding Thieves and Deling's Dalmas a few years later) and others, in programming MUFS' screenings and editing the accompanying catalogues for a tribute to Jean Renoir (Bert's nominated “greatest director”), a Hitchcock and a combined Hawks and Ford season. He also wrote a short monograph on the career of Fellini, and essays on those of Joseph Losey, Luchino Visconti, Anthony Mann, Don Siegel, and a short comparative study of the New Wave and its impact on English language film criticism to accompany two weeks of film screenings selected to contrast the differing critical positions

If Jules and Jim was admitted to be a major influence on the footage he actually shot for his unfinished Student Action film, Dalmas (1973),filmed on 16mm in Melbourne with a budget of about $20,000 (including $10,000 grant from the newly established Experimental Film Fund), after a self-funded false start in Sydney, was more Godardian in a 'new cinema' engagement with the politics of fictional narrative. It involved abandoning the semblance of a fictional facade with a linear structure, in “a strange hybrid of Hollywood traditionalism imposed on the alternative culture” (Rod Bishop). The fiction, involving an ex-cop tracking down a drug peddling crime boss, is abruptly replaced in the second half of the film by what, in relative terms, is an 'undirected unstructured reality' of the communal experience among the group of actors. They are exploring 'being and feeling' with the aid of an hallucinogen (LSD) while in the process displacing a fictional tv crew making a doc on communal life. This relatively unstructured on-screen reality comprised of assembled reels separately shot by group members without direction from Deling then spliced together, is threatened by the potentially violent dissenting presence, as the result of an actual bad trip, by the actor who had been playing ex-cop Dalmas. Peter Whittle later admitted that his axe wielding anger was “because he thought the group needed livening up.” (Robin Laurie)

|

| Peter Cummins, Dalmas |

Instead of raising awareness of an alternative form of communicated experience, the second half of the film would seem to descend into chaotic eccentricity which is the subject of group reflection filmed six months later (see my earlier essay). The director's abdication from overall control at Lake Tyers, arising from his literal attempt to open up the film to the participation of cast and crew, is in accord with his adaptation, at that time, of Frantz Fanon's theory of the evolution of cultural identity which he more realistically scaled down into the genuinely collaborative experience of Pure Shit.

In interviews after the completion of Dalmas Deling outlined an analogous strategy for the revival of a national cinema he had adapted from Frantz Fanon's post-colonial theory of cultural identity outlined in his book The Wretched of the Earth (the film is prefaced by a quote from Fanon: “The spectator is either a traitor or a coward”). Fanon identifies three phases of evolution from a colonised to a national culture (5). Deling suggested that most Oz cinema was in the first phase (albeit with some “local colour”) - the imitation of Hollywood or BBC drama models. In implying that mainstream Oz culture was colonised by British then American culture Deling seems to overlook that in assimilating Aboriginal culture, Anglo-Celtic culture was not so analogous as 'the colonised' in Fanon's theory. Nevertheless Dalmas can be seen as a provocative questioning of the seemingly widespread assumption driving the then nascent film revival that new content (the Oz vernacular) with a little adaptation can more or less just be inserted into already received forms and genres in a 'new' national cinema.

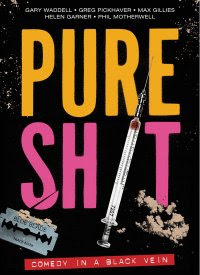

Deling aspired to locate Dalmas in Fanon's stage two in which awareness is heightened by a critiquing of the colonising process as a path to revitalising a national culture. In a modification of Fanon, Deling seems to have seen Pure Shit, as it evolved, crossing over the margin between the second and third phases - a hybrid part road movie, part screwball comedy in its immersion in a local alien sub-culture of youthful middle class drug addiction with which most of the cast was familiar. Deling in his conceptual adaptation of Fanon's third phase realisticallyplayed down the combative revolutionary aspect (although in the film savagely ridicules the methadone treatment of addiction supported by the political-medical establishment) through the artist/filmmaker 'losing' himself in a sub-culture from which vantage the middle class viewer might be galvanised out of his/her complacency.

|

| Dalmas |

Deling described both films as being very much bound by the time in which they were made. Most participating in Dalmas believed smoking dope and taking acid to be “positive and socially advantageous,”(6) in contrast to the prevailing view of those involved in Pure Shit that an opiate like heroin is a dangerous “black drug.”

