|

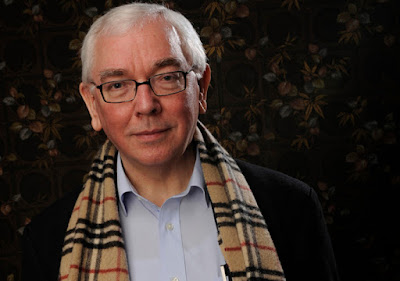

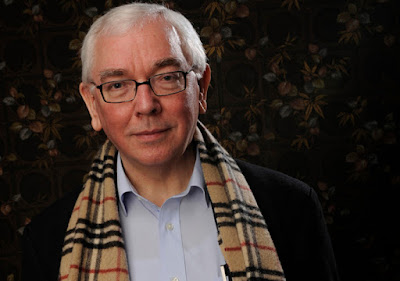

| Terence Davies |

1. In a year of groupthink ― on every side, and at every level―the

antidote could be found in two portraits of extreme individualists, who were

also two of the best-known recluses in American history: Terence Davies' A

Quiet Passion, with Cynthia Nixon all exposed nerves as Emily Dickinson,

and Warren Beatty's Rules Don't Apply, with Beatty tweaking his own

progressive admirers as far-right tycoon Howard Hughes.

|

| Warren Beatty |

From a common-sense

perspective these films couldn't be further apart: A Quiet Passion proposes

that an outwardly tranquil, chaste existence can be as intense and fraught as

any other, while Rules Don't Apply glories in Hughes' reputation as a

seducer to rival Beatty himself. Still, both are reckless acts of imaginative

identification, rooted in the unfashionable notion that the only creed or code

worth having is a personal one.

2. While cinema had a lot of competition this year, most of the larger

spectacle that gripped us all was more depressing than pleasurable. That said,

the continued potency of old-fashioned live TV was demonstrated when a

typically dreary Academy Awards ceremony descended into farce―a moment of

catharsis to delight viewers across the planet, with Beatty, still in the

performance-art mode of Rules Don't Apply, as the instrument if not the

deliberate instigator. “To hell with dreams,” the crucial line from Barry

Jenkins' subsequent acceptance speech for Moonlight, might be the

greatest four words ever spoken at the Oscars.

|

| Donald Trump |

Dominating everything, of course, was the tragicomic reality show Trump

in the White House, supple-mented later in the year by Harvey Weinstein's

appearance in a remake of Beauty and the Beast less sugarcoated than

either Disney version, the pilot of a series destined to run and run. This last

development had nothing and everything to do with cinephilia, forcing attention

to some unpleasant truths about how movies are made and to the question of

exactly what and who might be worth defending. Where Weinstein's downfall is a

blessing on all fronts, I hope we're given the chance to make up our own minds

about I Love You, Daddy―the last we're likely to hear in a while from

the disgraced Louis CK, a major talent whose 2016 web-series Horace and Pete,

an unsparing allegory about the inevitable collapse of patriarchy, now

resonates more than ever.

|

| The Emoji Movie |

3. Hollywood's own collapse is probably still decades away, but

there's no doubt the magic is fading: even the most sophisticated new

blockbusters, like Blade Runner 2049 or The Last Jedi, depend on

spells that lessen in power each time they're cast. For now, most of the

liveliness in American pop culture is on the fringes, in parodies that flaunt

their cynicism and inauthenticity, drawing one way or another from the online

realm which supplies our most plausible glimpses of the future. In this field,

everybody's touchstones will be different: mine include Tony Leondis' dystopian

The Emoji Movie, Joseph Kahn's playfully de-stabilising Taylor Swift

music videos, and Tyler MacIntyre's Marquis de Sade update Tragedy Girls,

a celebration of youthful evil at least as audacious as Bertrand Bonello's Nocturama.

|

| Landscape from Lower Parel |

4. At the Mumbai Film Festival in October, I spend ninety minutes

being ferried across town in heavy traffic and arrive late for CCTV

Landscape From Lower Parel, an “expanded cinema” presentation by the local

artists' collective Camp―part of the festival's The New Medium strand, which also

includes a wide-ranging retrospective of found footage films (or, as curator

and Camp member Shaina Anand prefers to say, simply “footage films”). The venue

for the presentation is a multiplex cinema on the upper level of a shopping

complex in a converted textile mill; Anand and her colleagues take turns

reading from a prepared text about the history of the area, while the screen

shows live images from a remotely controlled security camera mounted on the

roof.

The camera pans and zooms over the surrounding terrain, including the

streets and buildings I glimpsed on the drive over: miming trajectories

described in the text (like the descent of a hot air balloon), singling out

tiny figures on rooftops or in office windows, following birds across the sky.

It's a simple but powerful way of highlighting the omnipresence of surveillance

in the modern city: when an audience member raises concerns about privacy,

Anand points out that each of us would have been filmed by multiple security

cameras on our way into the theatre. It's also the realisation of a seemingly

impossible cinephile dream: that of simultaneously remaining safe in the

theatre and existing inside a movie that comes into being as you watch.

|

| David Lynch |

5. At the risk of indulging in groupthink myself, I can only echo the

testimony of other contributors to this series: Twin Peaks, Twin

Peaks, Twin Peaks. For all the good writing which the long-awaited

third season has already sparked, no critic can hope to illuminate more than a

fraction of David Lynch's unfathomable masterpiece, whether they concentrate on

the elusive big picture or on the sheer strangeness―in conventional terms, the wrongness―of

Lynch's tiniest directorial choices. Almost in passing, the show annihilates all

remaining distinctions between film and television, as well as those between

high and low culture: quite literally, it's both an epic of avant-garde cinema

and a TV soap opera, and almost everything in between.

There is not much I can helpfully add, except that the entire Peaks

saga―three seasons to date, plus the 1992 big-screen prequel Fire Walk With

Me―demands to be viewed as a single, open-ended work. If you're coming to

it fresh, your best bet is to start with the 1990 pilot and keep going right on

through, ignoring whatever you may have heard about the supposed weaknesses of

the second season. Pack provisions, bring a friend, and try to stay ready for

anything. Be warned, though: once you enter these woods, you may not want to

get out.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.