The Buoyancy Foundation which provided both practical and some financial support wanted a film that would be of practical use in the rehabilitation of drug users. Buoyancy facilitated the involvement of young hard drug users in its making. The origin of the script was in a series of meetings with users over some months in which they discussed their own experiences, Deling taking notes and putting them into script form for further discussion at subsequent meetings designed to build trust and confidence in the process. On the strength of the screenplay, funding was obtained from the Film Radio & TV Board of the Australia Council.

Deling made Pure Shit for theatrical release directed particularly at a younger audience not just a film made for therapeutic purposes. He and Buoyancy were in agreement that the the didacticism of the cautionary tale, then all but mandatory in films portraying drug addiction, was to be avoided. He was intent on giving it a realistic feel that he believed could best be achieved through a departure from the conventions of naturalistic acting by rapid pacing in the delivery of speech in everyday Oz vernacular involving often overlapping dialogue. His model for this was the screwball comedy His Girl Friday which he showed to the cast and crew, further amplified in the staging and editing of the action. Pure Shit also broke new ground in the startling juxtaposition of humour with nightmarishly obsessive self destructiveness. Deling maintained to Philippa Hawker that he was “making a drive-in movie with a political message.”

When re-viewed today in the digitally restored 2009 box set, what most stands the test of time is the director's mise en scène immeasurably supported by the camerawork of Tom Cowan working fast with minimum resources and no time for any retakes, filming mostly at night with, as he notes, only a couple of banks of lights. Just as important in the scheme of things is the editing of John Scott who worked in his own time with Deling usually through the night. While he is quick to acknowledge the role of his collaborators including Buoyancy coordinator June Bryant, and Martin Armiger in the composing and arranging of the blues tinged pub rock music score, the director's guiding of the diverse cast of actors from the Pram Factory and non professionals through a high pressure three week shoot on a $30,000 budget was crucial (7). Gary Waddell in the lead is one of the stand-out performances in seventies Oz cinema as are cameos by Helen Garner as a speed freak, Phil Motherwell as a rich drug dealing coke addict and Greg Pickhaver as the man in the record store.

Deling identified Pure Shit as 'schizoid' - neither imitative of Hollywood nor committed 'to speak Australian-ness'. His courting of controversy tended to outweigh what recognition there should have been of a cinephile's brilliantly resourceful grasp of the on-screen aesthetics (mise en scène) of story-telling rare in mainstream Oz cinema (8), combined with his ability to manage the logistics from behind the camera collaboratively with cast and crew on the minimal budget.

|

| Gary Waddell (l), Pure Shit |

The funding bureaucracy, apparently uneasy about the politics of Pure Shit, refused to supply the funds for completion even on 16mm (it had to be raised by the producer Bob Weis mainly through donations it seems) which also ensured that funding was not available to produce a 35mm blow-up from the 16 negative. This would have facilitated, through film festival exposure, both domestic and overseas theatrical release. As it was the film had to wait more than two decades for something more than 'lost film' status through an archival restoration on film by the National Film & Sound Archive of Australia and digital release in a three disk package with substantial extras.

After Pure Shit Deling stated that “I'm interested in making films that are relevant to my life experience and I'm also interested in making some kind of Australian experience relevant to other Australians, particularly those that go to the commercial cinema. I'm not interested in making art films.”

|

| Australian DVD cover |

In Dead Easy (1982) career comedian Joe Martin plays Sol, a fictionalised version of Abe Saffron the legendary crime boss of Sydney's King's Cross for a good deal of the second half of last century, with Tony Barry as his rival. Scene-for-scene Dead Easy is directed with flair by Deling and strikingly lit and photographed mostly at night on location by Mike Molloy and Tom Cowan and with an atmospheric music score by William Motzing (Newsfront). Dead Easy is stylistically by no means overly bound for most of its length by genre norms but Bert may nevertheless have felt himself trapped in Fanon's phase one. Although there is a strong supporting cast of character actors the major problem is the young lead couple, caught in the middle of violent gang rivalry and police corruption, played by unknowns Scott Burgess and Rosemary Paul, who are not strong enough presences to hold the poorly structured screenplay (9) together sufficiently for the film to have been given a theatrical release in the hope of recovering a substantial budget. This, despite a car chase finale which, in its relative brevity, doesn't lose that much in the staging and editing (by John Scott) to the extended chases in Mad Max 2, for example, but only serves to deliver an anti-climactic ending. From the evidence on screen it certainly does not warrant marking the summary ending, as it does, of Deling's career as a director (10).

|

| Dead Easy |

At this distance, the New Wave seemed a vindication of how an exploratory viewing regime could have a productive bearing on filmmaking practice. The fact that the ripples with their origins in Carlton never became anything resembling waves in the film revival does not mean they were without relevance in the wayward path taken by low budget filmmaking ( “The Eccentrics” q.v.) in the wake of the emerging feature film industry powered directly and indirectly by the injection of public funds. Pure Shit, through its restoration, has assumed the role of a landmark in this history at least retrospectively producing its own ripples.

Brian Davies abandoned his self-funded ventures into filmmaking at just about the time he might have made his mark in the feature film industry. He contributed, admittedly less than he might have, leaving both the films and interviews in which he reflects on his learning curve in filmmaking – on working with actors and the relationship between style (mise en scène) and structure - which had a significant place along with the other 'Carlton films', in the then maturing context of Oz cinephilia.

This essay is a companion to my earlier essay, “The Carlton Ripple and the Australian Film Revival,” in Screening the Past no. 23 (2008). Click here for the link

Notes

1. Between 1952-4 Gil Brealey directed at least four films, with the MUFS Film Unit credited as 'producer', although three were largely self funded using some MUFS equipment. Ballade (1952 28 mins) and Royal Rag (1954 8 mins?) both appear to have survived, the latter in 'rough cut' form. 'MUFS films' Brealey is also listed as directing are The Wheel (1954 60 mins) and International House (1954), the latter with Melbourne University sponsorship, both of which appear lost. The other surviving MUFS film of this period is Le Bain Vorace (Dial P for Plughole) (1954, 8 mins) directed by Colin Munro and starring Barry Humphries. Source: Quentin Turnour Notes

2. Adrian Danks comments that “it appears that a small number of women were intermittently involved in MUFS such as Catherine Berry and Anne Barber.” Only one woman, Anne Graham, appears on the list of MUFS film productions for a short, Little Theme (1965), which is listed among the lost films. Robin Laurie was president of MUFS in the mid-sixties and collaborated with Chris Maudson on Monash 66, a documentary to assist in orienting new students (see my earlier essay referenced above). She was also a participant in Dalmas both in front of the camera and as an assistant director working with Bert on the script. Laurie later collaborated with Margot Nash on a short feminist film We Aim to Please (1976). She gives an account of her involvement in film and the theatre in Carlton and elsewhere at this link

3. See Susan Dermody & Elizabeth Jacka, The Screening of Australia Volume 2, (cover left) 1988, pp 68-74. John Duigan's first film as writer-director, the low budget (by mainstream standards) 'Carlton' film (it has affinities with Brake Fluid) shot on 16mm, The Firm Man is listed among the 'Interior' films – the world refracted through the conciousness of an alienated middle aged business executive played by Peter Cummins. Pure Shit is counted as an 'Eccentric' rather than a 'Social Realist' film as it is most often spoken of. This I think rightly recognises the innovative nature of Deling's mise en scene discussed above – the 'realistic affect' in a form of subjectivity achieved through stylisation most notably in the delivery of dialogue. Brian Davies' Pudding Thieves and Brake Fluid are not acknowledged as 'Eccentrics', where they most belong, presumably because they do not meet the industry norm as 'feature' films, running respectively 54 and 49 mins. The unique “aesthetic politics” in the structuring of Dalmas seems to have resulted in it escaping the 'Eccentric' net altogether.

3. See Susan Dermody & Elizabeth Jacka, The Screening of Australia Volume 2, (cover left) 1988, pp 68-74. John Duigan's first film as writer-director, the low budget (by mainstream standards) 'Carlton' film (it has affinities with Brake Fluid) shot on 16mm, The Firm Man is listed among the 'Interior' films – the world refracted through the conciousness of an alienated middle aged business executive played by Peter Cummins. Pure Shit is counted as an 'Eccentric' rather than a 'Social Realist' film as it is most often spoken of. This I think rightly recognises the innovative nature of Deling's mise en scene discussed above – the 'realistic affect' in a form of subjectivity achieved through stylisation most notably in the delivery of dialogue. Brian Davies' Pudding Thieves and Brake Fluid are not acknowledged as 'Eccentrics', where they most belong, presumably because they do not meet the industry norm as 'feature' films, running respectively 54 and 49 mins. The unique “aesthetic politics” in the structuring of Dalmas seems to have resulted in it escaping the 'Eccentric' net altogether.

4. It was leaked that guest of the 1971 Festival, director Jerzy Skolimowski 'intimidated' the other panel members in favour of Brake Fluid.

5. Deling's characterising of Australia as a colonised culture rather than a colonising one had more plausibility in the symptomatic hiatus in local feature film production in the fifties and sixties. For a less politically teleological model of cultural transfer see Appendix 2 below.

6. Deling found he had rapport with Richard Alpert/Ram Dass when they met while Ram Dass was visiting Melbourne in the early seventies (see also my earlier essay). This had a significant bearing on the direction Dalmas took. Alpert, as a clinical psychologist, was associated with Timothy Leary in the study of the religious use of psychedelic drugs in the early-mid sixties which became the path to Alpert's ongoing embrace of the spiritual life initially through a guru in India.

7. Reference to a $60,000 budget here, half from Buoyancy. For more background click here

8. Richard Lowenstein has acknowledged Pure Shit as an inspiration for Dogs in Space (1988). By odd coincidence the film showing on the tv set that is set alight in Dogs in Space is His Girl Friday.

9. Deling and Daniel Sankey are co-credited with the script, the latter was a Sydney solicitor who pursued Whitlam, Murphy etc, as a vendetta with initial tacit approval of the Fraser government. For more information click here

10. Bert Deling was associate producer of a sports documentary Nat Young's Fall-Line (1977). For ABC tv: as a writer on two episodes of Sweet and Sour (1984), two episodes of The Ferals (1994), also as script editor on the series in 1995 temporarily listed in the credits as “Burt Deling” and writer for episodes of The Last Resort (1988). Writer of 13 episodes of Neighbours (1999-2003) and co-writer of the story for telemovie Matthew and Son (1984). He directed one episode of Ramsay (1980). IMDb credits Deling as writer-director of a sci-fi telemovie Keiron First Voyager (1985) stated as being filmed in Sydney's “White Bay Studios” with a very sizable budget of $US 2.1m for a telemovie listed as running 62mins. Although a production still is on the database there has to be considerable doubt that Keiron was ever completed as there appears to be no record of its screening on US or Oz tv.

Appendix 1 – The Carlton Ripple in print

(See also bibliography in the link to Screening the Past provided at the head of the footnotes)

Graham Shirley and Brian Adams in Australian Cinema: the First Eighty Years (1983) devote two pages to Tim Burstall's Two Thousand Weeks (1969) the first all-Australian feature for more than a decade and“other Melbourne initiatives” referring to Melbourne filmmakers' “low budget films of urban introspection.” David Minter filmed “the cinema verité Hey Al Baby (1968) with touches of Milos Forman-style comedy also shared by Nigel Buesst's Bonjour Balwyn (1971)... In some ways a further companion piece...was Brian Davies's Brake Fluid (1970), a comedy co-written with playwright John Romeril” (who also scripted Bonjour Balwyn). Completed in 1970 after four years and only related to the Carlton films in the determination to complete a short feature on a minimal budget is “an innovative feature” by Brian Robinson and Phillip Adams, Jack and Jill: a Postscript.

Graham Shirley and Brian Adams in Australian Cinema: the First Eighty Years (1983) devote two pages to Tim Burstall's Two Thousand Weeks (1969) the first all-Australian feature for more than a decade and“other Melbourne initiatives” referring to Melbourne filmmakers' “low budget films of urban introspection.” David Minter filmed “the cinema verité Hey Al Baby (1968) with touches of Milos Forman-style comedy also shared by Nigel Buesst's Bonjour Balwyn (1971)... In some ways a further companion piece...was Brian Davies's Brake Fluid (1970), a comedy co-written with playwright John Romeril” (who also scripted Bonjour Balwyn). Completed in 1970 after four years and only related to the Carlton films in the determination to complete a short feature on a minimal budget is “an innovative feature” by Brian Robinson and Phillip Adams, Jack and Jill: a Postscript.

In The Last New Wave: the Australian Film Revival (1980) David Stratton has a chapter headed “Carlton Cinema.” After a brief introduction in which he lists the Carlton filmmakers it is devoted to the career of John Duigan, his first four features as writer-director with the next four, to 1987, in Stratton's companion book The Avocado Plantation. Duigan is a writer-director with more than twenty features to his credit (including 10 in the US or UK) from The Firm Man (1974), a 'Carlton film' a black comedy made on a $15,000 budget, to Careless Love (2012) his first film in Oz for 15 years. After the venture into surreal narrative in his first feature, Duigan was already describing himself as a politically focused filmmaker who recognises that the message is best perceived through the power to move and entertain. His Oz films also include Mouth to Mouth (1978), Winter of Our Dreams (1981), Far East (1982), the semi-autobiographical AFI award-winners The Year My Voice Broke (1987) and its sequel Flirting (1991). This second career in film followed his initial involvement in Bonjour Balwyn and Brake Fluid as the lead actor “without dreaming of making a film myself.” He saw himself as primarily an actor and writer who had published a novel Badge. He also appears in Dalmas as the director of a tv crew making a documentary on communal living. His interest in directing developed through the desire to reach a wider audience while with what he described as “a kaleidoscopic” travelling theatre group touring Gippsland and the NSW South Coast in the early seventies. Interview with John Duigan in Sue Matthews Interviews with Five Directors 1984

The chapter of The Last New Wave headed “Poor Cinema” includes a section -The Melbourne Scene- a further discussion of the Carlton films from the mid sixties to the mid seventies and Deling's Dalmas and Pure Shit,with the The Sydney Scene including Albie Thoms and Ubu Films.

The Oxford Companion to Australian Film (1999) has entries for Nigel Buesst, Bert Deling and Pure Shit as well as for Carlton film pioneer Giorgio Mangiamele and his feature Clay (1965) but mentions Brian Davies and his two short features only in passing in the entries on Deling and Buesst. There is an entry on John Duigan and separate entries for seven of his first ten features as director up to and including Flirting (1991).

The Oxford Companion to Australian Film (1999) has entries for Nigel Buesst, Bert Deling and Pure Shit as well as for Carlton film pioneer Giorgio Mangiamele and his feature Clay (1965) but mentions Brian Davies and his two short features only in passing in the entries on Deling and Buesst. There is an entry on John Duigan and separate entries for seven of his first ten features as director up to and including Flirting (1991).

Three references to film production in the context of MUFS's history:

Adrian Danks, “Arrested Development or from The Heroes are Tired to The Tomb of Ligeia: Some Notes on the place of Melbourne University Film Society in 1960s Film Culture, Go! Melbourne in the Sixties Eds. Seamus O'Hanlon and Tanja Lake 2005.

Quentin Turnour, “Notes Towards a History of MUFS Film Production,” in There is more to films than the Goldwyn Girls know, catalogue accompanying an exhibition celebrating 50 years of MUFS, eds. Turnour and Windsor Fick, 1999.

Barrett Hodsdon, Straight Roads and Crossed Lines:the quest for Film Culture in Australia?2001. From pp. 62-88 the University film societies (primarily MUFS and Sydney University Film Group) are discussed in terms of the new critical axis in the sixties and with what are termed the “film production gestures” based on both campuses discussed on pp. 62-5.

Brian Davies sources.

“Film Production at the University” a conversation between Davies, Deling and Bob Garlick in MUFS' Annotations on Film Term 3 1962. For Pudding Thieves an interview with Davies in Annotations on Film Terms 3&4 1966 and University Film Group Bulletin 6 1967. In the same issue of UFGBulletin Geoffrey Gardner concludes a review of Pudding Thieves :

Within the causality, the rawness, the unexpected humour, the

emphasis on the momentary, we can sense the rediscovery of

of film basics. Davies, like the New Wave, offers a return to

the simplicity and lack of cunning (in the sense of lack of ef-

fect and deliberate impact) that characterizes the brothers Lu-

miere.

For Brake Fluid: interviews inCinema Papers (series 1) issue 5 Feb 1970 and Annotations Term 2 1970. Davies wrote on La Nouvelle Vague in Annotationsterm 3 1962 and Term 1 1969.

Bert Deling sources.

For Dalmas a review by Rod Bishop together with an interview with Deling by Bishop and Fiona Mackie in Lumiere 22 1973. The best retrospective sources for Pure Shit are articles by John Conomos in Cinema Papers 101 1994, Megan Spencer in 100 Greatest Films of Australian Cinema 2006, Adrian Danks in Metro no 149 2006 and Philippa Hawker in Metro 165. Interviews with Bert Deling in Filmnews Feb 1977, Cinema Papers 12 1977, and an interview with Deling included as an extra in the 2009 dvd release of Pure Shit. Other dvd extras include commentaries accompanying the film by Deling and producer Bob Weis, and by actors Gary Waddell and John Laurie. Among the other interviewees in the package are the cinematographer Tom Cowan, editor John Scott and composer Martin Armiger.

See also “The Alternate Canon of Great Australian Films” in Pure Shit Australian Cinema, a 2009 Interview with Bert Deling and reviews of Pure Shit by Luke Buckmaster and Peter Galvin (both 2009).

See also “The Alternate Canon of Great Australian Films” in Pure Shit Australian Cinema, a 2009 Interview with Bert Deling and reviews of Pure Shit by Luke Buckmaster and Peter Galvin (both 2009).

Davies wrote an article about Phillipe de Broca for Film Journal 22, 1963. Geoff Gardner comments that “we were so deprived of the New Wave films in the early 60s that the joie de vivre of de Broca's elegant little sex farces seemed to stand-in for generic 'New Wave' films.”

Appendix 2: A Five Stage Model of Cultural Transfers

Tom O'Regan in Australian National Cinema (1996) draws attention to the role of cultural transfers in the formation of cultures. It offers a more complex model of cultural transfer. O'Regan's intention is to take us beyond simple import/export, unoriginal/original dichotomies and cultural imperialism rhetoric. In this he finds the work of semiotician Yori Lotman particularly useful in proposing a five stage model of cultural transfers within the general context of a culture which cannot turn itself into a sending culture without first becoming a receiving one. In the first stage the imported text from say Hollywood, British quality or European art cinemas 'keep their strangeness' and are valued ('read and accepted') for this more than those of the home culture. A second stage is 'when the imported text and the home culture...structure each other' as in the case of the updating of Casablanca in Far East. A more debatable example is Scott Murray's Devil in the Flesh (1989)set in Australia during WWII but adapted from the 1923 French novel Le Diable au Corpsfirst filmed in France in1947, is quoted by O'Regan as,'a remake that influenced the subsequent French remake'. Bad Boy Bubby 'indigenizes' the Eastern European art film'. In the third stage a 'higher content' - 'a world view' - in the imported text is separated from its national culture and attached to the local content, examples being Mad Max and Newsfront which can in the process be seen to improve on their Hollywood and quality film exemplars.The fourth stage – the Mad Max trilogy, along with Shame, Neighbours and The Dismissal - are examples where asymmetrical invasions from the outside are transformed by the dissolving of the imported text into a new structural model while 'perhaps (providing) original structural models for their genres...with international consequences' as Australian soaps, for example, can be seen as objects in their own right. But for the failure of the AFC assessors there was potential for Pure Shit tohave filled this role. In the fifth stage the receiving culture assumes, in a limited form, the Hollywood paradigm of a general transmitting culture. In Australian cinema this is only achieved with individual films and tv series -fromThe Piano, Babe, or Happy Feet, to Oz imitations like Harlequin and Roadgames or to differing forms of adaptation in Mad Max or Neighbours.These can run the risk of attracting criticism on the home front for 'selling out' Australian specificity.

Tom O'Regan in Australian National Cinema (1996) draws attention to the role of cultural transfers in the formation of cultures. It offers a more complex model of cultural transfer. O'Regan's intention is to take us beyond simple import/export, unoriginal/original dichotomies and cultural imperialism rhetoric. In this he finds the work of semiotician Yori Lotman particularly useful in proposing a five stage model of cultural transfers within the general context of a culture which cannot turn itself into a sending culture without first becoming a receiving one. In the first stage the imported text from say Hollywood, British quality or European art cinemas 'keep their strangeness' and are valued ('read and accepted') for this more than those of the home culture. A second stage is 'when the imported text and the home culture...structure each other' as in the case of the updating of Casablanca in Far East. A more debatable example is Scott Murray's Devil in the Flesh (1989)set in Australia during WWII but adapted from the 1923 French novel Le Diable au Corpsfirst filmed in France in1947, is quoted by O'Regan as,'a remake that influenced the subsequent French remake'. Bad Boy Bubby 'indigenizes' the Eastern European art film'. In the third stage a 'higher content' - 'a world view' - in the imported text is separated from its national culture and attached to the local content, examples being Mad Max and Newsfront which can in the process be seen to improve on their Hollywood and quality film exemplars.The fourth stage – the Mad Max trilogy, along with Shame, Neighbours and The Dismissal - are examples where asymmetrical invasions from the outside are transformed by the dissolving of the imported text into a new structural model while 'perhaps (providing) original structural models for their genres...with international consequences' as Australian soaps, for example, can be seen as objects in their own right. But for the failure of the AFC assessors there was potential for Pure Shit tohave filled this role. In the fifth stage the receiving culture assumes, in a limited form, the Hollywood paradigm of a general transmitting culture. In Australian cinema this is only achieved with individual films and tv series -fromThe Piano, Babe, or Happy Feet, to Oz imitations like Harlequin and Roadgames or to differing forms of adaptation in Mad Max or Neighbours.These can run the risk of attracting criticism on the home front for 'selling out' Australian specificity.

In a broad cultural senseAustralian cinema might historically be seen to spread at any given time simultaneously across these the five stages. The process is sequential but in essence non- teleological; one stage per seis not culturally superior to another. O'Regan concludes that “the distinctiveness of Australian cinema...must turn on the participation, negotiation, adaptation and hybridization following on from unequal cultural transfers.” see ch.9.

Thanks to the AFI-RMIT Research Library, the most accessible source for otherwise often hard to find original source material.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.